.

Our friend, Auckland artist Peter Roche, died in July. It was cancer. He was sixty-three. Roche started out as a performance artist in the mid-1970s, creating edgy works, often involving self harm. He ravished himself with razors, administered enemas, and had sheep kidneys sewn to his back. These early works tested his audience’s limits as well as his own. In the late-late 1970s and early 1980s, he and partner Linda Buis created performances exploring their ‘relation’ in time and space. In the mid-1980s, Roche began creating kinetic sculptures with menacing, masculine, militaristic overtones, with machines becoming stand-ins for human actors. In the late 1990s, he acquired the cavernous, dilapidated Ambassador Theatre in Auckland’s Point Chevalier. Returning it to its former glory, he developed it as studio and residence, and, until 2011, he ran a bar and rock-music venue in the front. Out back, the studio became an ever-changing installation, which he occasionally opened to visitors. Roche increasingly focused on creating light sculptures, including his dramatic installation Conduit (1998), a Y-shaped corridor of fluoro tubes, for Auckland Art Gallery. He devoted much of his energy to developing ambitious public-art-scale works, such as Coral (2000), which adorns the Vero Centre in downtown Auckland, and Saddleblaze (2008), at Gibbs Farm. In recent years, Roche had few dealer-gallery or public-museum shows and received little critical coverage, but was endlessly busy in the studio, as his intriguing Instagram posts revealed. His later work remains little seen, little known, awaiting its audience. At once a key figure in New Zealand art and something of an outlier, Roche is survived by his partner Natasha Francois and Jackson, his son with Linda Buis. We invited a number of friends and fellow travellers to remember him here. May his works never rest in peace.

—Robert Leonard

Photo: Gregory Burke

.

Gregory Burke, who documented many of Roche’s early performances; also a former Curator, City Gallery Wellington

