CURATOR Robert Leonard OTHER VENUES Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, 9 December 2017–4 March 2018; Christchurch Art Gallery, 24 March–22 July 2018; Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, 21 September–4 November 2018 PUBLICATION Publisher Ridinghouse, London; essays Geoff Batchen, Robert Leonard; interview David Campany

British artist John Stezaker is known for his distinctive, often deceptively simple, collages. He has been making art since the 1970s, but achieved prominence relatively recently. In 2011, he had a retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, and, in 2012, he won the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, even though he does not take photographs.

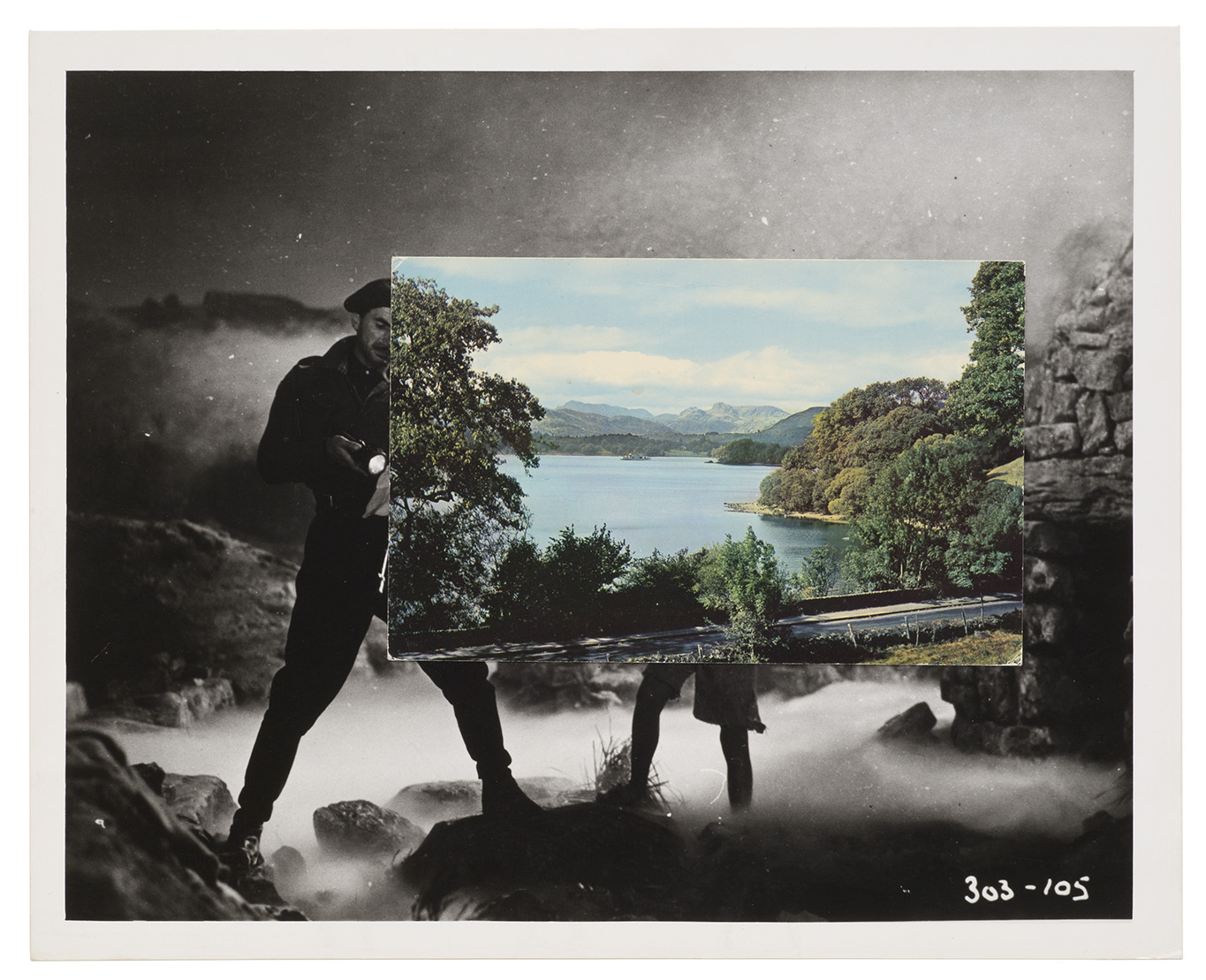

Stezaker says collage is about ‘stuff that has lost its immediate relationship with the world’ and involves ‘a yearning for a lost world’. A collector, he works from an archive of out-of-date images—mostly old film stills, vintage actor head shots, and antique postcards. These images come in standard sizes and are highly conventionalised—all variations on themes. Critic David Campany says, Stezaker ‘is drawn to that very slim space between convention and idiosyncrasy.’

