ARTISTS Rhondda Bosworth, Mary-Louise Browne, Margaret Dawson, Kirsty Cameron, Allie Eagle, Jaqueline Fahey, Di Ffrench, Alexis Hunter, Nicola Jackson, Robyn Kahukiwa, Maureen Lander, Vivian Lynn, Lucy Macdonald, Joanna Margaret Paul, Julia Morison, Fiona Pardington, Jude Rae, Pauline Rhodes, Ruth Watson, Christine Webster PERFORMERS Juliet Batten, Margaret Dawson, Lynda Earle, Josie Thomson FILMMAKERS Stephanie Beth, Riwia Brown, Barbara Cairns and Margaret Henley, Kirsty Cameron, Anna Campion, Jane Campion, Nikola Caro, Cushla Dillon, Lynda Earle, Annie Goldson, Fiona Gray, Jessica Hobbs, Shirley Horrocks, Alexis Hunter, Kate Jasonsmith, Chris Kraus, Deirdre MacCartin, Alison Maclean, Shereen Maloney, Nicola Marshall, Merata Mita, Siobhan Oldham, Christine parker, Joanna Margaret Paul, Gaylene Preston, Melanie Reed, Lisa Reihana, Pat Robins, Diana Rowan, Rachel Shearer, Belinda Smaill, Sally Smith, Bronwyn Sprague, Julainne Sumich, Bridget Sutherland, May Trubuhovich, Athina Tsoulis, Vicky Yiannoutsos CURATORS Christina Barton, Deborah Lawler-Dormer FILM CO-CURATOR Deborah Smith PARTNER Auckland City Art Gallery OTHER VENUE Auckland City Art Gallery, 17 December 1993–20 February 1994 PUBLICATION editors Christina Barton, Deborah Lawler-Dormer, texts Christina Barton, Lita Barrie, Deborah Lawler-Dormer, Anna Miles, Cushla Parekowhai, Priscilla Pitts, Deborah Shephard, Bridget Sutherland, Gloria Zelenka

City Gallery reopens in its new space in Civic Square in 1993—New Zealand’s Suffrage Centennial. To mark the occasion, it presents four shows of women artists: Alter/Image, Rosemarie Trockel, Te Whare Puanga, and Jacqueline Fraser’s project He Tohu: The New Zealand Room.

Alter/Image surveys twenty years of work by New Zealand women artists. In the catalogue, curators Tina Barton and Deborah Lawler-Dormer identify subjects and strategies common to feminist art: ‘the recovery of alternate histories and particular experiences, the recognition of the ideological basis of representation, the politics of space and the gender-specific nature of looking, the colonisation of the body and the interactivity of gender, sexuality and identity’.

The project has three components: an exhibition (A Different View: Twenty New Zealand Woman Artists 1973–1993), a film-and-video programme (with thirty-eight artists, from Jane Campion to Lisa Reihana), and a performance programme (with just four artists: Juliet Batten, Josie Thomson, Lynda Earle, and Margaret Dawson).

Feminism asserts the personal as political. Jacqueline Fahey’s 1972 painting Christine in the Pantry—the show’s poster image—portrays a friend swamped by an oppressive abundance of domestic minutiae. Allie Eagle’s work is more explicitly political. There's her shocking right-to-choose protest painting This Woman Died, I Care (1978) and a recreation of her sculpture Risk (1978)—a bowl of red jelly embedded with razor blades.

There are new site-specific installations by Pauline Rhodes, Maureen Lander, and Lucy MacDonald. Rhodes’s Intensum/Extensum combines a gallery sculpture (intensum) with video of a landscape intervention (extensum). In the catalogue, her work is described as ‘perhaps the most abstract example of women artists' desire to make manifest the gendered nature of space’.

The body is key. In her installation Unpacking the Body (1978–93), Joanna Margaret Paul pairs words (including ‘head’, ‘caput’, and ‘cup’) with domestic objects (including a colander), as mementos of the body of her lost baby daughter, Imogen. Rhondda Bosworth’s moody rephotographed family photos also speak of the body, memory, loss. She presents her female subjects in fragments, out of focus, and upside down. The grainy surfaces of photos become analogies for elusive unreliable memories.

Language is the subject of Mary-Louise Browne’s Rape to Ruin (1990), which writes a fallen-woman narrative on a line of eight granite stepping stones. Each stone is engraved with a four-letter word, differing by just one letter from the previous: ‘rape, rope, role … ruin’.

Popular culture and normative representations are interrogated and countered. Alexis Hunter’s six-panel photo-realist painting Object Series (1974–5) ‘reverses the gaze’, eyeing up sexy male subjects—bad boys smouldering in cowboy boots, tattoos, and leather pants, with ripped chests and exposed biceps, their faces cropped out. In one panel, Towers, the figure holds a lit cigarette at crotch height, as the Twin Towers rise up behind him.

