Wellington-based art collectors and commentators Jim Barr and Mary Barr visit an audacious art-and-community project on Chicago’s South Side.

The express ride out to Chicago’s South Side takes about half an hour. As we leave the glass-towered city, the noise level around us starts to rise until it feels as though everyone but us is talking at full volume. Someone sitting way down the back of the bus calls out over the hubbub to a friend in the front and their conversation is in turn joined by anyone with something to say on the subject. Best-ever bus ride.

We were visiting a bank building on Stony Island Avenue, an old-style bank of the 1920s, all pillars, stonework, and symmetry. If you want to get a sense of it, just think of a traditional bank in New Zealand and ramp up the grandeur. The Stony Island bank was an abandoned wreck when the artist Theaster Gates, the lead character in this story, purchased it for a dollar from the city of Chicago. There was a condition to the sale: start renovations immediately and stabilise the structure (‘you’ve got days not months’) or the deal’s off. Much of this urgent initial work was financed by the sale of a Theaster Gates art work. It was a bit of toilet humour in the form of tiles salvaged from the bank’s urinals and sold in an edition inscribed ‘IN ART WE TRUST’. That did the job. The renovations continue to this day.

The Stony Island Arts Bank is central to the Rebuild Foundation, a non-profit set up by Theaster Gates. Rebuild combines an ambitious and entrepreneurial art project with cultural initiatives and neighbourhood regeneration. The founding principles are simple: black people matter, black spaces matter, and black objects matter. From these ideas, Theaster Gates has branched out into affordable housing, community amenities, workshops, residencies, libraries, archives, studios, and meeting places. More visitor services and accommodation are coming up.

When we visited, the ground floor housed the exhibition In the Absence of Light: Gesture, Humor, and Resistance in the Black Aesthetic. It was curated by Theaster Gates out of the private collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody and anchored by artists Glenn Ligon, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, and Henry Taylor. The gallery spaces had been white-cubed, but some signs of their wrecked history have been carefully preserved: elements of an ornate ceiling, fittings from the banking past and, yes—shades of Michael Lett—a weighty old-fashioned safe. Day one, we couldn’t get access to the rest of the building so we had a drink (there was a laid-back and generous bar) and assured the people on the front desk we would be back. They definitely didn’t believe us.

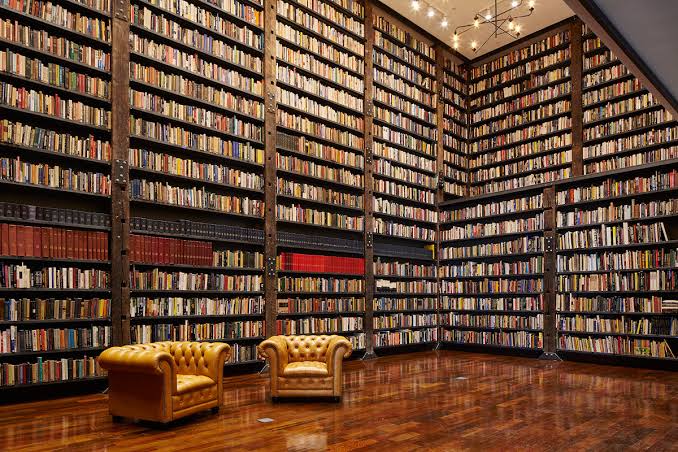

Another bus ride and the next day we were given a great welcome as we headed to the bar and waited for the official tour. As we discovered, there were in fact two libraries in the bank building, one a general collection available to anyone who drops by (another example of Rebuild’s community vision) and the other a towering and impressive presentation of a single collection.

As we walked through the building there was much talk from our guide about someone called ‘Johnson’. It took us a while to figure out who this was and why his library held such significance for Theaster Gates. Turns out John H. Johnson was Black America’s leading publisher after the second world war. Ebony magazine was his touchstone venture, but the man was a cultural powerhouse and the Johnson Publishing Company a model of successful Black entrepreneurship. Magazines, books, TV and radio shows, even beauty-care products presented an inspirational world that Johnson intended to serve as a ‘relief from the day-to-day combat with racism’. Theaster Gates obtained this impressive resource in 2015.

While the Johnson Editorial Library does focus on Black issues and history, its very scale makes real how much has been repressed and still remains ignored by mainstream America. Ladders and stairs give access to the upper shelves but for our part we were asked to stay on the floor. From there, we could note a range of titles from the many thousands: J.R. Dennett, The South as It Is: 1865–1866; Abraham Chapman, Black Voices: An Anthology of Afro-American Literature; Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God; Norman R. Yetman, Life under the ‘Peculiar’ Institution; William Peirce Randel, The Ku Klux Klan: A Century of Infamy. Shelf after shelf, row after row.

And it’s not just printed matter housed in this library. There are also shelves of vinyl records collected by DJ and record producer Frankie Knuckles, who played a major role in developing house music in Chicago from the 1980s; a collection of glass slide views of art and architecture; and the 4,000-strong Edward J. Williams Collection of objects that expose stereotypical images of Black people.

Theaster Gates sees these accumulations of history and knowledge as part of a sprawling art work. In 2012, to clear up any misunderstandings about this point, he showed a large chunk of the library as part of his show My Labour Is My Protest at White Cube in London. One quality that didn’t make it to London though was Arts Bank’s irresistible interior design and furniture and fittings. Tables and floors custom-made from the materials saved during the bank’s demolition, up-market contemporary chairs, fashionably distressed wall treatments, cunningly revealed traces of the past.

On to the final stop of our tour: the Grand Meeting Room. It deserves to be capitalised. An elegant space showcasing another dimension of Johnson’s legacy in the stylish extravagant furnishings saved from his office building. It felt like the 1970s actualised—no one on our tour would have been surprised to see Isaac Hayes and Angela Davis deep in conversation behind the gleaming curved desk. OK, maybe not, but you can dream.

We hung around and talked about Rebuild’s ideas with our guide once the tour ended. He’d started out as a casual barista and is now deeply committed to the entire enterprise. The challenges of gentrification were very real to him as we watched the tour group file out. For him the Art Bank was a possibility, a way to reboot African-American culture by a selective new reading of its objects and histories. While it’s true that Johnson himself once said, ‘I wasn’t trying to make history, I was trying to make money’, he succeeded in doing both. Theaster Gates is following a similar path as he juggles the art world and the non-art world. He wants ‘resources available through the art world [to] become additional tools that allow me to be effective in the non-art world’. He’s getting it right. As we left the next screening in the Bank’s theatre was filling up. The fact is, although participating deep in the heart of one of Chicago’s great conceptual-art projects, for the audience it was just a chance to catch a great movie.

—Jim Barr and Mary Barr