Chief Curator Robert Leonard talks with legendary branding and communications expert Howard Greive on marketing things to New Zealand and New Zealand to the world.

During the halcyon years at Saatchi & Saatchi Wellington, Greive worked on iconic campaigns for Telecom and Toyota. In 2002, with Peter Cullinane and fellow Saatchis defectors Kim Thorp and James Hall, he founded the communications agency Assignment, whose clients included Tourism New Zealand. In 2003, with Simon Woolley, Cullinane, and Thorp, he founded Antipodes, to produce premium bottled water. An art-world insider, he was on the organising team for Et Al.’s controversial 2005 Venice Biennale project.

Robert Leonard: You must have worked on a lot of national-branding projects.

Howard Greive: A lot that never saw the light of day. A long time ago, Saatchi & Saatchi and Colenso were brought together to try to find a unifying brand story for New Zealand and we came up with New Zealand Fresh: ‘fresh thinking’, ‘fresh food and wine’, ‘a fresh place to holiday’, all that. It never got anywhere. New Zealand governments are always trying to find a unifying brand that works for everything, for tourism, trade, sport, etcetera. The search for a defining symbol is perpetual. It was the impulse underlying the flag debate two years ago. The National Government wanted to find a symbol to represent us everywhere, hopefully the silver fern.

Because no one wants to put the Union Jack on a New Zealand–made product?

Exactly. My problem always was, if a flag is a brand or a logo, then you would treat it like any other brand or logo. Over time you would refine it, refresh it; you would keep it contemporary, not totally reinvent it. Take the Coca-Cola logo. For over 100 years, it’s been continually redrawn to keep it contemporary. But, it’s still red with flowing script. When the Government confused the flag with a national logo, things got messy, then they got political. When everyone started loving Fire the Lazar!, you knew the Government was on a hiding to nothing.

The flag debate asked New Zealanders about their view of themselves. But, there’s a big difference between branding New Zealand to New Zealanders and branding it to others.

Definitely. As a nation we’ve got better at understanding that it’s not about us; it’s about what our audience wants to think about us. 100% Pure was the result of Tourism New Zealand research that showed that the thing other people love about New Zealand is its natural beauty. That’s what they come for. So we use beautiful images of mountains, lakes, beaches, etcetera. (There are occasionally people in there, for scale mostly.)

With brands, you’ve got to own one thing—a single-minded proposition—and sell that. Before 100% Pure, it was woeful. Tourism New Zealand had offices around the world. They were each given a budget and would go find their own agency, and each agency would advise something different. It resulted in a fractured image of New Zealand. When George Hickton came to Tourism New Zealand, he brought things back to New Zealand, shut a bunch of those offshore offices, and put the money into marketing. He knew it’d be more economical and powerful to have one message and spread it throughout the world.

Assignment didn’t come up with the 100% Pure brand. When we won the account, the brand was already in place. They said, ‘Congratulations, you’re working on this, but don’t change it.’ Our job was just to refresh it. We did that by coming at New Zealand as the youngest country on earth, the last land mass to be discovered, which is an interesting way of looking at it.

There’s been criticism of 100% Pure. But the criticism doesn’t understand what a brand does. It takes it literally, rather than see it aspirationally or promotionally.

100% Pure is an advertising line. It’s got this flexibility, because it can be used in various ways—like 100% Pure excitement, 100% Pure relaxation—which is the brilliance of it. The crazy thing is, people shouldn’t even see it here; it’s designed for overseas consumption. But, when it got back here and got co-opted into a local debate over river pollution, its real power was revealed. But I like that the debate keeps the acid on our behaviours. A product and its advertising do have to be in sync; dissonance becomes a problem.

Will 100% Pure survive?

I think it will. You have to own a brand and you have to live up to it. It’s dangerous to walk away from an established proposition. In advertising, the client and the agency get sick of things long before the consumers do. You’ve seen it a zillion times and you’re bored of it, but the consumers are only seeing it every now and then. 100% Pure has legs.

Can one message work for every audience?

