Megan Dunn talks to Jennifer Higgie, Frieze Editor at Large and host of the Bow Down podcast, which celebrates significant women from art history.

‘Can you name a non-male artist born before the twentieth century? How about two? Or more?’

‘I often just do a spot check, and people always scratch their heads. That’s why I think it’s really important’, says Jennifer Higgie, Editor at Large for Frieze and host of the Bow Down podcast.

Bow Down recognises significant women from art history. Season one includes writer Olivia Laing on Agnes Martin, Tate curator Natalia Sidlina on Natalia Goncharova, and artist Liliane Lijn on Stella Sneed, among others.

‘I sat there for a moment scratching my head’, I confessed to Jenny, after only coming up with one name: Artemisia Gentileschi (discussed by artist Helen Cammock in the inaugural episode of Bow Down.)

Higgie’s travel plans to her hometown Canberra have been postponed due to Covid-19. She was due to speak at a symposium for Know Her Name, a National Gallery of Australia initiative to celebrate the significant contributions of Australian women artists. (Only 25% of the Australian art in the National Gallery collection is by women.) Instead, she is in London as it slowly emerges from lockdown, finishing the edits on her next book, The Mirror and the Palette: 500 Years of Women’s Self Portraits.

Megan Dunn: How did Bow Down evolve from your Instagram?

Jennifer Higgie: I started my Instagram—God, how many years ago?—about six years ago. For fun, I decided to honour a woman artist who was born on each day of the year. We all know that traditional art history is a history of gender exclusion, so my challenge was to find a woman artist born each day and write a post about her. It was tricky. Each time I found a new artist, I’d put her in my calendar, and her birthday would come around every year. It seemed to chime with people’s interest and so it grew.

Then, at Frieze last year, we wanted to develop a podcast. I thought it would be nice to ask interesting people to nominate woman artists from the past to discuss. I wanted a good cross section of artists, writers, and curators to speak. I chose people I knew could tell a good story, because there’s an irony in doing a podcast about visual art when it’s not a visual medium. You need speakers who can describe the work and its context.

Actually, this interview is good timing because series two launches today, with Griselda Pollock, the great art historian who just won the Holberg Prize. She’s talking about Vera Frenkel, a Czech-born Jewish artist. Aged two, Frenkel fled the Holocaust with her family and ended up in Canada. Now, she’s in her eighties. Griselda felt she hadn’t been given her dues, so we’re starting with her. It’s a fascinating story. Eight episodes will be released, on Thursdays.

.

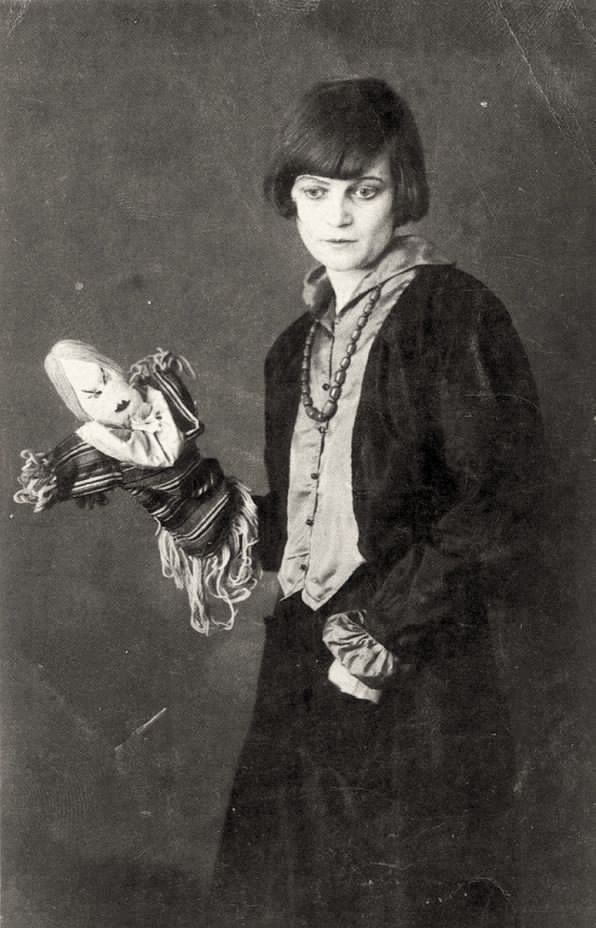

I went back through your Instagram and found your first photo, of Emmy Hennings with her dada puppet, which is still your Twitter handle. What do you know about Emmy?