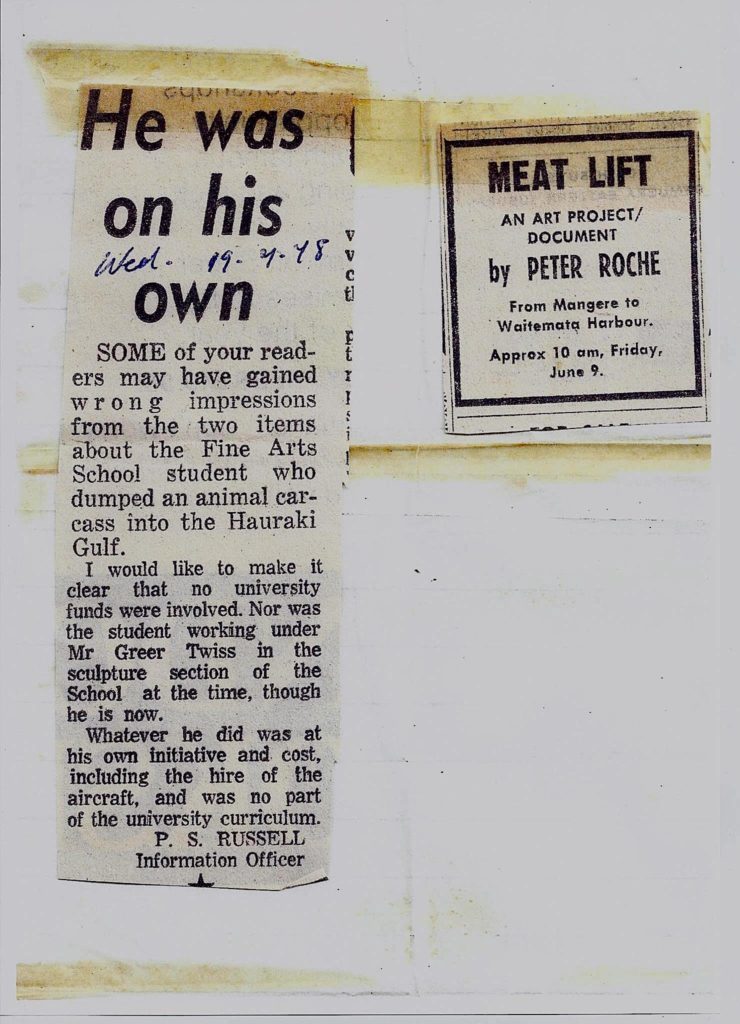

I connected with Peter Roche in the mid-1970s and was soon assisting him to document his action-based projects. I remember Meat Lift (1978). He bought a butchered sheep, engaged a pilot and his four-seater plane and hired a boat and its captain. The plan was to drop the sheep into the sea, to be retrieved by the boat, then reused in a subsequent action. That Roche managed to get the permissions was astonishing. Together, he and I flew out over the Waitemata Harbour with the plane’s left door removed. From our confined bubble in the air, he directed this action spanning land, sea, and air. As we sighted the boat, the sense of moment and scale was palpable. On his word, the plane banked to allow him to drop the carcass and for me to film its descent. Save for our harnesses, little came between us and clear air. It was precarious but we felt no fear because all that mattered was the action. Roche’s absorption was compelling. It spurred him to realise works imbued with a level of intensity seldom encountered in the art world.

In 1979, his last year at art school, Roche realised a series of solo performances that continued to court danger and were often gruelling to encounter. Many involved self-wounding, but unlike artists like Chris Burden, who in one work had himself shot, Roche’s cuts and incisions were superficial and no more harmful than your everyday body piercing. He was nothing if not ferociously disciplined, when it involved his art practice. Yet the possibility he might have gone further frequently instilled an acute sense of cognitive dissonance in his audience as he probed the psychological interaction between body, performer and self.

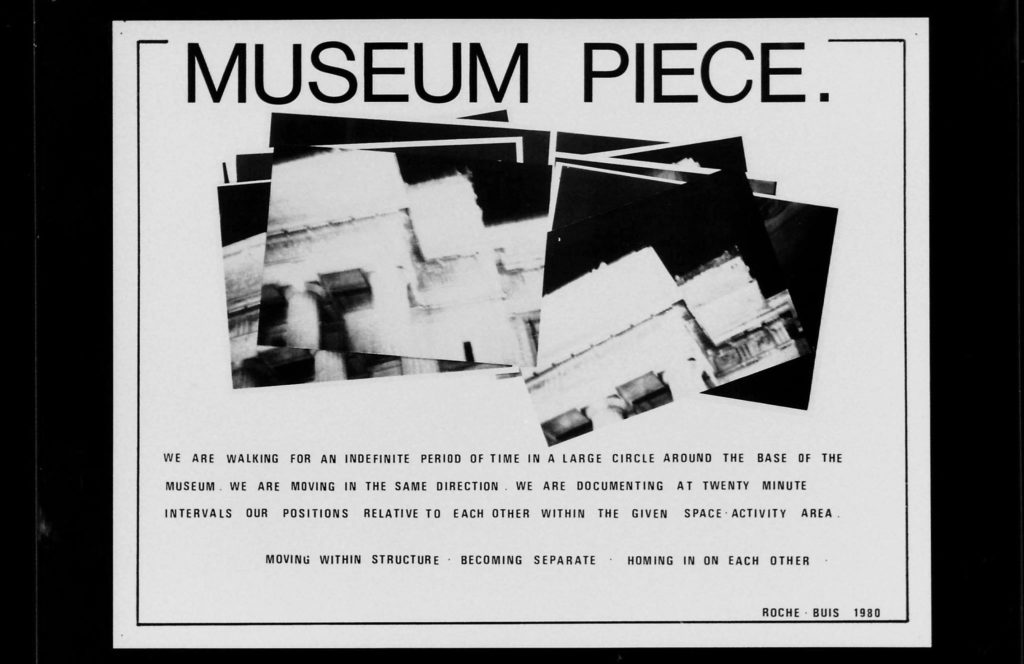

Following his graduation, Roche teamed up with Linda Buis for about five years to realise a prolific series of tandem performances, the most significant performances in his oeuvre. They were in an entirely different register to the earlier solo works. Overall, they were generally quieter and even, at times, contemplative. While, on a few occasions, the artists placed themselves in dangerous situations, their focus was more the psyche than the physical body, in works that explored what it means to be in performance and ‘in relation’—in relation to an audience, yes, but particularly in relation to another, in all its multiple dimensions. While the Roche/Buis works were less physically threatening than Roche’s earlier performances, they were as demanding and no less psychologically charged.

