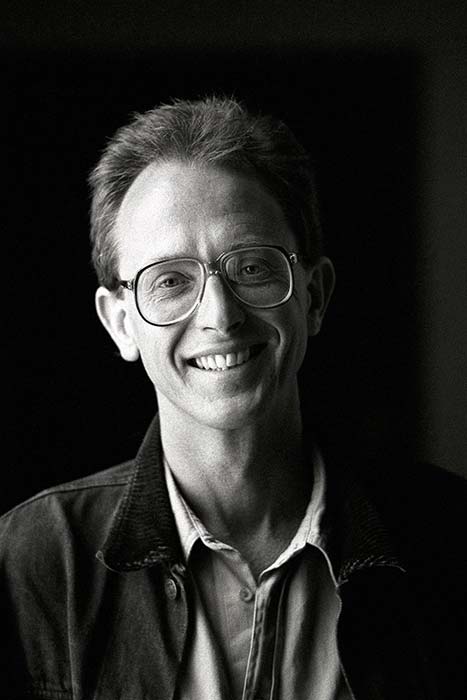

Megan Dunn interviews Ian Wedde about art reviewing.

I’ve been researching City Gallery’s past exhibitions and publishing exhibition histories here on the website. My favourite part is reading reviews from the 1980s. Lita Barrie, Rob Taylor, James Mack, and the tantalisingly named Elva Bett—their bylines ran in the newspapers of yesteryear next to old bra ads and classifieds, but their reviews are still as fresh and whiffy as the smoke from a vape—their opinions still pop. I often quote reviews to add context and colour to my exhibition histories. My most-often-quoted reviewer from the 1980s is the poet Ian Wedde. I talked to him about beginning his career as an art critic in the halcyon days when it still paid by the word.

Megan Dunn: When did you start art reviewing?

Ian Wedde: My regular gig for the Evening Post started in the early 1980s. At the time, the features room was run by a couldn’t-give-a-shit guy who had no interest in art whatsoever. The first time I took a piece in, he looked at it and threw it in the bin. He was doing one of those old-journo routines. He said, ‘Don’t expect me to edit this. For a start, I can see that it’s a good hundred words over, so go and do it again.’ From then on, I wrote the exact number of words to extract the exact amount of money I was to be paid. For the next decade, I wrote one or two reviews a week.

How did you get the gig?

I hung out in the art world and had quite a few friends in it. One day Peter McLeavey said, ‘Would you be interested in reviewing for the Evening Post?’ He put a word in for me at the paper.

Did you choose what you reviewed?

Yeah. And it was at an interesting time. During the 1980s boom, there was a shift. The dealer-gallery scene was livening up. There was a new generation coming through, and, for gallery goers, some surprising stuff started to happen. The emergence of photography, for example.

When did your interest in art begin?

When I was at college in England, I spent quite a bit of time in the art room. I had dreams that I was going to be an artist. With my pocket money, I had accumulated a kit of art tools: brushes, paints, easel, all that traditional stuff. There was this other kid in the class who I could see was really good, but he probably had a personality disorder of some sort. One day, when I arrived at the art room, he’d taken a razor blade and cut the tips off my brushes and thrown all the paint out the window into the nearby river. He completely destroyed my kit. He got punished by the school, but I thought, ‘No. You’re right. I’m wasting my time. Thank you.’

What makes a good review?

Not going in with an opinion. Go in with an open mind, first and foremost. Look at the work carefully. If you’ve been looking at art for a while, you will be informed, so you’ll probably already know the artist’s work. But every time, give them a new chance. Something unexpected is always waiting. And, if it’s not, then at least then you can go, ‘Well, this is consistent. I’ve seen this before. Here are the little tweaks.’ Talk to the artist if you get a chance.

So you’re for talking to the artist then?

Absolutely. The gallery is a social space. It’s not just a consumer space. And when you look at art, you’re in the presence of an artist as well as in the presence of the art, and that’s important.

A lot of people tell me they get fatigued by description in reviewing. Do you share that sentiment?

