They say art can change the way we look at the world, but the world can also change the way we look at art. I asked some friends to join me to comment on art works that look different in the pandemic. Contributions are presented in the order received. More next week.

—Robert Leonard

Robert Leonard (Chief Curator, City Gallery Wellington): I’d like to propose German artist Franz Erhard Walther as a poster boy for social distancing. Since the 1960s, he’s been making minimalist-looking fabric objects for gallery goers to occupy and articulate. With their openings, fastenings, and straps, they are less sculptures than activities—performance scores. His body bags regiment populations into lines, shapes, patterns, tableaux, while his wall-mounted works hybridise clothing and architecture. Restricting yet benign, and often rather cosy, they suggest social structures, permutations of independence and interdependence—snapshots of group dynamics. But his work is never an orgy. He doesn’t press bodies together, demanding respectful distance, equal personal space. Indeed, his works are all about getting together without touching. Now, with the pandemic, much of it looks like experiments in repressive-for-your-own-good social-distancing technology.

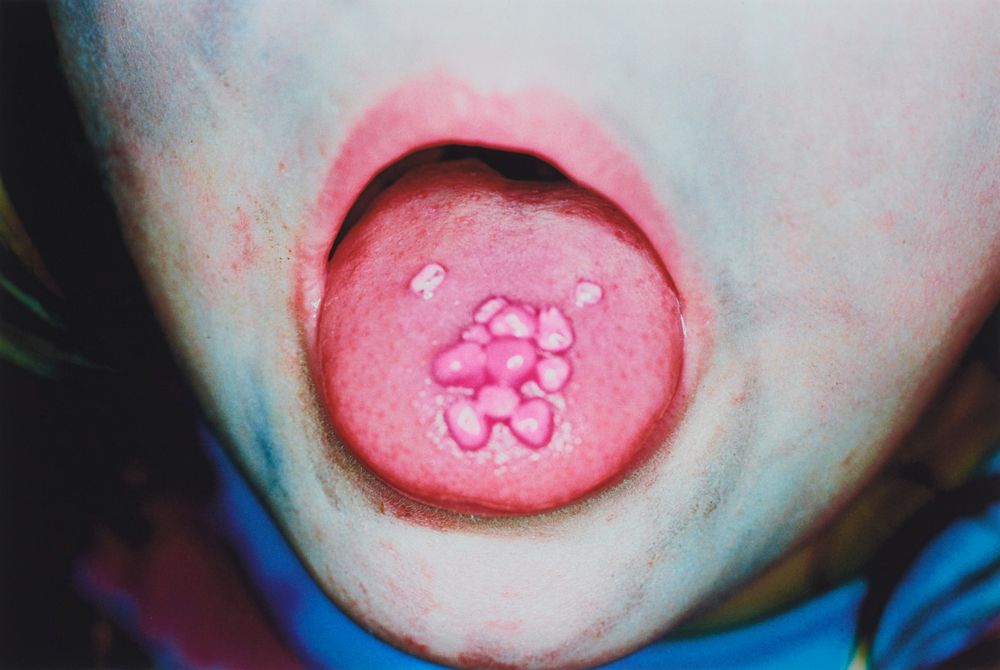

Chelsea Nichols (writer, Ghuangzhou and Ashburton): The pandemic gives a new horror tinge to works like Max Oettli’s Girl Licking Escalator (1972) and Anne Noble’s series Ruby’s Room (1998–2007)—lurid closeups of her daughter’s mouth with things in it. Knowing that children are often asymptomatic carriers and spreaders, these mouths look creepier than ever. The potentially germ-infested tongues of these tiny Typhoid Marys are capable of wreaking havoc. I also can’t stop thinking about Janine Antoni’s Lick and Lather (1993), seven chocolate self-portrait busts and seven soap ones. Both sets have been worn down, the chocolate ones through licking, the soap ones through washing. The chocolate busts have lost their sensuality, as I fixate on the invisible layer of disgusting saliva that coats them. Licking a face has shifted from something erotic and intimate to a threatening act of potential transmission. Stop touching your damn face, Janine! At the same time, the reshaped soap busts have become oddly reassuring icons of safety and salvation, made from a humble substance suddenly repositioned as a precious material.