I photographed many of these works, with my camera mostly acting as a witness by adopting the position of the audience. There was one time though when I had to be totally in tune with the artists to get the shot they wanted. The performance was Liaison (1980). The artists stood facing each other for a considerable period of time in front of the audience and at either end of the rectangular space. The back wall was adjacent to them and faced the audience, and at its centre were a set of vertically stacked domestic mirrors. Suddenly the artists ran screaming toward each other. I had one shot, but managed to capture the moment when their heads, if not their bodies, crossed exactly at the centre in front of the mirrors. The photograph freezes a moment that the audience could not have seen clearly in the rush and roar of the action. It does, however, capture some of the intensity of the work.

Throughout his career Roche’s commitment to his practice was limitless and always uncompromising, and that never stopped.

.

Evan Webb, Director, Len Lye Foundation, New Plymouth

In 1979, as an Ilam sculpture student, I was in a herd of New Zealand artists airlifted to the Sydney Biennale, billed as ‘European Dialogue’. Our intervention—sponsored by the QEII Arts Council and lead by James Mack—was promoted as ‘Prime Export’; the poster showed a leg of lamb hanging on a hook. Were we meat—skinned, gutted, and quartered; dead on arrival? In Sydney, I fashioned a small ‘meat chain’ that rotated endlessly and asked the other New Zealand artists to hang images of themselves on it. Seasons of working at Bothwicks had left me with unpleasant associations, but my time with slaughter, entrails, shit, and tapeworms did not prepare me for Roche’s brutal, sado-masochistic performance at Marist Brothers Hall. First he showed a series of slides, showing how he had previously mutilated himself with razor blades and syringes. Then it became clear that he was about to perform the same abuse in front of us. The audience sat compliantly—he wanted our consent. This would be tacitly given, if he could, one by one, hold our gazes. Not wanting to be a lamb to the slaughter myself, I refused to play, and left before the real self harm began. But still, a measure of the power of this deeply disturbing and visceral work is that it remains with me forty years later.

.

Wystan Curnow, art critic and witness

For Peter Roche (and Linda Buis), their performances were unique and unrepeatable events. Roche would write them up while they were still fresh in his mind. Often, we would share our notes about them. Here are some extracts. These are his words:

The piece was taking up time … so far about an hour … an hour of continuous improvisation … acceptance and rejection of roles and identities, a continual assault, changing of tactics … a slow but steady draining of my defences … am cornered now … open to ridicule … more and more desperate attempts at saving face … breaking my own rules, contradicting myself in an attempt to dominate or at least get on even terms with the situation … The other provision was a razor blade which I carried in my pocket … this could be used for inscribing lines on the skin of my left forearm, thereby drawing blood … intended as a means of provocation and retaliation aimed at either myself or the image of myself in front of the audience … I attempt to re-established myself in front of myself … (July 1979)

We were quite alone. The wall was a formidable sight that night. The more we dwelled upon the piece, the larger it seemed to become. From the top of the wall there would be a sixty- to seventy-foot drop to the base of the site … things by this stage had gone too far to even think about turning back. There was nothing to be done but for one of us to climb the ladder. I went up first and lay on top of the wall … It took a lot to keep myself from panicking. Shit it was far from pleasant being up there … well, I got down quick putting on a brave face for Linda … Up she went and lay there, the ladder the only link between us now … (July 1981)

That done now … It’s the end of one thing and the beginning of another. It lies somewhere in the middle. Because of that it was by no means a smooth piece … At eleven o’clock, when people began arriving, we were already twenty minutes into the work. We wanted to be well inside the work before people entered … They way people entered was very disruptive … In previous works the audience has been free to move in and out of the work with ease, without damaging the work itself, actually becoming part of the work. But now … I don’t think this will be possible to maintain … the audience turned it into a direction we did not really intend it to go. And that’s what fucked it up in a way. We were not given enough space to get to the point we wanted to get to … (November 1981)

And something else we have not allowed to happen for some time: the closeness in proximity to each other … it has been building up this way for some time. It seems necessary that we re-establish a relationship which is accessible enough to suggest meanings outside of the work itself and yet the relevance of which is only recognised by those who are watching closely enough. (March 1980?)