She was one of the founders of dada, with her husband Hugo Ball. She was a puppeteer and poet. But I don’t speak German, and the little there is written about her is in German. I haven’t been able to find out much, but dada is one of my favourite art movements and she was a significant figure. I love that portrait of her, taken as World War I was destroying much of Europe. There’s this horror going on and she’s standing there with her puppet looking soulful—it’s absurd.

On your Instagram, Rita Angus has popped up a couple of times, on her birthday.

I repost every year, so I don’t have to write these histories afresh, I just update them. Rita Angus also features in my book, The Mirror and the Palette, which is out in March 2021. There is a section on her in a chapter about translation. I look at women who were working within a European idiom, but reconfiguring it to their local concerns. I discuss Rita Angus, Margaret Preston from Australia, Amrita Sher-Gil from India, and Lois Mailou Jones from the US, looking at their self portraits and what they say about their individual histories and their particular cultural moments.

In the age of the selfie, there’s a tendency to assume that self portraiture implies narcissism, but that’s not the case historically. In episode two of Bow Down, Shahidha Bari discusses the painters Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffman, both founders of the Royal Academy in London in 1768. Unlike their male contemporaries, they couldn’t access live sitters, so Moser specialises in botanical paintings while Kauffman paints portraits of herself.

Many women excelled in self portraiture. They weren’t allowed to paint naked models in the life room, so they turned to themselves as subjects. If they had a mirror and a palette, they could paint themselves, which is why I’ve called the book The Mirror and the Palette. My book stops at 1980 with Alice Neel’s great self portrait, naked, aged eighty. I stopped there because my focus is painting, and because, once you get into the twenty-first century, the era of the selfie, it’s a whole different thing. Neel took five years to paint her self portrait, compared with a shutter closing in a split second.

Bow Down is a beautiful name. How did you come up with it?

It started out slightly jokey: let’s pay homage to these women, let’s ‘bow down’ to them. I started tagging it at the end of my Instagram posts, then it became the title of the podcast, and now I’ve also changed my Instagram to it. It feels quite weird having an Instagram called Bow Down. If I stop doing the podcast, I’ll change my Instagram back to my own name.

the Arts of Music and Painting 1794

.

After Moser and Kauffman, it’s 168 years before there’s another female Royal Academician. How much has Bow Down been about discovery for you?

It’s been an education for me, as much as for anyone else. I went to art school in the 1980s and 1990s in Australia. I didn’t know that the first self portrait at an easel was painted by a woman in 1548. I didn’t know that women had been active as artists throughout history—though less so than men, because they had so many hurdles. To be a woman artist in the sixteenth, seventeenth, or eighteenth centuries took balls. I shouldn’t really say ‘balls’, but you know what I mean. I’ve learned so much in trying to find a woman artist born each day. I’m extremely aware of the exclusions and absences. For example, to find the names of historical women artists in Africa is very difficult. In my book, I focus on European art history, but for my Instagram I have honoured the work of Australian Indigenous artists.

You were co-editor and then editor of Frieze from 2003 to 2019. What do you think changed in those years for women artists?

When I started at Frieze, I used to jump up and down about representing women equally in the magazine. I got the sense that some people thought I was being a pain in the ass. Magazines reflect what’s going on in the world. At that stage, galleries would not give a thought to their representation of women. Most commercial galleries were overwhelmingly representing white men. Class and race is obviously another huge thing here, because there’s now so much discussion about representation of people of colour. The art world is very middle class. The good thing is now galleries are scrambling around to redress the imbalances in their representation of artists, be they women artists or artists of colour. Galleries are undergoing so much scrutiny, but it’s a recent shift. Even now, there are major galleries who still only represent a tiny percentage of women.

