They say art can change the way we look at the world, but the world can also change the way we look at art. I asked some friends to join me to comment on art works that look different in the pandemic. Here’s the second instalment. Contributions are presented in the order received.

—Robert Leonard

Christina Barton (Director, Adam Art Gallery, Wellington): I have two works in mind. As our own city streets are empty, I’m enjoying Thomas Struth’s photo Crosby Street, Soho, New York (1978). I’ve always loved Struth’s deserted, deadpan views. Shot from the middle of the street, early in the morning, when no-one is around, they are literal demonstrations of how perspective works, catalogues of the systems and structures that define human existence, and meditations on different orders of time. But, now, when I look at them, I can’t quite tell whether I’m looking at the past or the future. I’m also thinking about how good we are in lockdown, obedient and trusting. It is, of course, the right way to be. But I can’t help being reminded of the group-portrait video, Sixty Minutes Silence (1996), that won Gillian Wearing the Turner Prize in 1997—a bunch of policemen and policewomen required to pose for an hour, and the mayhem of wriggles that ensues as they struggle to last the duration.

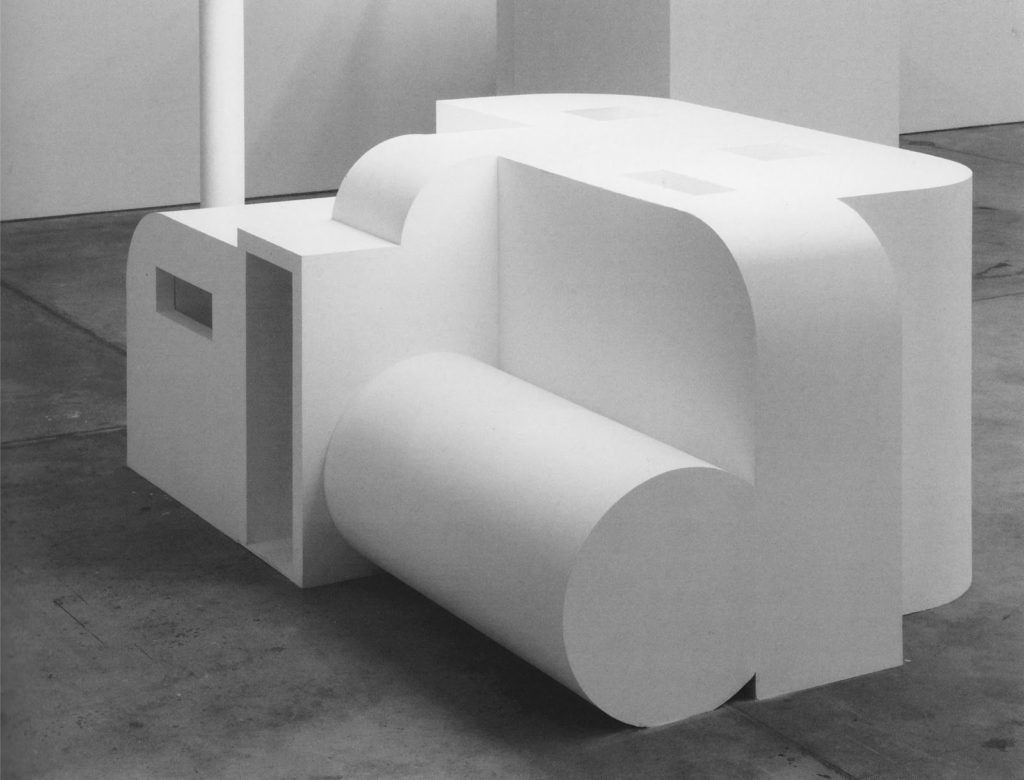

Helen Hughes (Research Fellow, Faculty of Art, Design, and Architecture, Monash University, Melbourne): I’ve been thinking about Absolon’s Cellules as I read about the threat Covid-19 poses to overcrowded prisons in Iran, the US, and Turkey; to homeless populations and overcrowded poor communities worldwide; and, more selfishly, as I bat toddler twins—and a cat—off my keyboard while trying to write this. Absolon’s Cellules are 1:1 prototypes of architectural dwellings designed to be inhabited by a single person. Perfectly white, minimal, unadorned, and tailored exactly to the dimensions of the artist’s own, nearly two-metre-tall body, they are an architecture of bare minimums. In this way, the Cellules are structurally related to the prison cell or coffin, or, as one critic supposed, a ‘return to the womb after the failure of the external world’. Six house cells were to be built in total, one in each of the six busy metropolitan cities where Absalon planned to exhibit his work before his premature death from another contagious and deadly disease, at age 28, in 1993. These cities predictably included New York and Tokyo, now the virus’s hot spots and epicentres. Foremostly a mental architecture, the Cellules’s purpose is to condition the behaviour of their inhabitants—to facilitate a means of better living inside one’s head, indeed of collapsing the categories of mind and architecture altogether. While, on the one hand, they reek of neoliberal individualism, self-dependence, and atomisation, they are also deeply spiritual structures, developed after a failed stint living out in the desert with Bedouins. The Cellules also adapted the asceticism of Anchorites—who in the Middle Ages would brick themselves into four-walled cells attached to churches, where they would read, write, pray, and achieve acute forms of contemplation and devotion, then eventually die—to globalised, twentieth-century life. They are an architecture for shedding objects and obligations, cultivating new ones, turning away, inward, then disappearing. An architecture of retreat and withdrawal, of burying oneself alive in order to, paradoxically, survive. The Cellules were, said Absalon in the year of his death, his ‘solution to living in society’.

