Joel Sherwood Spring is a Wiradjuri man working in architecture, radio, art, and activism in Sydney. His video installation Hearing, Loss (2018)—in our recent show Eavesdropping—peers into his ear and his mother’s, while they discuss her work in Indigenous health care addressing otitis media (glue ear).

Ana Iti: Can you say a bit about your mum, Juanita Sherwood.

Joel Sherwood Spring: She’s an academic working in Indigenous health. She’s currently Associate Dean (Indigenous Strategy and Services) in the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the University of Sydney. She started as a district nurse in Aboriginal schools in Sydney, in Redfern and Alexandria. She used to hassle kids to get them onto a bus to go to the doctors to check their ears. She tried to hold the services to account, because there was a happy ignorance not only among the white health providers but also among some of the Indigenous services. She was a loved and hated figure in the community. She saw that health research could benefit communities. She realised that, to get something substantive done, she had to do research—to put down the numbers to make a case for change. When I was eight, we moved to the Northern Territory for her to do her PhD research on healthcare in rural communities. Decolonising healthcare—that’s what she’s been doing her whole life. She’s an incredible woman. She’s done amazing work. Of course, the story is not just hers. There was a network of black women—nurses, mothers, and teachers—involved.

In Hearing, Loss you interview your mum about otitis media.

Aboriginal kids in the desert with glue ear—it’s a quintessential image, embedded in Australian discourse. It’s been stigmatised as a rural problem, but, in the cities, we are prone to it too, because of socio-economic factors.

Structural racism!

Exactly. But, if you’re in the city, it’s supposedly inauthentic—it’s not your identity. And yet it’s happening in the city as much as in the bush. We’re susceptible and we need to talk about it.

Was it hard to interview someone so close to you?

I had to learn how to interview someone I knew, because there’s all that assumed knowledge. What questions do you ask your mum, who has already told you these yarns repeatedly? I could have formally interviewed mum, but someone else can do that. Actually, she just did a radio interview with the ABC last week.

How did you shoot it?

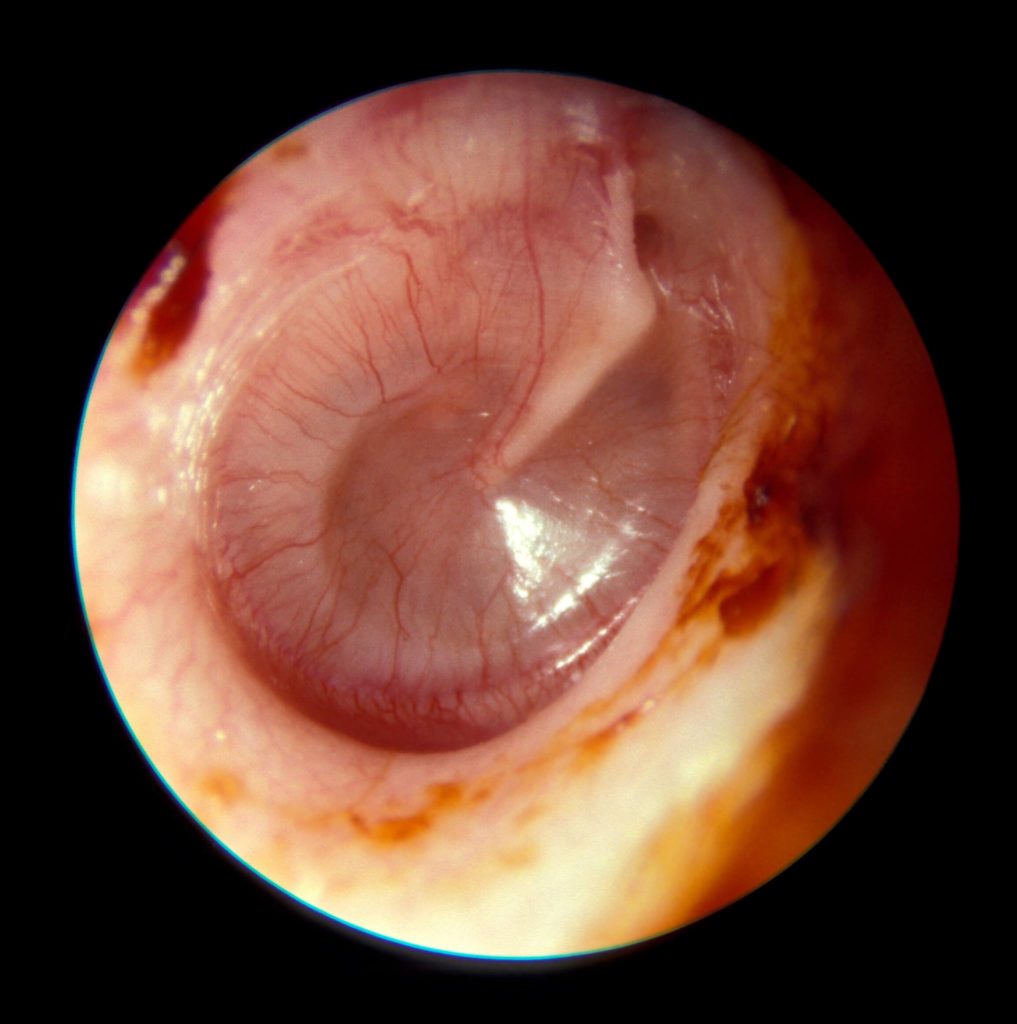

I needed an otoscope, a camera for looking into ears, but they’re expensive, $1,200, so I built one out of an LED light and a four-megapixel digital-camera part. It plugs into a USB connection to record. I had the camera in my mum’s ear, then in mine, and we were going back and forth, rehashing. It took a few hours.