Reviews that merely describe are a waste of time. You have a duty to be honest about how you’ve approached the work, and how you’ve responded to it. Just describing it is lame.

Does description play a role, though?

Yes. It tests your powers of observation. Description gives the reader a chance to understand what the work consists of, how it appears, but you can’t just do a word picture of the art and sign off.

What did you enjoy about reviewing?

I always loved having an unexpected encounter. In the 1980s, I had great encounters with new work from artists like Jacqueline Fahey and bad boys like Philip Clairmont. Recent work by more established artists was interesting too. Because they’d been making work for a lifetime, it was the opposite of the shock of the new. How had they maintained continuity?

In the 1980s, there was the postmodern turn, which you engaged with—indeed typified—in your 1990 show Now See Hear! What do you make of that turn now?

It was an immensely interesting moment, which inflected and in some cases radically changed how many discipline areas engaged with their subjects and audiences—in art, sociology, anthropology, literature, and even politics. These disciplines were challenged to think and work beyond their traditional silos, to address issues of power and privilege, to read their worlds from more cross-disciplinary viewpoints or subject-positions, to be aware of the historicity of conventions. A lot of critical energy was generated, as well as a certain amount of bullshit, and both were interesting.

As an author of poetry and fiction, where did art reviewing sit in the hierarchy of your writing?

Writing poetry is nothing like writing fiction. Writing fiction sometimes gets a bit close to writing essays, and vice versa. Reviews are a very modest form of the essay. Most of my reviews were 600 words, or, if I did the weekend review, 1000. I had to be very economical.

Did people take umbrage?

Occasionally.

Physically?

Came close a few times. Understandably, a bad review can be quite hurtful. I hope I was never gratuitously mean. But it goes with the gig, doesn’t it? If you’re going to write what you think, you can expect a reaction if someone feels hurt or misread. I always had my A-line of defence: this is my view. Every so often, a dealer too would get sniffy because, of course, they had marketing issues.

Do you value reviews?

I really do. The old-school newspaper-based culture was a slower one. The online discourse now is quicker, more casual, more conversational. On Twitter, a person occasionally nails a topic in a hundred words, and that’s an interesting thing to be able to do. And then this massive response follows. Nothing like that ever happened writing for the old ink press. Every so often, there’d be a letter that the editors deemed to publish. But the art column was not a big piece of the newspaper’s business.

This is you on Tom Kreisler’s Not a Dog Show from 1987: ‘It’s the line, the drawing that makes Kreisler’s paintings go. Supple,relaxed, and unworried.’ What would get you into writing a review? What would make something ignite?

Something like that. Something that does what art should do, which is grab you in some way. Kreisler’s work has a twangy, vernacular feel about it. I was probably channelling the language of the art itself.

I think you were. Kreisler’s paintings do present as unworried, even though they worry certain issues.

Yes, but Kreisler’s voice, if you like, is pretty chilled.

And this is you on the exhibition Duane Hanson: Real People, which toured to City Gallery Wellington in 1988: ‘Hanson’s realism is really a provincial revenge. A revenge erected on high art and what it stands for by those victims of the American Dream’s failure.’

That’s not bad.

It’s pretty good, huh? It’s an interesting way to think about Hanson’s characters. I also liked your description of Christina Conrad’s work as ‘conscious primitivism’.

The first time I met Christina, she was stark naked and covered in mud, hanging out with a bunch of people who were pretty much the same.

What were they doing?

They were being primitive.

What do you think of how artists’ careers play out? You will have seen artists start with promise, then disappear.

There were always interesting start ups, and later you wondered what happened. Maybe they ran out of gas. Maybe they had kids and had to go and get a job. They couldn’t sustain their art careers. That was sad. Some became good art teachers.

Do you think the cream always rises?

No, I don’t. But a certain bloody-minded determination helps. And a bit of ego, actually. You can’t be a modest soul and survive. You have to have a bloody-minded streak to keep going.

Are you riddled with self doubt, or do you have some bloody mindedness yourself?

