Kirsty Baker

Site Seeing brings together the work of contemporary Māori photographic artists Conor Clarke (Ngāi Tahu, Scottish, Welsh) and Bridget Reweti (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi), encouraging us to reconsider the ways we see the land and how we might imagine our relationships to it. It is an exhibition concerned with the ways that we picture place. It is concerned, too, with the myriad ways that we might experience place, beyond the frame of a carefully composed photograph.

To make a journey is to create a connection, to trace a pathway between one place and another. The land is layered with these pathways, spanning geographies and temporalities, connecting people to place. Tar-sealed highways stretch along coasts and through valleys, allowing us to rapidly cover ground that would once have been traversed by foot. The skies above us are latticed with pathways too, the invisible flyways of migratory birds as they navigate from one side of the globe to another. The connective power of journeying—of moving through the land, water, or air with attuned care and attention—can be seen across both Clarke and Reweti’s practices. Their work draws our attention to the connectivity of place, to the journeys that connect people to each other, and the ways that we—as humans—are intrinsically enmeshed with the more-than-human. Their work draws our attention to whakapapa as lived ontology.

Hanahiva Rose (Te Atiawa, Ngāi Tahu, Ra’iātea, Huahine), discussing the role of whakapapa as a framework for her curatorial and research practices, explains that ‘Whakapapa, as a verb, is the action of placing in layers. It is from these layers of connection—both known and unknown—that the world takes shape. Seen in this way, whakapapa extends beyond the lines of descent which we, in English associate with its common translation as “genealogy”, to represent a connection to landscapes and ecologies; a source of knowledge and relationship; the transmission of stories and histories; an obligation to past, present, and future.’i Each of these elements is markedly present in the work of Clarke and Reweti. Through their expansive exploration of their medium, they each consider photography’s potential to enliven those layers of connection embedded in the places they picture. In Site Seeing, Clarke and Reweti offer Māori ways of seeing site, taking viewers on a journey traversing landscapes and ecologies, knowledge and relationships, stories and histories, past, present and future.