When we decided to use the site it had been lying in ruins for several years. It’d been used as a rubbish dump more than once, it was overgrown … We tried to negotiate the use of the site but received a definite no from the Assembly of God which owns it and apparently intends to build a temple on it. We decided to go ahead anyhow, but of course their decision did affect our approach to the work. There were several TRESPASSERS WILL BE PROSECUTED signs on the site and we wanted to avoid trouble if we could. (July 1981)

.

Priscilla Pitts, former Director, Artspace, Auckland

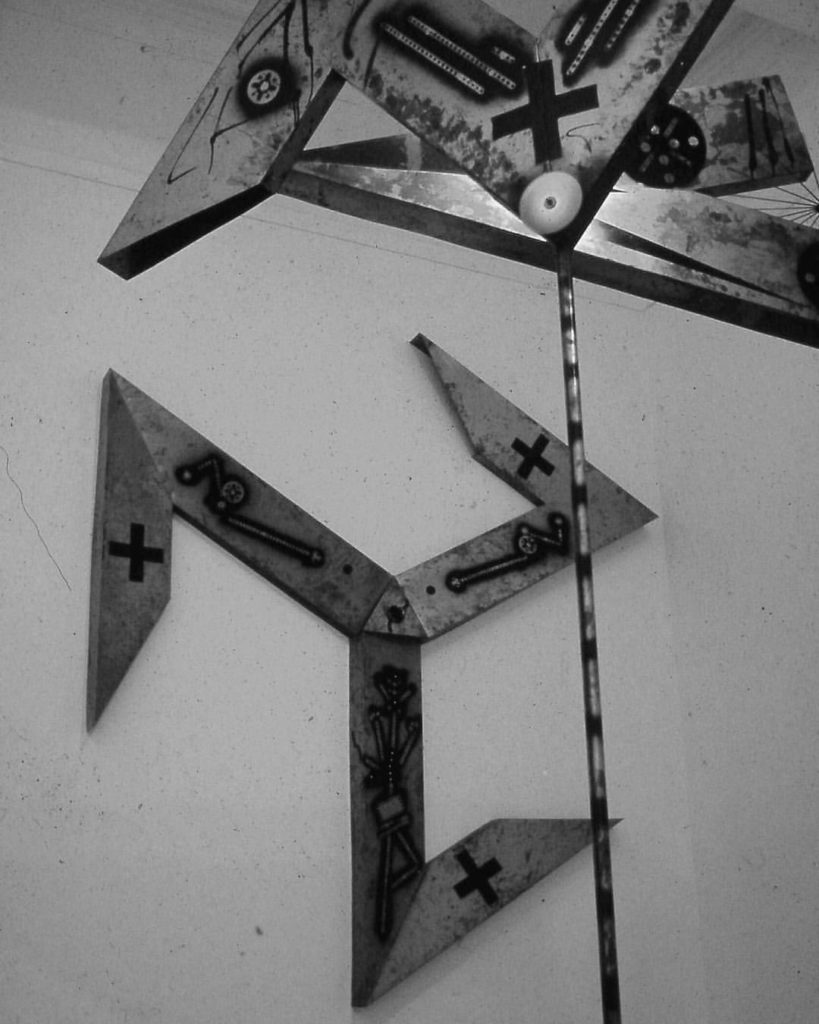

My most-vivid recollection of Peter Roche’s exhibition Trophies and Emblems at Artspace in 1990 is NOISE. His Male and Female Sentrieswere positioned just inside the entrance to the gallery and everyone who walked past set off ear-splitting alarm bells, unexpected and loud enough to trigger a heart attack. Proximity to other sculptures in the show also provoked startling repercussions. Breaching No-Go Zone’s no-go zone unleashed the noise of a pack of barking dogs while Cutter incorporated a circular-saw blade that began to screech and spin at speed whenever anyone approached.