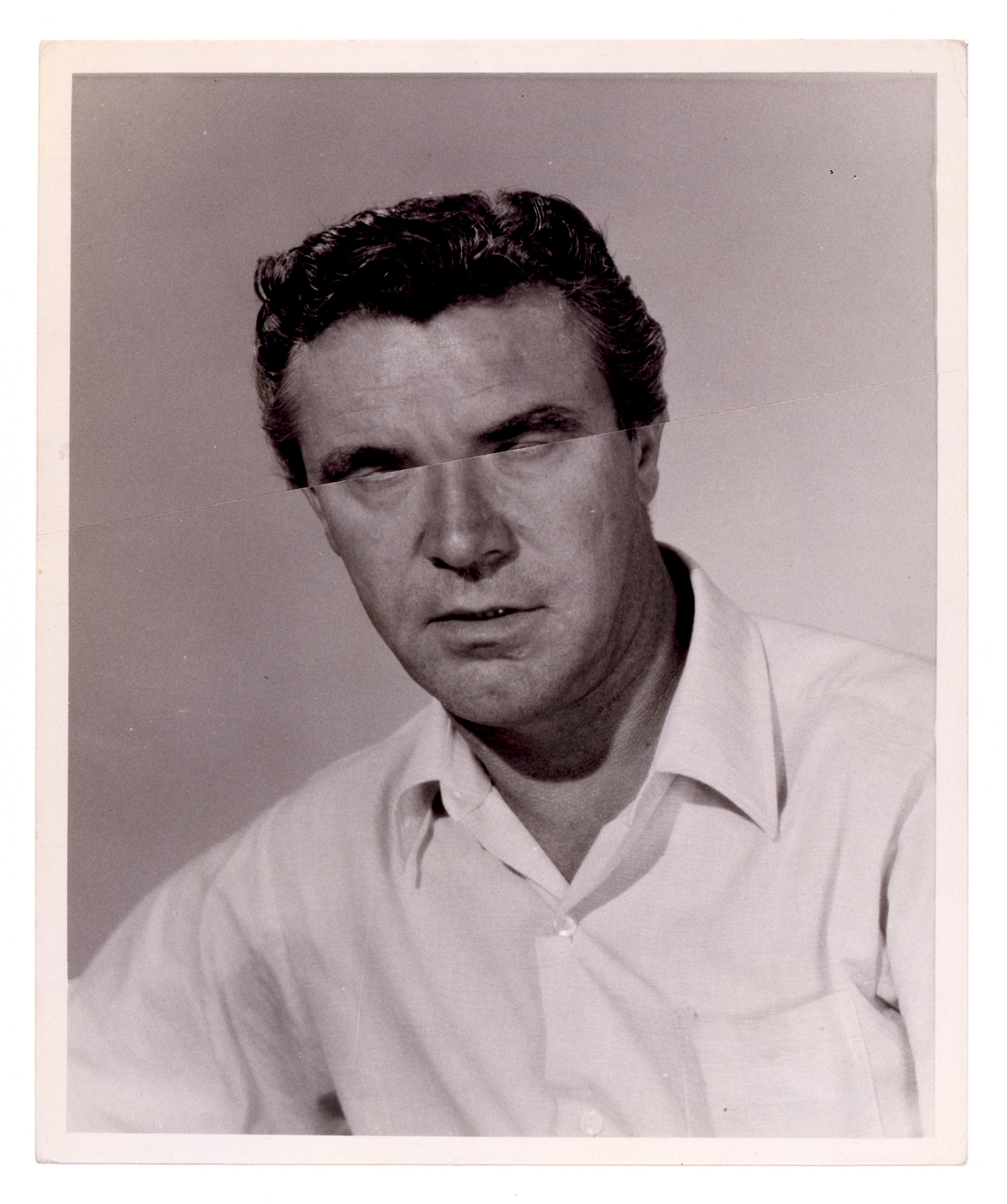

Collage involves taking existing images and materials, decontextualising them, reorienting them, cutting them, pasting them. But Stezaker’s collages often only do one or two of these things. Sometimes he cuts and pastes, sometimes just cuts or just pastes. Indeed, sometimes he just selects, presenting a found image more or less as is. (He calls such 'collages' readymades, as a nod to Marcel Duchamp.) Highlighting the different contributions these distinct processes can make, Stezaker foregrounds the grammar and logic of collage.

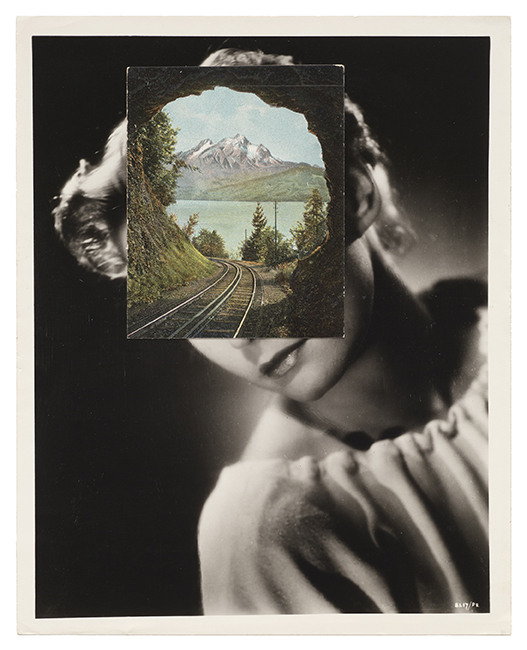

In this time of Photoshop, which makes melding images a breeze, Stezaker prefers to make collages the old way, working with his source materials as is, exploiting the ways they fit and don’t fit together. In his Masks, he lays scenic postcards on top of head shots so that the forms line up, uncannily—we want to read them as one. He makes rock faces, wave faces, arched-bridge faces, and buildings-with-windows faces. In his Marriages and Betrayals, he grafts head shots together, creating more-or-less convincing gender-and genre-blending hybrids. Faces wear other faces, as masks.

Stezaker conjures with seeing and blindness, the visible and invisible, presence and absence. He slices strips off film stills, recalibrating and reorienting the drama. Sometimes he cuts out shapes from stills, directing our attention both to what has been removed and what remains. In some works, he cuts the figures out of stills and lays these stills over other stills where the figures remain, catching figures and figure-shaped absences in a dance. It’s all very René Magritte.

Stezaker's source images come from a pre-feminist age, when men were men and women were women, when gender was more defined and constrained—especially in the movies. Stezaker both revels in and queers stereotypes, making them dance to his own tune.

In addition to collages, Lost World includes poignant found-object-sculptures: a selection of antique mannequin hands, offering a repertoire of gestures. There’s also a video, Crowd, presenting hundreds of film stills of crowd scenes, each for one frame only, in a bewildering melange.