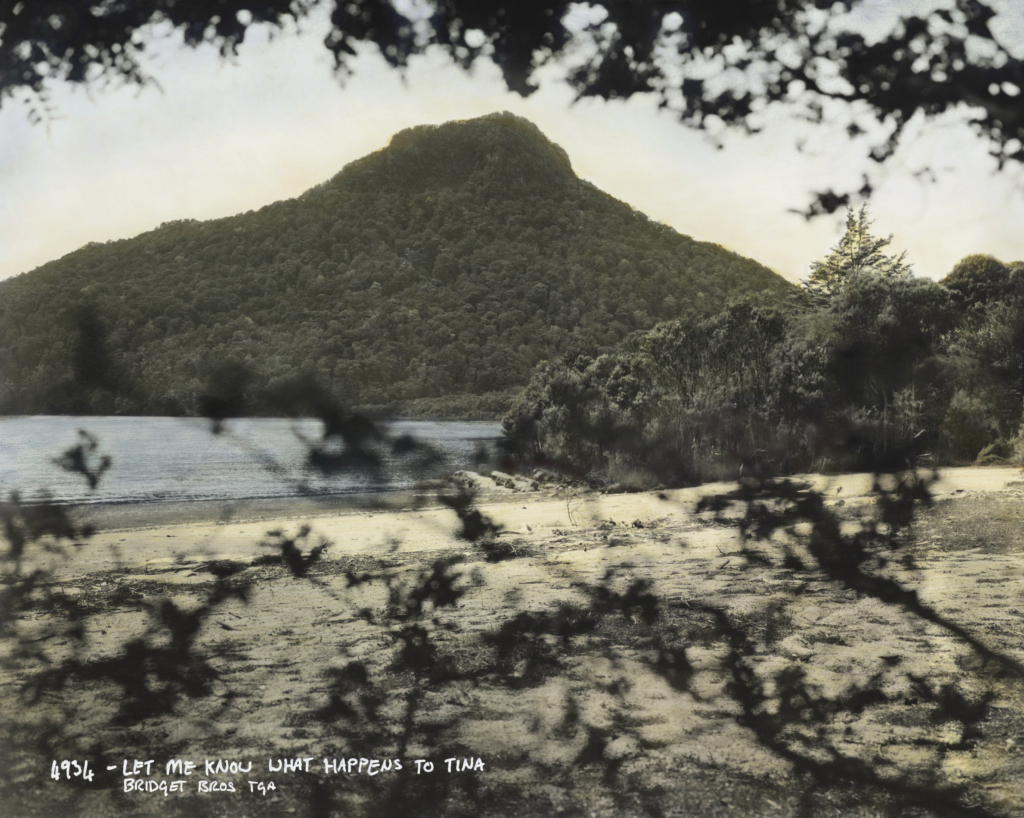

While many of the works included in Site Seeing gesture towards these themes in broad terms, there are several works which refer specifically to the act of journeying. One of these, Reweti’s 2021 series Summering on Lakes Te Anau and Manapōuri centres around the re-creation of a historic journey undertaken by one of colonial New Zealand’s most widely known photographers. Made during Reweti’s 2020 / 2021 Frances Hodgkins’ residency, this body of work grew out of archival research into Alfred Burton’s photographic series Wintering in Lakes Te Anau and Manapouri. Burton’s series documented a commercial photographic journey around the area and was published in serial form in the Otago Daily Times. The Burton Brothers Studio of Dunedin, operated by Alfred and his brother Walter, is perhaps the most widely known of the numerous photographic studios established in colonial New Zealand. Collectively, the photographers working in these studios produced a wealth of landscape imagery which has come to hold a pervasive power within the collective visual consciousness. As Dr Nina Tonga (Vaini and Kolofo’ou, Kingdom of Tonga) notes of the scenic images in Wintering in Lakes Te Anau and Manapouri, ‘many of Burton’s “composed” photographs helped to construct the image and identity of Lakes Te Anau and Manapouri as a tourist destination.’ii

Taking Burton’s photographs as her starting point, Reweti embarked on a trip with friends and whānau, setting out to recreate as many of the composed landscapes as she could identify. However, as Reweti reminds us, ‘Māori time is aspherical. Starting at the centre and moving in any direction and this ability to be able to reach into the past or future might sound confusing but is actually really grounding. It provides a knowledge of being part of a continuum that is far bigger than our individual selves.’iii From this understanding, it becomes clear that Reweti’s journey around Te Anau and Manapōuri is not a contemporary reworking of a historical series, rather it offers a richly experiential encounter with place that can be layered into a continuum of image-making.

Reweti’s connection to the rohe she travelled around stretches through her whakapapa to her tipuna Tamatea, a navigator and explorer renowned for his journeys around the moana and whenua of Aotearoa. Known by many names, including Tamatea Pōkai Moana (ocean explorer) and Tamatea Pōkai Whenua (land explorer), his name and legendary journeys remain alive in numerous placenames across Aotearoa. Reweti, a descendant of Tamatea, layers her journey around the rohe into this whakapapa, through the creation of Summering on Lakes Te Anau and Manapōuri. Like Burton before her, Reweti used large plate negatives to produce silver gelatin prints. Unlike Burton, however, Reweti sought to integrate the physical materiality of place into her images, enlivening them beyond the realm of the purely visual. Using whenua—earth—gifted from Ōraka Aparima mana whenua, and with permission to use it in this way, Reweti hand coloured the photographic prints with whenua pigments. Through this act of layering whenua upon the image of whenua, Reweti expands the parameters of the photographic print beyond the purely visual.