Most of the sculptures looked menacing too. Works such as Bladerunner, Flexihead, and Harbinger were savagely angular and viciously sharp, their surfaces marked with heavy black crosses, wild scribbles, and mechanistic shapes stencilled using pieces of Meccano, the pre-Lego boy’s construction set of choice. True, there were a couple of less obviously aggressive works: Wreath, a circle of little toy wheels that almost imperceptibly kept one another turning, and a group of quietly revolving steel cut-outs that looked like clouds until you checked out the title—Volley—which suggested instead the fireballs of a bombardment.

Roche’s tactical manipulation of space and sparing use of mechanical elements (fans, an electric clock, speakers) that I’d previously experienced in his works (most of them made with Linda Buis) underwent a noticeable shift in this exhibition,with its sixteen or so individual sculptures shrieking and rattling as they reacted to visitors’ movement. Trophies and Emblems was intimidating, potentially dangerous, and, perhaps, a deliberately bellicose game.

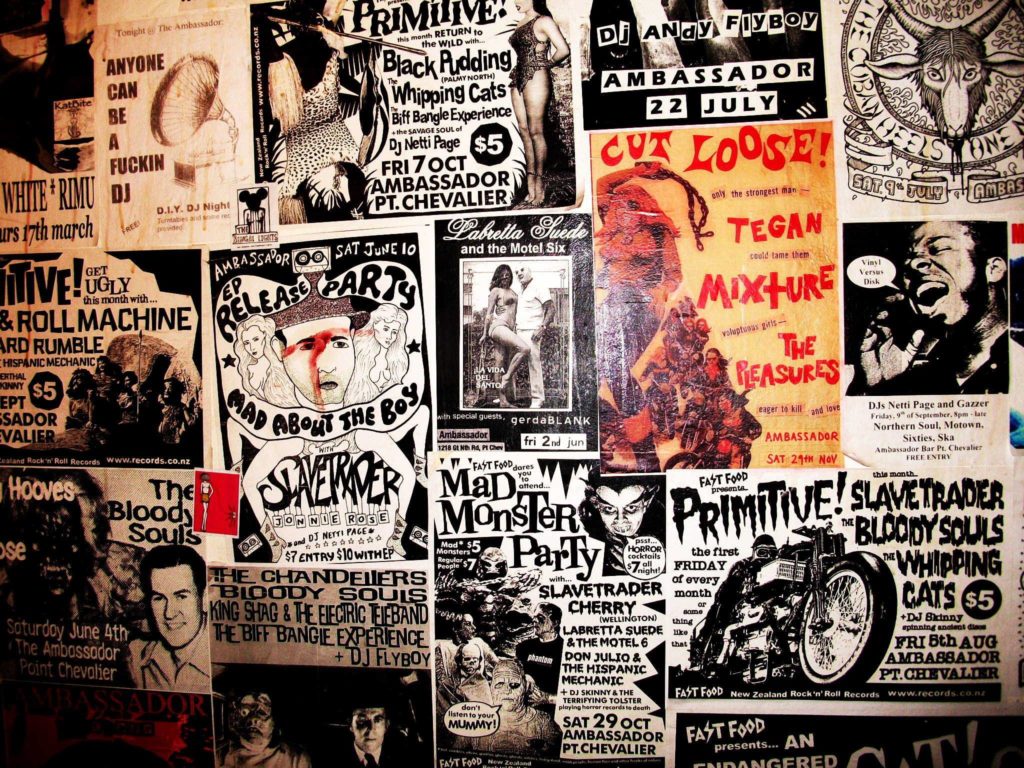

Serena Bentley, Curator, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne

For Peter Roche, life and art were innately intertwined. When I see him in my mind’s eye, he’s dancing to one of his favourite bands—Slavetrader, Bloody Souls, or Rock and Roll Machine—beer in one hand, cigarette in the other, at his beloved Ambassador bar. Formerly the Ambassador Theatre in Point Chevalier, Auckland, it became a work in itself under his ownership. A small cut-perspex work hung above the bar proclaiming ‘GO HARD FUCKERS’ set the tone. The whole place was covered in holographic wallpaper (red in the bar, blue in the bathroom, gold in his living quarters), upon which his sleek black perspex works were hung. The bar was small and narrow, until Roche opened the double doors at the rear revealing his studio in the old movie theatre. It was filled with kinetic sculptures (my favourite was a suite of little clouds, quietly rotating), acid-etched satellite dishes, and lightboxes emblazoned with depraved scenes. Roche didn’t censor himself. He mostly operated outside of the art scene and created his own scene centred around the bar. He was generous. He created a world for his friends to play music, drink, and socialise in. His work, his life, and his bar were interconnected, and that’s what made him so special. He channelled energy, movement, and light into everything he did.