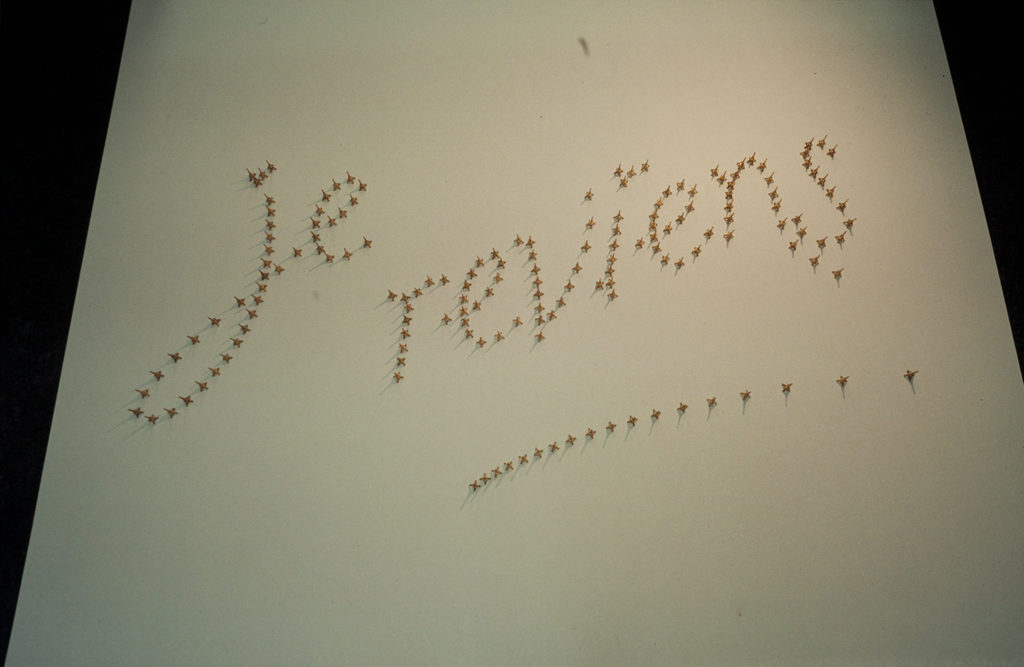

In Souvenir (1993), young artist Ruth Watson also addresses advertising, spelling out the name of a perfume—‘Je Reviens’—using tourist souvenir models of the phallic Eiffel Tower, stuck to the wall. She tells the Herald, ‘I don’t see myself as a feminist artist—feminism has informed my work but I have other concerns’. She isn’t alone. Famously, Et Al. (formerly known as Merylyn Tweedie) declines to be in the show, refusing to be ghettoised as a ‘woman artist’.

Māori artists are also visible. There are three early Robyn Kahukiwa paintings and the film programme includes the first feature film directed by a Māori woman, Merata Mita’s Mauri (1988), and Lisa Reihana’s animated short, Wog Features (1990). But, overall, Alter/Image does little to redress the omission of non-European artists. In the catalogue, the curators admit: ‘In reviewing feminist practice since 1973, we are conscious of the lack of visibility of Māori and Pacific Island women within the debates surrounding feminism, feminist theory, and representation. We hope that this territory may be uncovered and exposed collectively in the near future.’

Juliet Batten's performance The Simultaneous Dress comments on aspects of New Zealand feminist art. Batten designates five zones in the gallery, each containing a text and soundtrack. One at a time, attendees are invited to enter the zones, read the texts, and listen to the soundtracks through headphones. Helpers approach them. One holds out a tray of objects and asks, 'Would you be willing to exchange something of yours for something of mine?' Attendees themselves decide for what constitutes a fair exchange: a pen, a coin, a number, an idea, a poem, or a quotation (possibilities Batten mentions in her instructions). The performance seeks to convey the vitality of the marketplace.

In the Herald, Pat Baskett says the show has a ‘recognisably postmodern thrust’. The show’s word-playing title wears its postmodernism on its sleeve, reflecting a feminist idea about messing with (patriarchal) language. In Art New Zealand, Jane Sayle attacks the show’s ‘generic international style’, suggesting the ‘New Zealandness’ of some works—like Pauline Rhodes landscape interventions—is compromised.

The public programme includes a lecture by visiting professor Sylvere Lotringer. He was then the partner of the well-known author and film maker, Chris Kraus, who is working on her upcoming film Gravity and Grace (1996) and is included in the Alter/Image film program. Lotringer’s talk The Return of Content: Theory and Politics in Contemporary Art looks at critical debate in the 1980s, which argued that ‘market art’ wasn’t political enough.