Film historian Thierry Jutel on Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film Weekend. Jutel introduces a screening of the film on Sunday 16 September at 2pm.

Watching Weekend in 2018 tells us what the forthcoming social and political upheavals of 1968 looked like from the perspective of a key figure of world cinema at the time. Jean-Luc Godard was a director who fashioned his films both as commentaries on the present and as parables of the future. Weekend invites us to think about how we might imagine the transformative aesthetics and politics of our times.

By the time Godard directed Weekend, he had become one of the most important, sought after, revered, and controversial directors in world cinema. Appropriating the historical legacy of cinema and experimenting with its narrative limits and its relationships with politics, his work had come to exemplify new-wave cinema in Europe and around the world.

From his first and most well-known feature film, Breathless (1960) to Weekend, Godard directed fifteen features and seven short films. With this prolific output, he investigated the everyday and the city, the transformation and modernisation of French life, youth culture, consumer culture and politics, gender relations, cinema as art and its relation to other arts, and cinema’s present and future. While he relied on ever-present collaborators, he turned down Hollywood offers and found ways to alienate his most fervent supporters. His search for a cinéma engagé (a politically-committed cinema) saw him pursuing philosophical, sociological, and ultimately political causes in an ever-changing and progressively despairing cycle.

Weekend was made right after La Chinoise (1967). La Chinoise is a film with a political message, which nonetheless treats Maoist thought—and, by extension utopian all political commitments—with humour and detachment. Rather than forewarn the arrival of the 1968 upheavals in France, the film seems to announce the post-1968 era, that of the disappearance of belief in the revolution. La Chinoise is rejected by those it portrays; the extreme left sees Godard as a bourgeois director who has failed to commit to the cause of the revolution. He’s both puzzled and hurt by the snub of those he wants as allies. The right sees pretence and irrelevance: there will be no revolution, they think.

Weekend—‘a film adrift in the cosmos’ and ‘found in a dump’, as intertitles announce in the opening moments—concludes Godard’s first cinematic period and announces at its conclusion the ‘end of cinema’. Godard went underground after 1968, in part to escape the fact that ‘Godard’ had become a character, an auteur, a figure of contemporary cinema he did not want to have anything to do with. Godard is now ready to stop épater les bourgeois (shocking the bourgeoisie) and to turn to making non-commercial and militant films. Weekend is his parting shot.

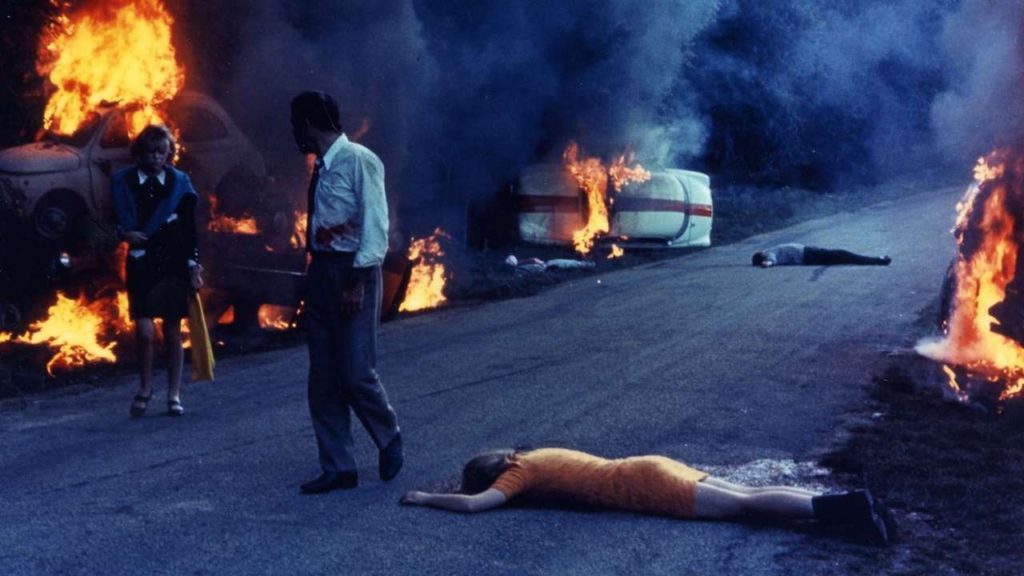

Weekend has all the convictions and intensities of a farewell statement. The film takes the premise to its radical and misanthropic end: society collapses into a post-apocalyptic nightmare in the form of pop-art agitprop. The short description of the film Godard provides the Centre National de la Cinématographie is: ‘By following an upper-middle class couple on a road trip, I would like to show all the perversions and all the dysfunctions which result from the collective hysteria which strikes Parisians when behind the wheel of their cars from Friday evenings. All their humanistic beliefs are sacrificed at the altar of the tyrannical God of leisure time.’ At the centre are two contemporary stars of French cinema, Mireille Darc and Jean Yanne, who represent a self-satisfied France, whose Anglicised and Americanised tastes speak of nouveaux riche opportunism. The title, Weekend, is a new word in French society. Godard despises what the word and the film’s characters represent and it’s hard to find redeeming qualities in them.

The film is structured around four tableaux in the form of sequence shots, whose directorial brio Godard undercuts with Brechtian slogans and distancing devices. One of these—a traffic-jam/end-of-the-world sequence—is among the most famous in the history of cinema. It is both entrancing (it looks uncomfortably realistic) and alienating (it defies our image of social civility and benevolence). Godard takes the premise of the journey into darkness to its logical extreme. Weekend has not lost any of its discomforting edges and while it speaks of its times, it reminds us of the uncomfortable synchronicity of utopian beliefs, hope, despair, and violence.

—Thierry Jutel

Thierry Jutel is an Associate Professor in Film at Victoria University of Wellington.