When I think about the work, I think about the ear as a landscape. The big conversation for us here in New Zealand is about land rights. In this way, the ear is like a landscape that has been colonised.

One-hundred percent. The language is generated in the relationship between the people and the land. Colonialism is about the control of resources, and listening—the ear—is a site for that control. The work is about listening and language as fundamental to our culture—the oral nature of the way we pass down stories and histories.

Language comes from land. You have language to describe and communicate the land and the seasons. Language and country are intrinsically linked.

Exactly. In Australia, the history of occupation is based on land ownership. The ear is a site of mediation between the land and people.

Did Juanita show you how to perform the ear check first? Was it a choreographed video?

In a way. We staged a few iterations of the same conversation, playing with the structure of the interview.

When I first saw it, I thought it was a one-sided conversation, Juanita speaking and you listening. But we see both your and her eardrums vibrating, listening. It’s very intimate work.

We had to clean our ears beforehand, so there was no wax obscuring the view and you could see the relationships in the ear.

I wanted to relive the intimacy of the ‘ear chat’, which was a regular occurrence in our house. Mum being a nurse, she took her work home with her. Obviously we were healthy and doing the right things.

You host Survival Guide, a show about Redfern on Skid Row radio. Why is Redfern important?

In 1967, after the census and after the missions closed, Indigenous people flooded into the city for work in the factories around Redfern. Redfern was built around community services. The walk-in legal and health services that started there went on to inform programmes across the country, not only for blackfellas, but for white people as well. I went to an indigenous-kids kindergarten, Murawina, where I was taught about Aboriginal culture and language—that defined the subjectivity of my generation. The mothers and the fathers who pushed for that programme were fundamental.

There’s a language-immersion preschool here, kohanga reo, which serves a similar purpose, looking after language and community.

Survival Guide is about centring Indigenous perspectives in the conversation about selling public land and shifting public housing into private housing. It links gentrification and colonisation. I co-host it with Lorna Munro, who still lives in public housing with her son in Waterloo. The show is talking for two hours straight. Occasionally we cut to music when we’re getting sad or angry.

Lorna and I grew up in the same community. Her mum and her dad are staunch south-east mob, who’ve been embedded in the community for a long time. Her father was one of the founders of the legal service. They’re important people. We met when we were both involved in the Waterloo public-housing group. I had no radio experience whatsoever.

For the first season, I was paid by the University and I was trying to sound like an academic, but it didn’t work. Lorna and I would be saying the same thing in different ways. She’s articulate and intelligent and doesn’t need me parroting back to her in more complex language all the time. So, after the first season, we changed the structure. We’ve just finished the second season. Our show was originally the noon-to-two Friday slot. Now we’re expanding to take over the whole of Friday.

All Friday?

Not us, personally. Lorna’s been taken on as a staff member to coordinate more blackfellas on Fridays. In the last six months, there have been interesting programmes that have got lots of younger, more diverse people onto the air. We’re seeing the culture change.

The second season culminated in an archiving project in the Redfern community. Lorna and I set up a space there. The services, especially the medical services, still exist, but the communities are drying up and dispersing with gentrification, spelling the end of funding. But, for the moment, there is an opportunity to tell the Redfern story—it needs to be witnessed—and other agencies are not going to tell the story like us. We were looking to run programmes and talk back to the community about re-articulating the logic of Department of Housing planning, as well as having an outreach space where people could talk about their issues. We reached out to people who are still around or who have been moved out over the last twenty years to share photos.

We received so many calls to pick up boxes of photos from aunties and uncles, and we scanned them. We put up the images in our space in Redfern. Funnily enough, it was located just between the two medical services, so it was sort of a thoroughfare. We got a lot of aunties and uncles coming through. We put up hundreds of photos of the 1983 marches around the land-rights bills. I built a table out of materials from Redfern and Waterloo demolition sites, as a reminder of those spaces. People came in, sussed it out, and had a chat. ‘I went to school with them.’ ‘I know your cousins.’ That sort of thing. We created a space where people felt comfortable to share their concerns about the way the community is running some of the services. It was a little bolthole where you could have those conversations.

And Skid Row is different?

The station is getting lots of young people involved. At the beginning of last year, it paid a group of young people who identify either as Indigenous or black to do workshops. It turned into three or four shows. That wouldn’t happen at other community stations, like FBi, where you have to be an intern for like six months. Instead it was like, ‘No, we’re going to give you a crash course on how to do this shit.’ We don’t need it to be polished. It’s the diversity of the shows that are coming out that counts.

—

Ana Iti (Te Rarawa) is an artist based in Te-Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, her work is currently on display in Strands at the Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt.

Joel Spring was in Wellington on a Te Whare Hēra Eavesdropping residency, supported by Creative Victoria.