The politics of vision have been deeply codified within Western culture. Donna Haraway, writing in her seminal essay ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,’ outlines the dominant power dynamics of looking that we have come, increasingly, to understand as shaping the ways power is encoded in the world. ‘The eyes have been used to signify a perverse capacity—honed to perfection in the history of science tied to militarism, capitalism, colonialism, and male supremacy—to distance the knowing subject from everybody and everything in the interests of unfettered power.’iv When it comes to looking at the land, Colonial-era landscape photography has played a key role in perpetuating the myth of this distancing mode of all-consuming vision. Such photographic landscapes emphasise the separation of viewer and land, transforming place into something that can be composed, commodified and consumed. In contrast to this, Reweti’s journey through Te Anau and Manapōuri works to trace the land back upon the landscape by emphasising the physicality of the whenua and the whakapapa connections it holds within it. Summering in Lakes Te Anau and Manapōuri extend the act of seeing beyond the purely visual.

Conor Clarke’s photographic practice has long been concerned with the ways vision has shaped our perception of nature, particularly as this relationship has been mediated by the camera’s lens. In her series Scenic Potential, Clarke emphasises the camera’s role in constructing culturally specific understandings of natural beauty and splendour. Initially appearing to depict dramatically craggy mountain ranges, images such as Landscape I, Berlin (2014) rapidly betray their own artifice. What at first strikes us as a scene composed of receding peaks and summits reveals itself as something entirely different. The distinctive tread marks of heavy machinery that cut into the foreground collapse the scale of these peaks, shrinking them from the stuff of scenic grandeur to that of urban construction. To make these images, Clarke photographed piles of dirt and sand before digitally manipulating them to conform to compositional norms established in eighteenth century England.v We are so accustomed to seeing a particular formulation of scenic beauty in the jagged summit line of a mountain range, that our vision unconsciously resolves these piles of dirt into such a scene.

Mountains are a familiar motif in Clarke’s photography. Often, though, they are depicted in ways that make viewers acutely aware of the mediated nature of vision. In Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear, for example, the mechanics of looking are made literally visible. We look down at the viewfinder of Clarke’s medium format camera, the body of the camera itself providing a heavy black frame for the mountain she pictures. The viewfinder is latticed with a grid of horizontal and vertical lines, dividing vision into easily quantifiable compositional units. This geometric lattice is pictured in sharp focus, the mountain captured in its grid blurred and indistinct in comparison. Here the camera becomes a tool for seeing, but also a tool for obscuring vision. Confronted with this process of a photograph’s construction it is impossible to ignore the extent to which the camera mediates visual experience.

The grid imposes a rigid logic onto the act of looking at, and understanding, the land. Like the trig point and the imperial surveyor’s chain—both of which are visible in Site Seeing—the grid, as a unit of measurement, works to rationalise and contain the land. In combination, these measuring tools have enabled and perpetuated ways of seeing site that have allowed land to be measured, divided and tamed—to be transformed into a saleable commodity. In Clarke’s A mountain reveals a mountain we are presented with a very different way of looking and understanding the land, one predicated on relationality, rather than commodification. The image itself is visually simple, depicting a closely cropped section of intertidal sand upon which a small mound has been created. Handprints can be traced across its surface, the distinctive indentations of finger-marks pushed into the tightly compressed wet sand. Along the photograph’s upper edge we catch a glimpse of foamy water as the tidal pull drags a small wave back towards the ocean. Here, as in Landscape I, Berlin, is a mound of sand, constructed into the shape of a mountain. Unlike that earlier image, however, this photograph is deeply imbued with the specificities of the place in which it was made. Clarke’s Ngāi Tahu whakapapa connects her to Mangāmāunu, just north of Kaikōura township, and to Tapuae o Uenuku, the highest peak in Kā Whata Tū o Rakihouia the Kaikōura ranges. This mountain—her ancestor—is visible from the beaches on the southern coast of Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, where A mountain reveals a mountain was created.

Clarke outlines the geological journeys that connect the site of the photograph’s creation with that of its origin: ‘From a birds-eye-view high above Kaikōura, the Seaward and Inland Ranges can be seen running parallel with one another, with the Waiau Toa (Clarence River) flowing between them. The river carries with it pieces of eroded rock that become sand as they flow out to sea through the vast underwater canyon, before drifting with the ocean current up the coast, to be distributed on beaches around Te Whanganui a Tara (Wellington). It is here, while staying with friends nearby that I gather and shape a small mountain. Here and there cannot be seen in isolation…’vi The rivers and seas which separate the landforms of Te Waipounamu and Te Ika-a-Māui also connect them: here and there always exist in relation.