.

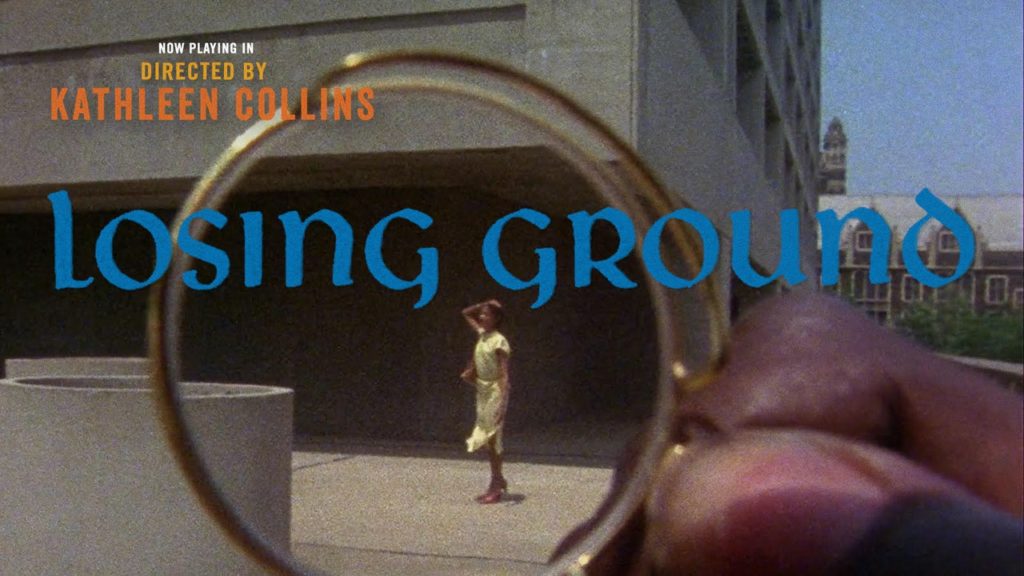

Listening to Bow Down, I was struck by the recent major omissions and discrimination. I’d never heard of the filmmaker Kathleen Collins. It was shocking to realise that, in 1981, when she made Losing Ground, she was the first African-American woman to write, direct, and produce a feature film.

It’s extraordinary, isn’t it?

Yet, when I went through art school in the mid-1990s, I didn’t feel limited by my gender.

That’s a very good point. I didn’t either. I didn’t feel discriminated against at art school. I assumed that, in the European tradition, women in the past didn’t make art but that now we are allowed to, rather than realising that in the past so many women had made art.

With the podcasts, I admire you for sticking to the twenty-minute format. Were you ever tempted to go longer?

We might go longer in future, but I like twenty minutes. It’s quick, it’s not overwhelming, people can listen while they commute. We want to pull in an audience of people that are interested but aren’t necessarily art-history experts. The twenty-minute format is enticing.

Can I get you to name a darling? As the host of Bow Down, you’re not in the hot seat. But, if you had to nominate a women artist, who would it be?

The Renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola (1532–1625) was extraordinary. She was born in Cremona, in Northern Italy, as one of five daughters. Two of her sisters also became artists. Her father really promoted their talents. But he wasn’t an artist, which is unusual, because, with most women artists from those days, their fathers were.

There’s a great story about her sending a drawing of a little girl laughing to Michelangelo. He wrote back saying he’d rather see a picture of a little boy crying because it was harder to do. She sent back a drawing of a little girl teasing a boy who’s crying. It’s likely that she studied with Michelangelo unofficially. Then she became a court painter for Philip II of Spain. She was married off at forty and never had children. Her husband died in mysterious circumstances—murdered by Albanian pirates. Then she went back to Italy and fell in love with a much younger sea captain, who she ran away with, and became one of the most famous artists in Europe. People would come from all over to see her.

She ended up in Palermo. In her late eighties, Van Dyck, the English painter, came and saw her, and did an amazing portrait of her as an old woman. She was just such a character. She backseat painted while he was doing it. He wrote in his diary that he learned more from her than he had in all of his life being taught art. Between Durer and Rembrandt, Anguissola was the most prolific self portraitist but we were never taught about her.