.

John Hurrell, critic and publisher, EyeContact

I’m curious about Peter Roche’s shift from performance (using his body to terrorise the viewer) to sculpture (ultimately using seductive, welcoming light). He did some menacing performances later in his career and some light sculptures were also dangerous, but overall that’s the trajectory. Was one reason economic, because selling work was essential to sustain his art practice? Repulsion and fear are hard to market. Was it part of the shifting zeitgeist from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, as sellable painters (like Enzo Cucchi, Francesco Clemente, and Eric Fischl) took over from performance artists dealing in danger and disgust (like Stuart Brisley and Abramovic and Ulay)?

Roche’s interest in light can be traced back to his early 1980s night-time outdoor performances with Linda Buis using candles and torches. These works had a different kind of fearful intensity than his solo projects involving anticipated self injury (late 1970s). He used electricity in his kinetic sculpture (early 1990s), then LEDs to illuminate circuit boards (mid-1990s), then dangerous configurations of vertical fluorescent tubes (1998). From 2012 on, he seems to have been exploring neon line, chroma, and theatrical space for their own expressive sake—the sheer pleasure of doing so. By now, encouraged by the controlling influence of OSH in public art spaces, accompanying signifiers denoting ‘danger’ and ‘aggression’ had lost their edge and become faded art-historical allusions.

.

Jane Sutherland, gallerist and consultant

I met Peter Roche at Auckland University in the late 1970s. When I opened my first gallery in 1987 at City Road, I exhibited his early kinetic sculptures and drawings. It was the beginning of a lifelong working relationship. In the years that followed—from O’Connell Street to Fox Street, then for sixteen years in New York—my gallery evolved to operate primarily as a project space for sculpture and installation. From the outset, I focused on getting Roche’s work into institutional collections—public galleries, university collections, and the like—but we also began to explore addressing outdoor sites for his work, upscaling his ideas, while retaining their fragile, primal, and hypnotic qualities.