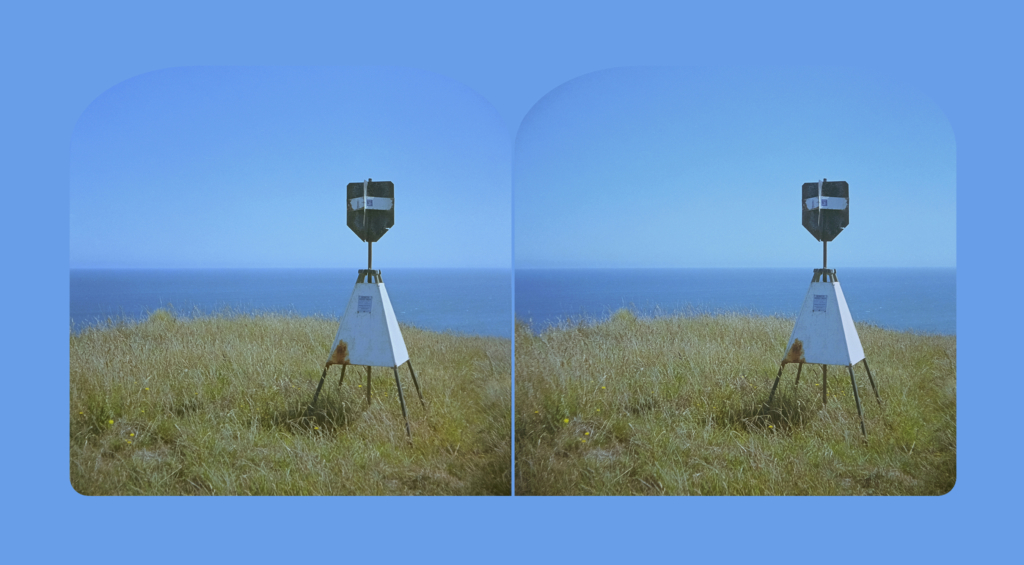

This assertion of the relationality of place—the understanding that here and there cannot be seen in isolation—underpins Reweti’s photographic series, How to drain a swamp. The full series consists of 21 stereoscopic photographs, each depicting a trig beacon situated on a peak around Te Awa Ōtākou Otago Harbour. To create a stereoscopic image, two almost identical photographs are placed side by side and are then viewed through stereoscopic lenses to create the illusion of three-dimensional depth of field. The photographs that make up How to drain a swamp are arranged in sets of three, each set named in te reo Māori for a single peak: Hereweka, Kāpukataumāhaka, Ōtāne, Pikiwhara, Te Rotopāteke, Tūtaehinu and Whakaohorahi. By doubling and then tripling images taken from these sites, Reweti places multiplicity at the heart of her depiction of place. None of these maunga exist in isolation but, rather, in constant relation. For a viewer with knowledge of this landscape, these images visually map the lines of sight that connect these peaks into a network, bringing here to there into direct relation. For those who are familiar with the ridgelines and gullies, the inlets and summits depicted beyond the trig points, these paired images offer visual fragments of an experiential understanding of place. For those of us who are not familiar with the terrain—nor the names by which these peaks are known—How to drain a swamp gives us something quite different. It shows us that knowledge is not always accessible by sight—is the ridgeline we see in the background of Hereweka 1 one of the other peaks in the series? Where would you need to stand to see the uninterrupted horizon line of ocean meeting sky in Ōtāne 2? This is knowledge gained by spending time in a place, coming to know its geography and its history, coming to know the stories held within its placenames. For a viewer who is connected to this place, How to drain a swamp traces a network of vision and connection, piecing together an understanding of Wai Ōtākou that is multiplicitous, abundant and cumulative. These photographs emphasise a form of looking that acknowledges the knowledge systems embedded within the land, rather than standing outside of it. Contrary to colonial logic, to simply see a place does not mean to know it.