Allan Smith (Senior Lecturer, Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland): After we had exchanged some email drolleries last week about the late Paul Cullen’s prescient and covert Covid-19 art, Layla Tweedie-Cullen sent me an image of his doctored globe. Dating from around 2010, it’s an audacious paperweight to toy with like a spiny mini massage ball; it’s a dainty variant on the cup-hook and screw-eye-festooned objects Tony Cragg made in the late 1990s; and it’s a souvenir-shop variant of Chris Burden’s Medusa’s Head (1990), that concrete-and-steel planet strangled by its capacity to encompass and connect itself. Like the now-ubiquitous, digitally modelled, graphically augmented coronaviruses multiplying across screens and imaginations on the alert—while the real microscopic pathogens attack respiratory and nervous systems worldwide—Cullen’s garlanded globe bristles with a menacing conviviality, a drive to survive that turns on the capacity to connect. His cloud of cup hooks drilling into the planet’s surface enacts a global trepanning—with country colours mimicking phrenological zones—to relieve accumulated pressure by exactly co-ordinated increases in pressure through helical turns of the pain screw (that satisfying twist of the cup-hook as it bites tight!). It also resembles the coronal measles virus—so the artist may have had in mind infections of his youth as well as future pandemics. Given that coronaviruses employ their projecting spicules to hook onto receptive cell surfaces when they want to move in, not only will the term ‘viral hook’ and ‘going viral’ mean differently now, but we get yet-another disconcerting reminder of the way generative surges, exponential increase, prodigal inventiveness, and extraordinary adaptation are all traits shared by capital, creativity, and contagion.

Lara Strongman (Director Curatorial and Digital, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney): I’ve long been partial to Albert Pinkham Ryder’s painting The Race Track, also known as Death on a Pale Horse. He painted it in the US at the beginning of the twentieth century, but it’s resolutely antimodern. It’s like a panel from a pre-Renaissance altarpiece from somewhere in provincial Europe. It’s out of place and out of time. Before Covid-19, I’d google The Race Track every now and then, drawn in a certain melancholy or antagonistic mood to its deliberate anachronisms, its lyrical miserabilism, its sheer tastelessness. I liked the way the clouds in the leaden sky mirror the form of the galloping horse, and the way the snake—an emblem of both evil and of learning—prevents you getting too close. The pale rider is the fourth horseman of the apocalypse in the Book of Revelation. Pinkham Ryder painted the work following the suicide of a friend, but he filled it with ancient darkness. Over the past few weeks in lockdown, though, I’ve been looking at it differently. It’s suddenly re-situated itself in this time and place. For the first time ever, I’ve thought about the title of the painting: Death is the only rider on the race track, and he’s coming round again.