How long has The Mirror and the Palette been evolving?

I actually did it really quickly. I put in a proposal early last year that got bought by Weidenfeld and Nicolson, so I had a year to write 100,000 words. At that point I was still full time at Frieze, so last year was tumultuous. I was working on it nonstop whenever I wasn’t at Frieze. And then I decided to step down as editor of Frieze. I got a three-month sabbatical and went to Canberra and stayed with my mum and went to the National Library in Canberra. I set myself a daily 2000-word limit. I worked in a frenzy getting it done, which is slightly terrifying now it’s being published. I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I wrote it so fast.’ But, after being an editor working on other people’s writing, it was liberating to focus on one big piece of my own.

How did you decide on the structure?

The book includes women artists from about fifteen countries and spans from 1548 to 1980. I broke it into themed chapters: self portrait as hallucination, self portrait as solitude, self portrait as translation, and so on. It’s a very idiosyncratic selection. I’m sure people will think, why didn’t she choose to do this or that other artist? But, I make it clear, it’s just artists that I responded to and who sparked my imagination. It was also about women who had good stories. For instance, I remember seeing Rita Angus at Te Papa—I’d never seen her work before. I was like, oh my God, this is extraordinary. Rutu, her self portrait as a goddess, is such a strange fusion of references to Polynesian and European cultures.

.

What changes over time in women artists’ self portraits? What broad changes can you track?

Broadly speaking, for quite a few hundred years, from say the sixteenth to the early-nineteenth century, women artists had to make it clear that they were also virtuous women, because they were dabbling in a male profession. In seventeenth-century England, it would be published that an artist was a virtuous woman, so that people could come and sit for her as a portraitist and she wasn’t considered a prostitute, for example. Sofonisba Anguissola is constantly making it clear that she’s a virtuous woman. Artemisia Gentileschi, one of the great baroque painters, also does. Although she pictures scenes of terrible brutality, she’s painting women and herself as saints—her murderous Judith is a virtuous woman. Because, if you weren’t a virtuous woman, you were excluded from society. And then you get to the early-twentieth century, and you’ve got the great German artist Paula Modersohn-Becker doing the first naked self portrait. It wasn’t exhibited in her lifetime. She made her self portraits in private.

.

The reception of Hilma af Klint seems a signature moment in readdressing the art-history canon. You’ve written about Hilma’s work. Why do you think the world is so ready to receive this work now?

To my mind, the staggering popularity of the Hilma af Klint show at the Guggenheim—it was the most popular show in the museum’s history—is a reflection of a contemporary hunger for alternative ways of understanding and perhaps escaping or transcending the complexities of the world. Given the crises the planet has experienced in recent times—from the ravages of climate change to the devastating fires in Australia, California, and the Amazon to the horrors of the Covid-19 pandemic—it’s clear that the foundations of what we assume to be true and fixed, from politics, to the natural world, and religion, are wobbling. Parallels could be drawn between our contemporary moment and the nineteenth century, when, in the West, there was an explosion of interest in spirituality. It was a time of enormous cultural, environmental, and technical change, which made other dimensions appear not so much improbable as desirable. Also, at this post-#metoo time of heightened female empowerment, there’s a hunger for an art history that rejects more traditional, male-centred narratives—which is essentially how modernism has been taught. And finally, they’re amazingly beautiful paintings. You don’t need to know anything about art to be moved by them.

You are an art-industry insider. You have been on selection panels for prizes, including the Turner, and have seen how careers are advanced. How do you think the art industry needs to change to create an equitable future in which we don’t have to ‘bow down’?

I think that there has to be a greater awareness that the traditional story of art—a story that’s told through the lens of white-male achievement—isn’t the only story. Art has always been made by everyone. It’s time to honour that.

.

.

This interview is published in partnership with Verb Wellington as part of the series ‘Art History Is a Mother.’ The first essay in the series is Many Mamans: Art Mothers and Monstrous Practice by Sinéad Gleeson.