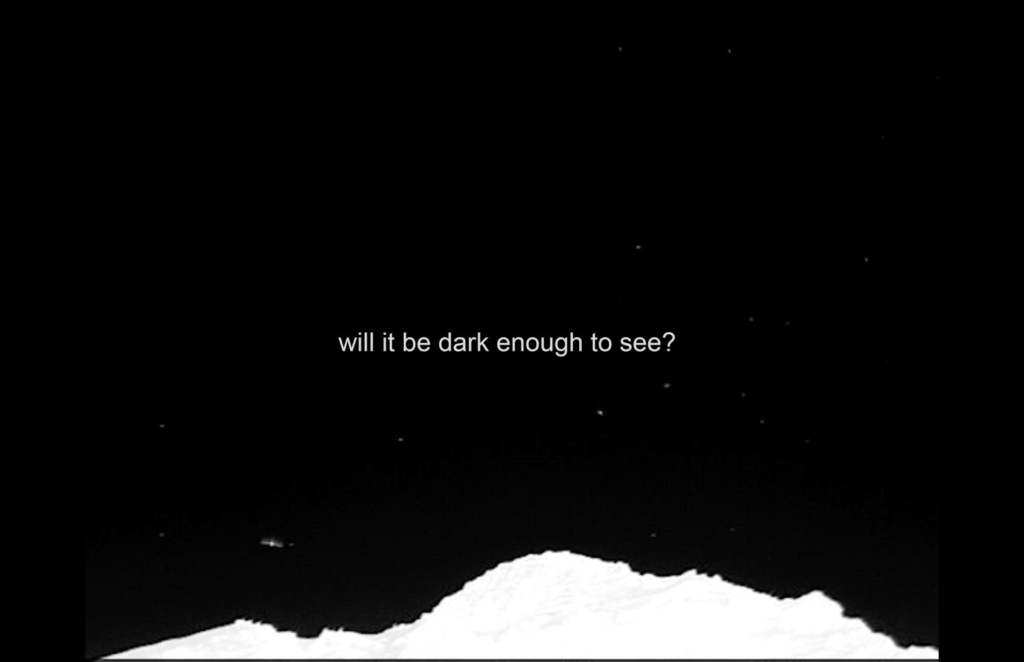

The idea of experiencing place in ways that transcend the purely visual has been a central concern within Conor Clarke’s recent artistic practice. As she asks, ‘is seeing with the eyes to truly know a place, a mountain, an ancestor? What does ocular vision have to do with knowing, being, or belonging to this place?’vii In Night writing and Follow your nose Clarke experiments with the translation of vision, mapping journeys which have largely remained invisible to the human eye. These films, alongside Reweti’s Summering on Lakes Te Anau and Manapouri, offer the most direct representations of journeying in Site Seeing. Clarke’s films trace open a window into the night sky, using thermal imaging technology to map the heat held in the bodies of Kaikōura tītī as they make the return journey from their alpine nesting environment out to the ocean to feed. Clarke, reflecting on the anomalous nature of the Kaikōura tītī, the only seabird to nest in an alpine environment, considers the role the mutability of geography may have played in this. ‘With a whakapapa (layered genealogy) stretching millions of years, the Kaikōura tītī are an ancient species—and the mountains some of the world’s youngest and fastest growing—making it possible the ancestors of these tītī burrowed into cliffs that grew into mountains. Have these mountains risen up from the coast, carrying the tītī with them?’

These films capture and isolate a single fragment of the journeys undertaken by these tītī as they trace their flight paths above Clarke, who remained stationary on the earth below. As their body heat is translated into a constellation of motion, the swoop and soar of their bodies fills the image as they cross, briefly, through its frame. These films offer us a multitude of questions, asking us to consider what we may be able to discern if we paid attuned attention to these flight paths; to this night writing. What knowledge systems might be embedded in such journeys, and how are we, as human viewers, entangled—or implicated—within them?

Site Seeing at National Library of New Zealand | 12 April – 2 August 2025