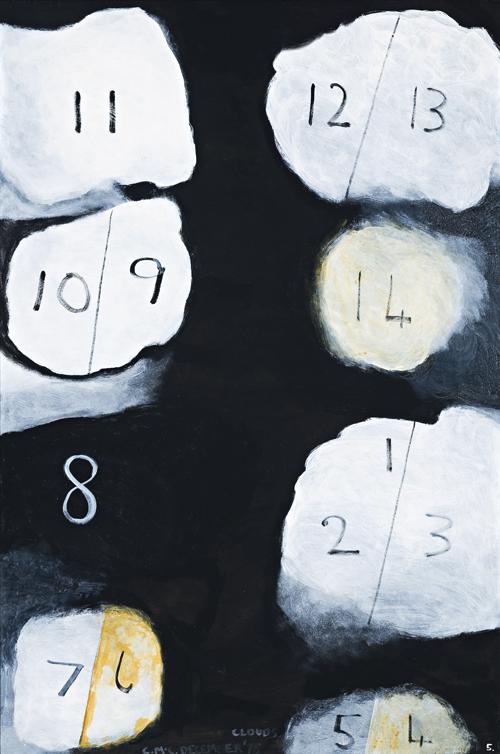

Rex Butler (Professor of Art History, School of Art, Monash University, Melbourne): The best thing I have read so far on the Covid-19 virus is ‘The Great Mutation: Ravings from the Bedroom Bunker’ by young Melbourne philosopher Vincent Le. His amusing point is how well the virus conforms to all the great contemporary philosophers’ favourite themes and obsessions. Thus, for Giorgio Agamben, the virus is ‘an excuse for the biopolitical enforcement of a completely superfluous state of emergency that would suspend our democratic rights’. For Slavoj Žižek, it is merely the occasion for us to think again the necessity of a ‘global communist revolution’. For Alain Badiou, the current situation, characterised by a viral pandemic, is ‘not even particularly exceptional’. As opposed to all of these predictabilities, Le suggests, almost hopefully, at the end of his essay that ‘all we can say for sure is that something, some future horizon, some unknown land, is about to go viral’. In the light of Le’s brilliant diagnosis, what I am going to say can only sound disappointing. If I had to think of a work of art that now took on a renewed relevance in the light of Covid-19, I too can only come back to what I already know. In the lockdown, a colleague, Laurence Simmons, and I are writing a book on Colin McCahon—all too late, I know—and my mind immediately goes to McCahon’s Clouds 5 (1975). It’s all there: the deadly miasmic clouds, the slowly or rapidly increasing numbers, the hint at dark mortality. Maybe they should use this as a poster for social distancing. I’d sure stay away from everybody if I saw it.

Andrew Paul Wood (writer, Christchurch): I’ve been thinking about Albert Bierstadt’s Valley of the Yosemite (1864), the painting suspended over Bruce Willis in the hospital bed the first time he returns from the past in Terry Gilliam’s film Twelve Monkeys (1995). In that movie, humanity has been driven underground by a deadly viral pandemic originally created as a biological weapon and accidentally released from the lab by animal-rights activists. Presumably, in the world of the movie, the painting was seen as valuable and important enough to have been rescued from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston before the Earth’s surface became uninhabitable for humans, but has been reduced to a mere therapeutic decoration. Bierstadt’s painting, an exercise in nineteenth-century Hudson River school high romanticism, represents the calming and restorative power of nature, the outdoors. Ironically, the physical outdoors is as beyond reach in the reality of the movie as it is in the painting. We are passing through a historical moment that can only be defined or succoured by romanticism: the isolated self confronted with an overwhelming transcendental natural phenomenon before which it is helpless. At the moment I think a lot about landscape painting because it represents an outdoors that I can’t properly access right now, and still life because that consists of things close at hand within my bubble.

Simon Ingram (artist, and Senior Lecturer, Elam School of Fine Arts, Auckland University): As we all find ourselves isolated in our homes, going stir crazy, Russian artist Ilya Kabakov’s installation The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment (1982–4) resonates as escapist wish fulfilment. The installation is a small room festooned with Soviet-era posters expressing enthusiasm for progress, technical notations, a painted cardboard model of land and atmosphere, and a camp bed. Two chairs, straddled horizontally by a sturdy plank, sit below a contraption resembling a catapult. The blast hole in what is left of the ceiling is evidence of a speedy departure from the room. The motive force behind this launch is both mechanical (a person catapulted) and ideological (an ‘illegitimate cosmonaut’ has been charged-up by Soviet-era propaganda posters). Utopian dreams of a cosmic future shared by and for the people have—as Boris Groys put it—‘been purloined under the cover of darkness, privatised, and misused for one person’s private, lonely ecstasy’. The apartment is less office of the Soviet space programme and more artist’s studio as crime scene. Someone has gone rogue, busted out, and transcended the materialist conception of history.