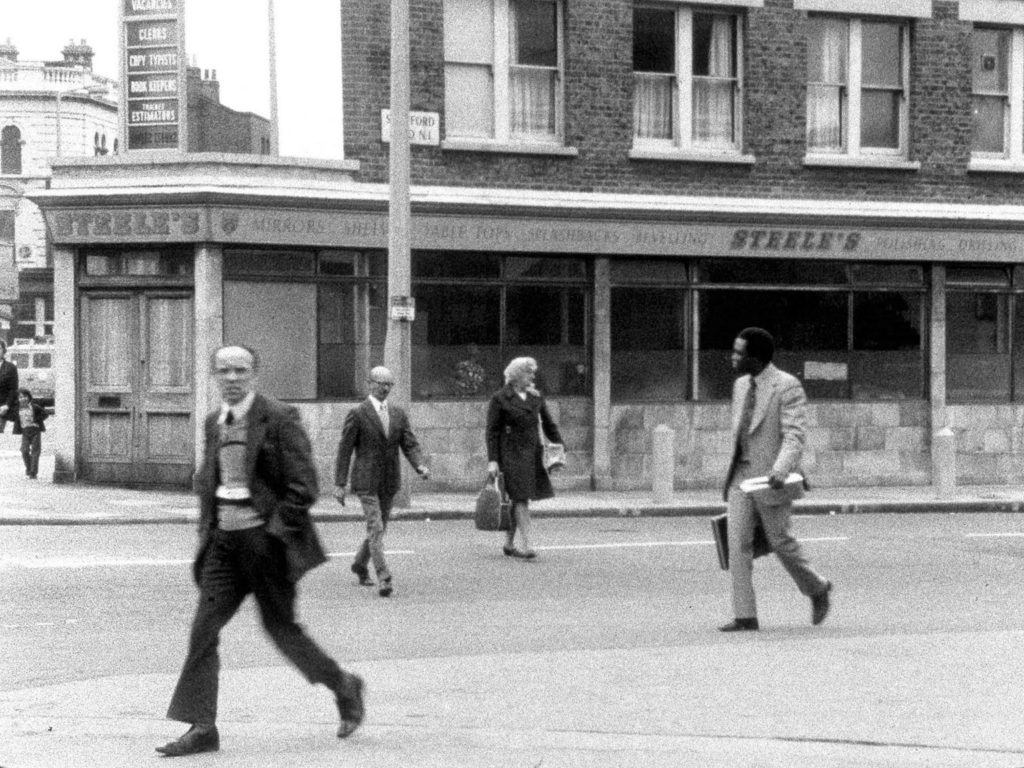

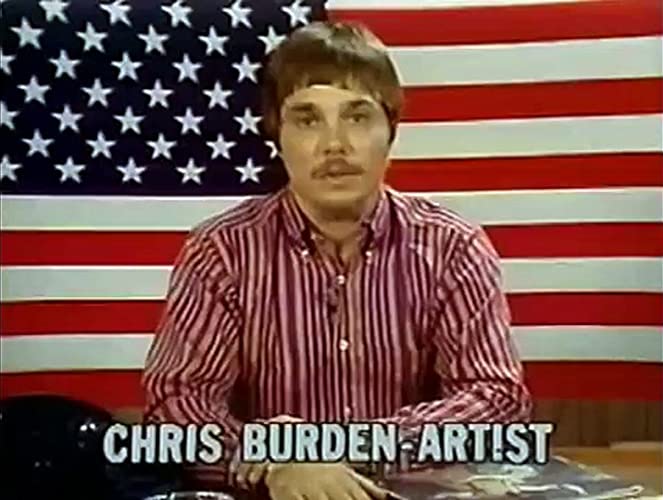

Joel Stern (Senior Curator, Liquid Architecture, Melbourne): Stuck inside, worrying about money, two works come to mind: John Smith’s 1976 film The Girl Chewing Gum, made at the London Filmmakers’ Co-op, and Chris Burden’s Full Financial Disclosure, an advert the artist paid to place on community TV in California in 1977. Both are hilariously deadpan, gently bleak, and speak to the feeling of having more time on your hands than anticipated. In Smith’s film, the artist points a 16mm camera out a window in Dalston Junction, east London and narrates the everyday street scene as if he is directing it, commanding people, objects, even time itself, to move here or there. The narrator turns everything into a staged performance. At the film’s end, Smith reveals himself to have been shouting into a microphone from a field some miles away, far from the action. The reveal, of course, is unnecessary, making it even funnier; the fakeness of the conceit, nested within real life as it is, is evident from the start. That’s why The Girl Chewing Gum, despite its tricksterish mercurial quality, is considered a classic of anti-illusionism, and well aligned to the Co-op’s politics of demystification and transparency. Burden’s advertisement is also an exercise in demystification, of himself as a ‘successful’ artist. Sitting in front of an American flag, reflecting what he calls ‘the post-Watergate mood’, he summarises his finances, revealing a depressingly minimal net profit for the year. That the artist has paid for the airtime to inform us of this is perfect; it’s the most commercial platform possible from which to advertise one’s economic unviability. As the art economy collapses around us, I’m craving another work as funny, honest, and reflexive as this. For me, the disposition of both works—detached, transparent, self-deprecating, comic—is comforting, maybe even instructive, in trying to process this unfolding moment in all its grinding unreality, repetitiveness, and banality. And the methodology—of arriving somewhere enduringly real in the deployment of a construct—is a good argument for the ongoing utility of art.

Peter Shand (Associate Professor, Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland): The current situation makes more acute our embodied understanding of existential phenomenology. Physical, intellectual, and emotional relationships are profoundly altered, as is our relationship with the self. We find new forms of engagement (or expand those we already have), but these are landing very differently, if at all. I think of the impact of Diamond Reynolds’s Facebook live streaming of Philando Castile’s death in the carseat next to her in 2016. The extraordinary public visibility of her trauma propelled online and media political dissent, but it didn’t galvanise physical protest as directly as had