Oh, it’s got to be both. As a writer, if you’re totally thrilled at everything you’ve done first stroke, you’re going to be in trouble.

How accessible should an art review be?

It depends where you’re publishing. When I wrote for the Evening Post, I was writing for the people who read the paper as well as for those who were interested in art. Not that you pitch your language entirely to the publication, but, naturally, depending on who you’re working for and who you’re writing to, you need to respect that situation.

There’s a line in your essay ‘Virgil in Palmerston North’ in your book How to Be Nowhere: ‘Language … identifies the user.’

In all sorts of ways. It might identify the user as an avoider as well as a user.

How quickly would you write Evening Post reviews?

Often very quickly. I’d write notes in one of my little notebooks, go bang it out, and take it into the newspaper by the deadline.

So, a few hours?

Maybe not even a few. There was a connection between it being a well-paid gig and having a deadline. The newspaper liked reviews done on the evening of an opening, if possible. So there was a real discipline around getting it written in time. It paid properly back then.

What were you paid?

About a dollar a word. And a dollar was worth more in the 1980s than it is now. The weekend paper was more like two dollars a word. The Evening Post gig was among the things that I lived on. I couldn’t do it now.

No, it’s a very different landscape now. What makes someone a good art critic?

You have to be engaged with it. You have to be looking.

Criticism, funnily enough, is somehow founded in enthusiasm, isn’t it?

It has to be. You have to be riled up, in love with it, or bored to death. But you can get jaded. When you don’t feel honest in what you’re doing, you should quit. For a while anyway.

That’s what you did isn’t it? I read this line in ‘Bad Language: How to Start Writing Again’: ‘I was recycling a very limited store of ideas.’ Is that why you stopped?

Pretty much. I just thought, this is rubbish. I stopped review writing because I began to feel it was fraudulent.

How natural was your transition from art reviewing into curating?

Fairly natural. When I stopped writing, I had the chance to work at Wellington City Art Gallery. I was involved in a couple of big collaborations, including Now See Hear! (1990), which I curated with Gregory Burke, and a couple of Festival projects. Then more opportunities began to roll out.

Becoming Head of Art and Visual Culture at Te Papa was obviously a big appointment. You got a lot of flak.

Oh, I did. The Parade exhibition crossed a few lines because it was open to every possible way of looking at art. It was a revolutionary project in every sense—it even had an airplane and a motorbike. But it hit nerves in the art world, including those of some Te Papa board members who were also art collectors. The chairman Rod Deane went ballistic. And I thought, great. If you want to see an art project that truly crosses the line and stirs up shit, then it’s not going to be the latest high-end contemporary-art show, about which you will hear nothing. I was a big supporter of Parade. But it had ergonomic issues and the recipe was just that bit too rich. Then, I got the job of doing a kind of sanitised version, which became acceptable enough, but wasn’t nearly as interesting.

And Te Papa has been criticised ever since.

Well, it’s a high-profile place. If you’re going to stand up in public and make some noise, you can expect to get push back. The challenge thrown at Te Papa was: you’re too loud, too noisy, too messed up, too hands on. But I watched the crowds going through there for over a decade and it was phenomenal. Jock Philips’s history exhibitions were very good too. They were hated by academic historians who said they were oversimplified. But what are you supposed to do when you have families coming through with tired kids? Make it really hard? We had to argue for devoted kids’ activities. The board didn’t want them, but they were great.

Looking back, what was the role of Wellington City Art Gallery.

It played a very important role. It sustained conversations with the art world outside New Zealand, bringing in ideas, artists, and curatorial conversations. It was the most important space in building relationships outside New Zealand. The projects were a mixed bag, but that’s to be expected.

In the late 1980s, Greg Burke started as the Gallery’s first dedicated curator. Public programmes started to thicken. And there were other critics commenting, including Lita Barrie.

It was pretty lively.

It reads lively. Lastly, is honesty is the best policy?

You have to temper it with good manners, where necessary. But if you think the artist or exhibition is really deserving of a good whack, then you should do it. I don’t think I wrote many of those.