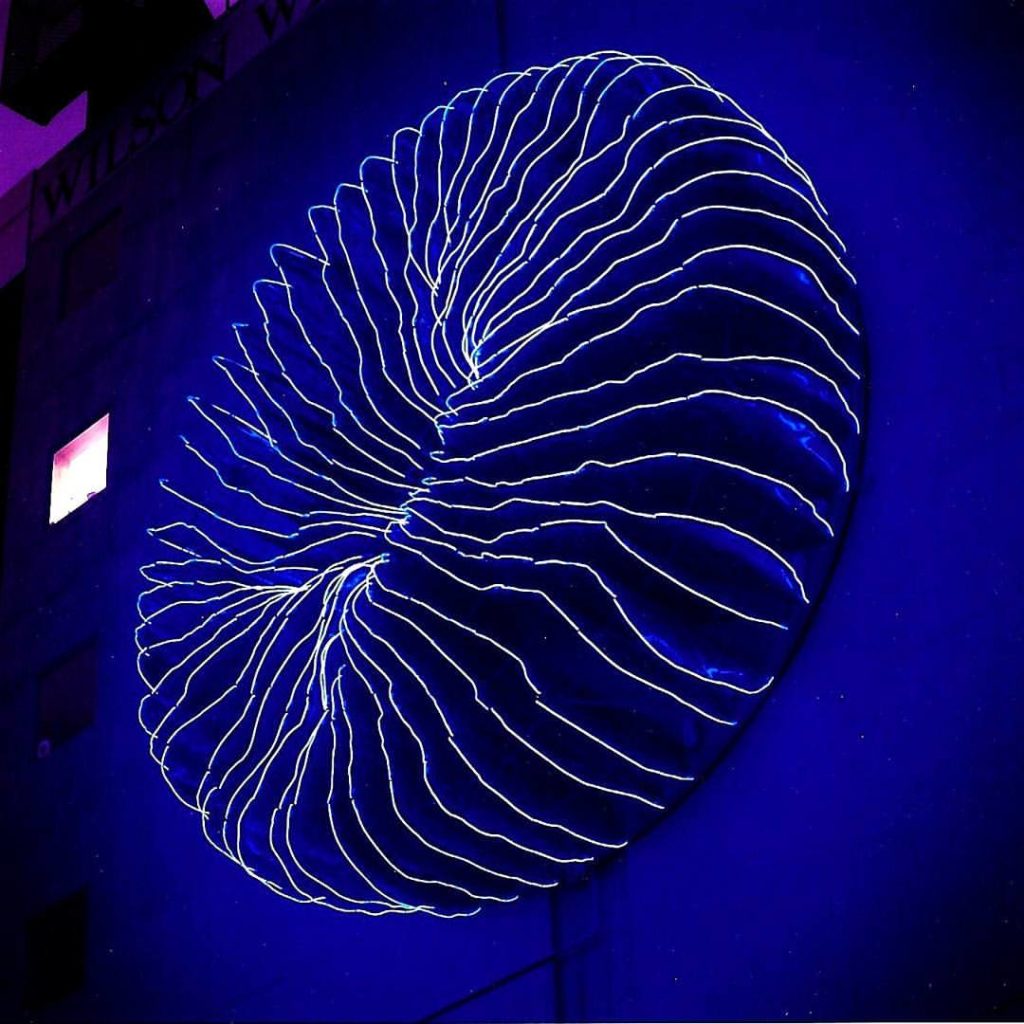

In the late 1990s, we worked on Coral (2000), an ambitious public work on the side of the Vero Centre in Auckland’s Shortland Street. It came about as a result of my many years of collaborating with Auckland architects, councils, and developers with the aim of bringing young artists’ work into the city, while also creating a way to support their practice. Coral is a steel structure, eight-metres wide, two-metres deep, that supports a delicate tracery of blue neon lines that fluctuate in intensity, slowly ‘breathing’ in unison. This kinetic drawing is live 24/7. Quiet by day, it becomes stunning by night. It manages to be monumental and fragile, combining beauty with a quiet sense of menace.

After Coral, Roche designed Twister, a monumental work for the Halsey Street wharf in Auckland’s Viaduct Harbour. Made from structural-steel tube edged with animated neon, it represented a whirlwind, with light vortices spirally skywards. Over twenty metres high, it would rest on an eight-metre wide reflection pool, creating the impression of a whirlpool beneath. In 2009, after ten years of planning, full engineering and permissions, the council shelved the multi-million-dollar project, despite funding support. It was a tragedy for Roche, his supporters, and the city.

However, Roche would realise another major outdoor piece. Alan Gibbs, one of the patrons who had supported Twister, invited him to make a proposal for The Farm, his world-renowned sculpture park on the Kaipara Harbour. While Roche presented several ideas that Gibbs loved, including Vortex, with neon tubes burrowing into the ground, Gibbs proceeded with Saddleblaze (2008). Roche used red neon tubes (later upgraded to LEDs) to light up 110 gum trees. The veins of light read as an animated drawing, moving in a seemingly infinite sequence, as if harnessing the energy of the forest. Giving the impression of an amplified living organism, Saddleblaze highlights the relationship between the trees and the surrounding environment. Roche sited the work to be viewed from within, looking down from the hills above, and looking up a steep incline, where it gave the impression of a forest ablaze with fire. Titled after the shape of a saddle in the trees, it is one of Roche’s most significant works and its use of light with trees is unique.