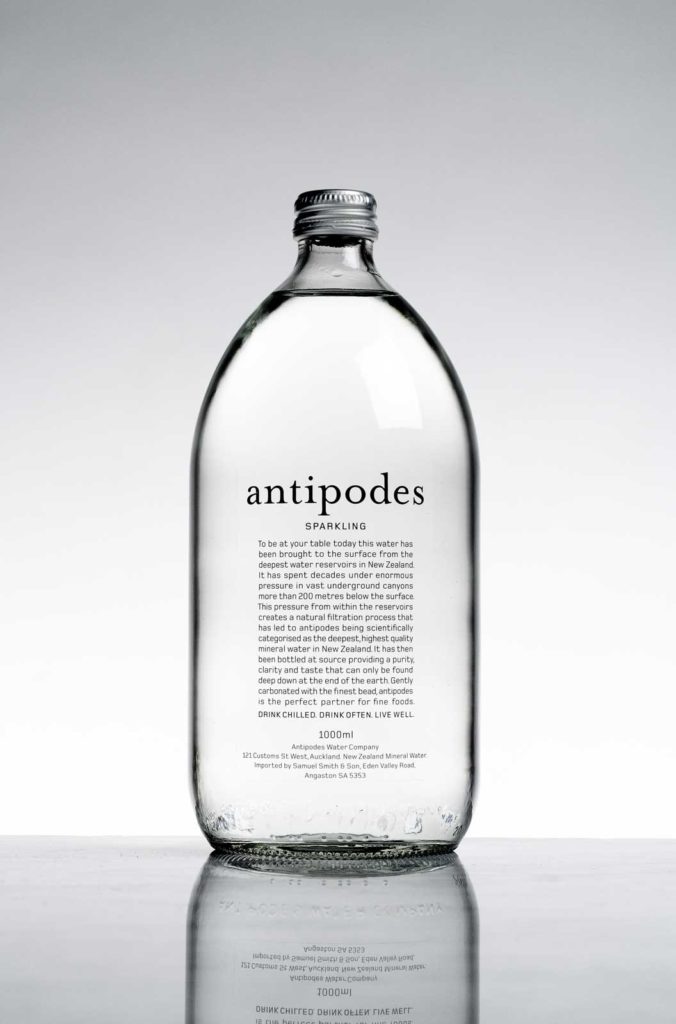

Sure. International brands are powerful because they stick to one image or proposition. But it’s hard to achieve. Take a look at New Zealand products sold into China. The branding gets messy. We’re guilty of this too, with Antipodes water. Our label looks okay but not great, mostly because it’s in Chinese. Whereas, premium brands—which a lot of New Zealand brands should be—should be strong enough to be in English or French or whatever. The consistent imagery and tone will resonate. Hopefully, with Antipodes, as with Coca-Cola, people will eventually recognise the aesthetic, the bottle shape, and the letter forms, and know what it is. They’ll get there.

You’ve also worked on New Zealand Story.

I’ve done a bit of work on it. It’s not a logo; it’s a smart toolbox. When an exporter opens it up, they’ll find images of New Zealand. If you’re a water exporter, like we are, you might want to use these images of beautiful natural scenes in your own promotions. And, if you’re a manufacturer, there’s shots of high-tech manufacturing. Within the toolbox are backstories to put context around whatever you’re exporting.

How did Antipodes happen?

We founded the company in 2003. Our partner Simon Woolley, a famous Auckland restaurateur, was in New York for years. When he came back, New Zealand had changed. We’d won the America’s Cup, and were hosting the challenge. He sensed a new beginning for the country. But, he went to restaurants and found everyone was drinking Perrier. He said, ‘We should have our own premium water. Our water is better than their water.’

Isn’t water just H2O the world over?

No. In fact, all water has its own fingerprint, derived from its own environment. You’re not going to drink Chernobyl water, are you?

Chernobyl water may have no bugs in it.

It may have zero bugs or it may have extremely interesting bugs.

The Antipodes bottle is distinctive. How did you decide on it?

We were immediately drawn to it because it was so different. Amongst a sea of potential ‘flash’ bottles, it stood out. In the beginning, we had to import the bottles, but we make them here now, using recycled glass. We take our commitment to the environment seriously. Antipodes is the only bottled water in the world which is carbon neutral to any table in the world. Our overseas competitors don’t do that.

Now, the Government wants to charge you for the water.

The whole debate about charging bottlers for water usage is, I believe, a reaction to overseas companies, mostly Chinese, buying water rights in New Zealand and shipping water in bulk in plastic and not paying for the usage. They treat it as a commodity, rather than as something special. However, if you look at it through the Antipodes brand, seven bottles out of ten that we produce are exported, and they sit in the finest restaurants all around the world as a shining example of New Zealand. It’s beautiful water—it’s been judged the best in the world—in a beautiful bottle. If we had to pay a tax, naturally we would, but what the politicians have to realise is that our biggest competitor internationally is San Pellegrino, which is so much bigger than us. It’s owned by Nestlé, who think they should own water rights everywhere.