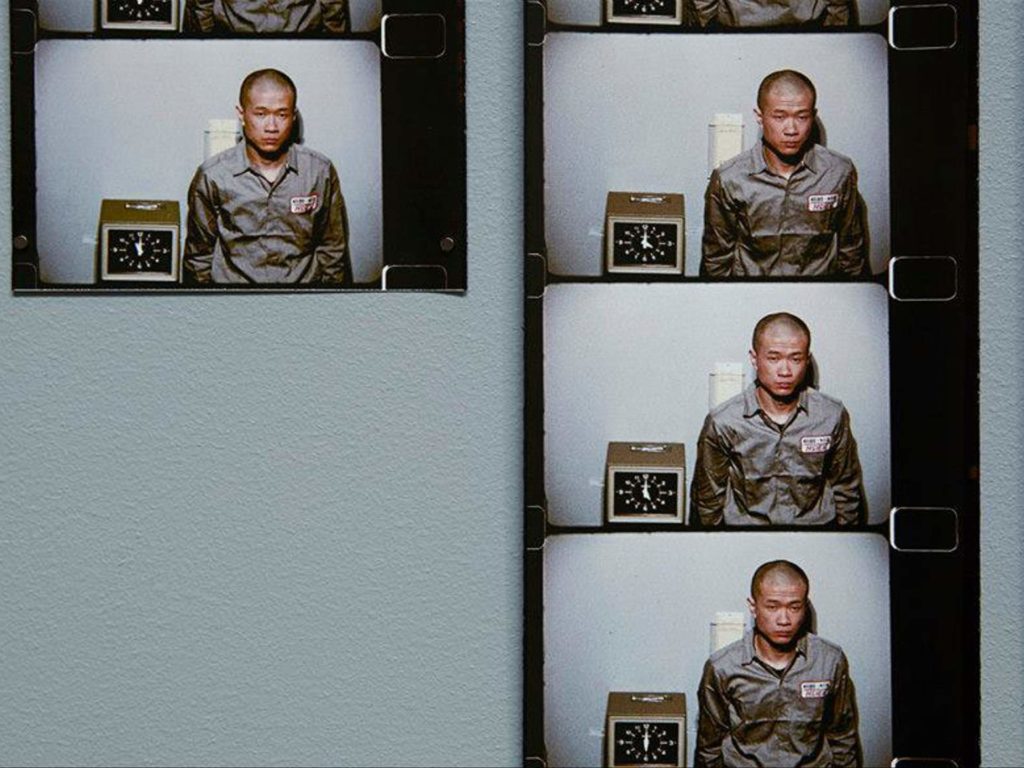

Lisa Beauchamp (Director, Gus Fisher Gallery, Auckland): During lockdown, I’ve become increasingly conscious of time and my use of it. Often, we don’t have enough time; it seems to pass quickly. The pandemic has arguably slowed down time and increased restrictions pressure us into a subservience to it. As news changes by the hour and extended isolation take its toll, I have thought a lot about durational performance and an incredible work by Tehching Hsieh called One Year Performance (1980–1). For a whole year, Hsieh punched a clock on the hour every hour. He never slept for more than fifty-nine minutes for a whole year. Inconceivable, crazy, timeless?! In this epic work, Hsieh focuses purely on the nature of time when all activities are controlled by the clock and the restrictions placed on himself as an artist committed to the production of a performance dominated by and about time. In this current context, where the pandemic has threatened everyone’s daily routine, I think Hsieh’s work warrants renewed attention as we all encounter and become acutely aware of the experience of time itself.

Martin Patrick (Martin Patrick Associate Professor, Whiti o Rehua School of Art Massey University, Wellington): Korean artist Nam June Paik’s Good Morning Mr. Orwell (1984) was an altogether ambitious effort in video art—a field which had often involved tiny audiences, guerrilla television, and the handing of videotapes between artists as if some unusual form of contraband. Following up on the implications of his previous works, notably his psychedelic montage of appropriated and newly conjured imagery Global Groove (1973), Paik transmitted a counterargument to George Orwell’s dystopian literary vision live by satellite to twenty-five million viewers on 1 January 1984. A kind of arty variety show featuring ‘everything from rock-and-roll to comedy to avantgarde music and dance’ according to host George Plimpton, it reputedly suffered from many technical glitches, making it function less than smoothly. The residual footage of Good Morning Mr. Orwell offers a rather awkward time-capsule compendium. Nonetheless, I think of such aspirational and idiosyncratic efforts by the artist who coined the term ‘information superhighway’ as curiously resonant with our current moment. Paik’s early gestures included cutting off composer John Cage’s necktie and dragging his own head along a strip of paper to paint a line. He was an artist fascinated by embodied, performative physicality, and, via his collaborations with musician Charlotte Moorman, the intimacy of touch. But as we are Zooming our spectral visages around the globe at the moment, perhaps it’s an opportune time to give a little acknowledgment to a most prescient technological visionary and his onetime effort to link the globe.

Next week: Christina Barton, Helen Hughes, Allan Smith, Lara Strongman, Joel Stern, and Peter Shand.