others in the too-long list of discriminatory police killings. The urban geography of Saint Paul intervened to make that difficult. Where were the gathering places? What mode of public address might be available? Shared online, Autoportrait (2017), Luke Willis Thompson’s collaborative portrait of Reynolds—a sister work to hers—itself became caught in a digital looping estranged from the experience of the work. Stripped of the relentlessly violent clacking of the projector, of the cool emptiness of the installation space, and the scale of Reynolds’s projected image, the complex interweaving of its political ambition with its aesthetic operation qua art was compromised. I can’t help but see this as a loss, a diminution not just of art’s capacities but of ours. Observing this now, I’m further caught in the same digital snare, estranged from the world. It makes me anxious and filled with longing for the holistic, transformative propulsion of artistic experience in the world, of personal connectivity in places of public gathering.

And a second thought from Helen Hughes: Like many, I was tickled by Boris Johnson’s proud statement during a press conference last month that, against all the medical advice, he shook hands with a number of confirmed Covid-19 patients. Weeks later, in what can only be described as karmic justice, he tested positive for the virus himself and wound up in Intensive Care. Listening to BBC news around this time, I was struck by a discussion on whether or not the handshake will return post-Covid-19, or whether this cultural gesture of peace and goodwill may fall on the trash heap. Perhaps tellingly, Dr Anthony Fauci recently advised Americans never to shake hands again. Against this backdrop, I keep returning to Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s piece Touch Sanitation (24 July 1979–26 June 1980), in which she shook the hand of every sanitation worker of New York City (approximately 8,500 people) in an effort to render their labour more visible, as well as to undermine the sense that waste handling is an activity that should occur at a geographic and social remove. As part of her ‘maintenance art’ program, which sought to highlight the worth of the often unpaid or underpaid labour of women and migrants in the US, Touch Sanitation formed a symbolic union between women and service workers more broadly. Today, at a time when workers who are also mothers are disproportionately disadvantaged by lockdown restrictions, when hordes of essential-service and care workers don’t even have the choice to work from home despite the health risks, and when new forms of solidarity that don’t involve standing shoulder to shoulder in public space need to be imagined, this union feels more crucial than ever. The inherent, nauseating danger represented by Touch Sanitation—like Boris Johnson’s handshakes—in the time of coronavirus prompts this act of imagining otherwise.