However, the Government can’t tax water imports because that’s breaking international trade rules. So, Antipodes would be seriously disadvantaged by a tax. We’re expensive anyway, partly because we’re paying carbon credits, and then we’re going to be even more expensive than our biggest competitor, who can Goliath us.

You mentioned Colenso earlier. In the 1980s, Colenso’s Len Potts pioneered New Zealandness in advertising. What did you think of his work?

Fantastic. Colenso were the first to realise that there’s a distinctive New Zealand voice or accent you could bring to brands. Before them, branding was done according to the Ogilvy and Mather bible, with posh voices and no native humour. Colenso cracked it and it just went off. Potts kept it alive for a long time, but, like all styles of art or advertising, it got tired; it ran its course. At Saatchis, we started doing sharper, idea-based ads that didn’t lean so heavily on nostalgia and jingoism, but still had vernacular references, like the Spot the Dog ads for Telecom (1991–8) and the Bugger ad for Toyota Hilux (1999). For us, the idea was sacrosanct. To win awards, ads had to play to international juries, who get good ideas. We started to win a lot of awards.

Your ads had more irony. In Potts’s Sailing Away ad (1986), there’s zero irony.

None. I don’t think there’s a great idea in Sailing Away either. It’s just this emotional bomb. The Colenso ads were heartfelt and I loved them. But ours had irony, a little wink, and ‘fuck, it’s only advertising’.

Last century, there was a New Zealand audience. You could buy time on TV to promote things and everyone would see your ads. Now we’ve got streaming; everything is narrowcasting and niche. The idea of a national audience seems to have disappeared.

I don’t think that’s true. We’re only four-and-a-half-million people, so you can’t niche New Zealand. America is made for niche. You’ve got a huge market and huge variation within that market. You’ve got Puerto Ricans, you’ve got African Americans, etcetera. You can find the media channels they’re listening to and make ads to talk to them. But, in New Zealand, the money is always in the middle, not on the fringes. The Internet is soaking up advertising dollars, but it has had little impact on the amounts spent on television.

So, here, small size generates identity. Whereas in a bigger country, like America …

It doesn’t. We’re huddled together …

… on KZ7.

Yeah, we’re all there together on KZ7. You can talk to us because we’re easy to reach. TV remains the best medium. Two reasons: sound-and-vision is a dangerously good cocktail and everyone watches at the same time—news, All Black tests, America’s Cup, etcetera. There’s something powerful about people getting the same message at once. If it’s a great ad, they’re talking about it around the water cooler the next day. The nation is receiving this stuff.

One of our biggest national-identity projects has been Te Papa. Saatchis crossed paths with Te Papa on several occasions early on. In 1992, during the architectural design process, you all came up with an alternative idea for the building—a big paua shell. Was it a serious suggestion, was it about shifting the debate, or was it profiling Saatchis as a voice in the culture?

All the above. What they had picked was disappointing, no doubt about it, and they knew it. It was just a box with adornments. We came up with the paua-shell idea to provoke them to change it. We took the illustration to the Evening Post, who ran it on the front page. Gavin Bradley and I got taken to the architects’ office. They were concerned and tried to appease us, to ‘capture us’, as they say in politics. But, fundamentally, the brief was wrong. If you’re writing an architectural brief for a new national museum, it should not be easy; it should be a challenge. It should challenge the architects with inspiring objectives. It should challenge the engineers and builders to realise it. Ultimately, it should challenge everyone to see New Zealand in a whole new light, as opposed to being easy, which we love in New Zealand.

Later, Saatchis were engaged to design Te Papa’s logo. I love that scene in the documentary Getting to Our Place (1999), where Saatchis is pitching a logo design to this miserable, grim-faced board. It seems like a war: agency enthusiasm versus client negativity.

If it was hard then, imagine how hard it would be now to get a logo for your national museum. All these committees doing research. You’d never get there, I reckon.

What was your involvement in the et al. project in Venice in 2005?