Roche had a deep interest in site-specific sculpture and considered his works in this area—including those at concept stage—to be an important part of his practice. Concepts include TideMark (a blue-neon channel embedded in the pavement, marking the moving tide, pointing to the ocean), and Seachange (luminous fish tanks for the plinths outside Te Papa). However, while such works were important, they remain a small part of his oeuvre. Roche continued to make dozens of works for museum settings. Asylum (2006)—his installation of kinetic sculpture, light, and sound at Silo 6 on Auckland’s Viaduct—underscored the rich aesthetic and political reach of his late work.

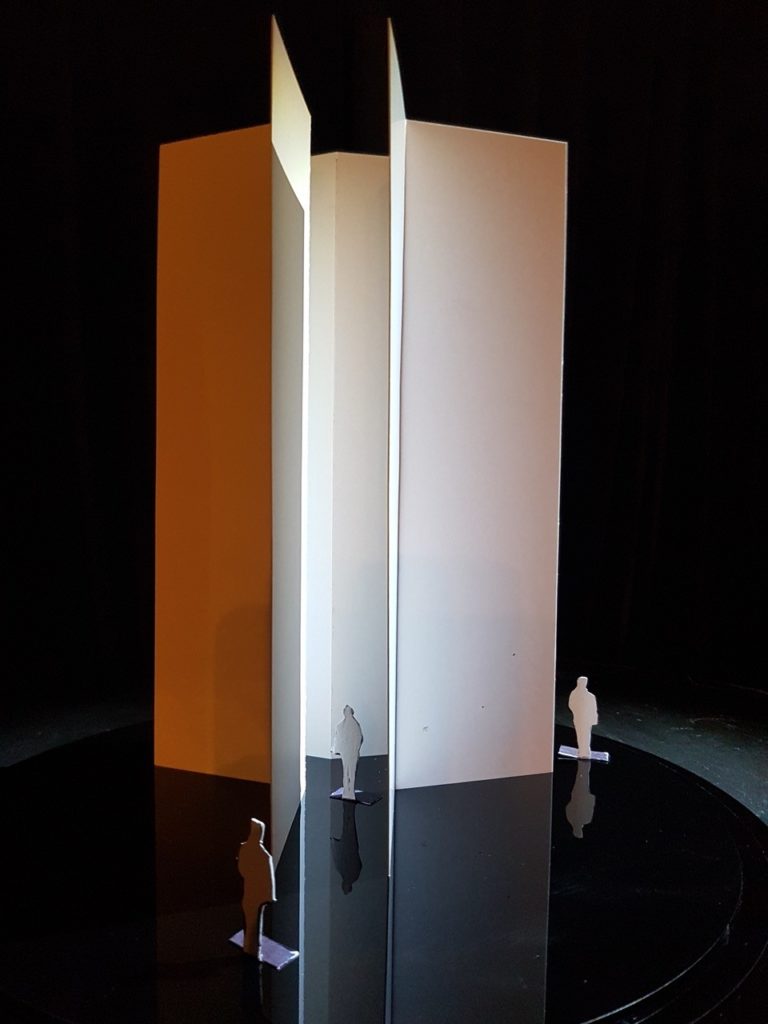

At the time of his death, Roche was in an avidly creative phase, experimenting with sculptural concepts that spoke to his works of the 1980s and 1990s. For instance, he was making drawings and maquettes for Conduit Pavilion, which riffed on Conduit, his 1998 Auckland Art Gallery installation. He had also embarked on an experimental film project revisiting work from his archive and new works in progress. Thankfully, this project will continue in the spirit he intended. He will be missed.