I was and remain a huge et al. fan. The commissioner Gregory Burke asked me to join the team, to help with communications and marketing. It was a small team. There was Greg, myself, and Creative New Zealand (CNZ) had a couple of people. Dayle Mace was brilliant at organising the patrons and

we had John McCormack and Jim Barr and Mary Barr helping out where they could. But a shit storm hit and almost derailed the whole thing.

What happened?

It started with the CNZ media release, announcing et al. as New Zealand’s artist for Venice. I argued that we were making a rod for our back with that release. When you’re dealing with art media, that’s fine. They understand the idea of ‘et al.’. But when it’s the general media, and it’s taxpayers’ money, they go, ‘Who’s et al.?’, and, if you don’t explain, they’re going to keep digging and digging until they find out. Then, in the process, they find that the artist won’t talk to the media. So, they hound her; they camp outside her house. I thought we should have explained from the outset that et al. is a pseudonym for the artist Merylyn Tweedie, and get that out of the way. But I lost that one, and, before you know it, it’s on national TV for weeks, with a highly agitated government. I felt sorry for Peter Biggs, chair of CNZ. He did a fantastic job fronting the project on the Paul Holmes show, but he was chucked under the bus basically. I always remember the arts programme Front Seat. I thought, if one show is going to come out in support it’ll be the arts programme. But no, they just covered the story from a slightly different angle. Thank god Robert Storr gave et al. the Walters Prize. If we’d lost that, we would have been well fucked. But that stopped a lot of it.

How did it play in Venice?

Great. It was a sharp work from et al. And I think we did a brilliant job of looking at how to market an artist in Venice. Before, half the marketing money would get soaked up in an Artforum ad, which was lazy thinking and largely ineffective. We decided that the whole thing was about key influencers and the best thing was to spend the money on trying to get them to see the work. Greg, to his credit, went off around the world—because he’s got kahunas—and started door knocking, talking up the show. We lined up all the key people to see it, knowing they would spread the word. That was smarter than buying an ad.

The other thing was the opening party. It was the hot ticket. I thought it would be brilliant if New Zealand become famous for its party. There are eighty-five countries trying to get instant awareness in the three days of the vernissage. When you’re small, you do whatever you can for attention. So, the art is sort of like, ‘ah, whatever’, but ‘shit, New Zealand throws a party’. People were talking about it. The young artists, who typically hate the opening parties, said ‘You’ve got to go to the New Zealand party.’ We had tons of them invading. We got 42 Below to come in as a sponsor. Geoff Ross shipped over a lot of vodka and mixes, their best mixologist, and these wacky, brilliant ads. I met with the mixologist an hour or two before the party. He said, ‘What shape do you want this thing to take? We can create drinks so it goes like this [Greive draws a series of waves] or you can have ones that go like this [he draws a rocket climbing in a straight line].’ ‘Yeah’, I said, ‘I want that.’ We were only going to get people for two hours and I wanted them to be well oiled when they left. You know, those old matrons the patrons, everyone, they were smashed and loved it.

With its national pavilions, Venice is quite old fashioned. Countries can fund a show, make it, send it. It’s not some curator from somewhere else picking the artist they want and asking us to pay for it. That’s why it engages our art scene like nothing else—we have agency. There’s a good side to public debate around who to send—people are talking about art. But, it creates a problem. Since et al., there’s an anxiety that you need buy in from the home audience, rather than simply target the narrow art-world audience that actually goes to Venice and go for broke.

We’re back to the 100% Pure problem. Venice is about selling to the offshore audience, not about selling back into New Zealand. When you’ve got to satisfy two masters, that’s where you start getting difficulties. How many successful ones have there been?

They’ve all been successful in different ways …

Really? So, why do we send art to Venice? Why do we do that? What’s the reason?

People buy into the ‘Olympics of art’ rhetoric. They think we’re going to win the Golden Lion and then they can say New Zealand ‘punches above its weight’. That’s a mistake. Venice tests our mettle; it raises the stakes. Succeed or fail, we learn a lot from just being there. It makes our art tougher, better. But that’s a hard sell.

I understand when you say it’s enough just to be there, to be part of the international discourse on art and culture, because it makes us better. But, if I had to justify going to Venice, I’d say that we’re trying to open up new dimensions to New Zealand’s image. People see us there and think, ‘New Zealand, you do amazing contemporary art.’ Behind that single thought lies a huge subtext—a deeper commitment to creativity, design, innovation, and, yes, branding.

–

Originally published in the catalogue for This Is New Zealand.