Patrick Pound’s speech at the City Gallery Foundation launch of On Reflection, 10 August 2018.

Whakawhetai nui. Thanks very much.

First of all, I want to acknowledge the Foundation members and thank them for their support of the Gallery and all it does.

On Reflection shuffles my collections of found photographs and found things with the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa’s collections.

I collect things in categories from ‘photography and air’ to ‘photographs of photographers taking photographs’, from ‘things that hold an idea of air’ to ‘things that hold an idea of falling’. I have collections of ‘photos of photos’ and ‘photos of people holding photos’. I have collections of ‘photos with the photographer’s shadow caught in the picture’ and of ‘photos of photographers caught in their car mirror’.

The show is organised as a vast palindrome or Rorschach test, playing on ideas of mirroring and ‘the double’. You have to enter in the middle and then go either left or right. This show will definitely divide people. Whichever way you go, it’s all the same to me. The show is arranged as a vast, symmetrical puzzle, where each collection is mirrored by a corresponding collection on the other side. I thought it was a great idea until we had to install it. I’d like to thank Nick Banks and his team for their patience and skill in this immense task.

This show is about noticing things and the connections between things. In it, you’ll find a pairing of paintings where one (a Louise Henderson still life) can be found repainted in the background of another (Rita Angus’s portrait of Helen Hitchings). My work treats the collection as a medium. For me, to collect is to gather your thoughts through things.

I want to unpack the museum and give its collection objects a sabbatical from their usual task. Museums collect things as exemplary objects. I collect things that are exemplary of my ideas. The collection, then, is my medium, of sorts.

Museums typically turn things into signs of themselves as they are set the task of being exemplary. That is, they are turned into typical and excellent examples of a certain type of thing. Museums becalm things. Take a Jacobean wine glass that’s been bought by a museum to be a sign of a peak of the craft of air-stem glass blowing and of the class politics and lifestyle of Jacobean England. That wine glass is never going to hold wine again. God forbid. But, if I take it and put it in the Museum of Air, it asks us to rethink it in terms of the air in its stem—the fragile breath of its maker caught 400 years ago, until someone finally breaks it. Things don’t get a say in this, of course. That Jacobean wine glass must be getting bloody thirsty by now.

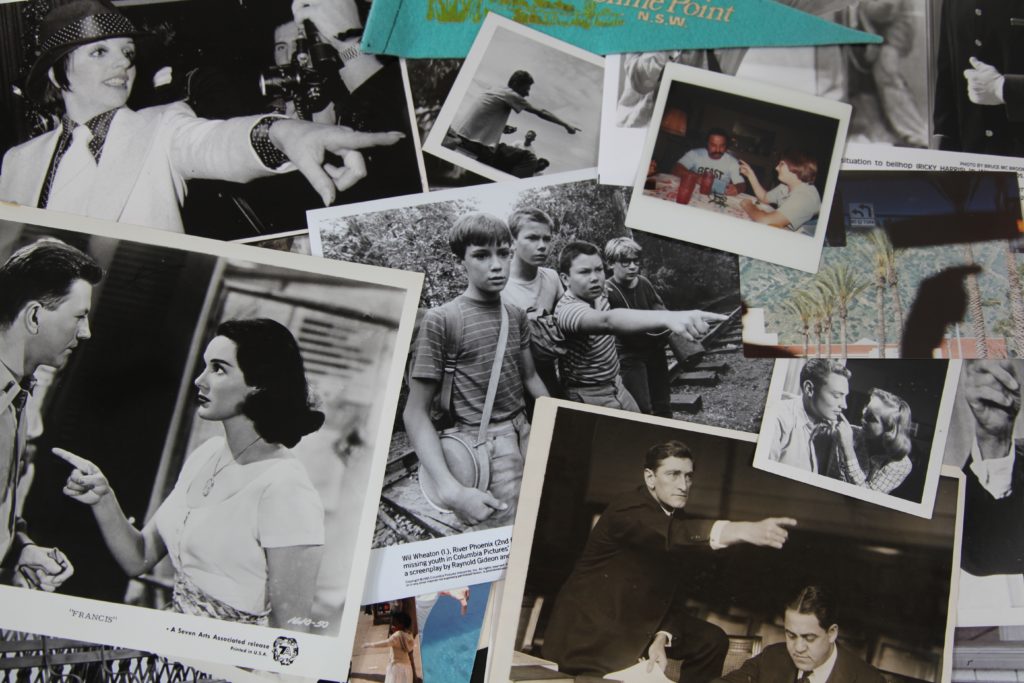

Drink as fast as you can, as you aren’t allowed drinks in the show. When you have finished drinking, at each end of the South Gallery you will find The Point of Everything. Art is a modest game after all. Each thing is found to hold some idea or other of pointedness. Some of the Te Papa objects and my things are pointy, others illustrate the act of pointing. Some are harder to work out just how they belong in this temporary collection. Your job is to find the point in everything in this collection.

You will be relieved to know, all the puzzles in this exhibition are solved for you. Your task is to work out how the things belong in each collection. Your task is to test your wits against my collections. It’s part detective story, part garage sale.

One Te Papa painting in my The Point of Everything collection seems, at first sight, to have nothing to do with pointing at all. However, it’s actually by an artist by the name of Poynter—spelled with a Y. You see the searching and sorting of things is always surprisingly arbitrary. My work redeploys Internet-search and the museum-catalogue strategies as puzzle-setting and puzzle-solving devices. It’s a poetic form of tragicomedy, of course.

What you also find, when you impose a particular collection constraint, is that, within that constraint, the rest of the world sneaks in. Gathering things under the category of pointing or pointedness, you get everything from a pointing angel to a teenager flipping the bird at a priest, from a feminist photograph to a three-point plug protector to the point of a corner post from the Rugby World Cup. Elsewhere, you will find other sets of Te Papa works and of my found photos that see the wind blowing left, and, then, at the other end of the gallery, the wind blowing right.

I want to put the dad joke back into conceptual art, where it belongs.

The collections in this exhibition quietly retain the patina of the techniques and habits of search engines, from the Markov Chain to the logic gate to the taste profile and so on. The Internet shows us what it thinks we will like depending on what we have liked before. That is its genius and its poetic flaw. The Internet makes sense of things via binary-logic gates such as either/or and and/or, and similar search look alikes. But don’t ever forget that heart pills and contraceptive pills look the same but they don’t do the same thing. On the other hand, some things have little in common until they come into contact. If you put two things together the world is changed. That’s why we collect and it also explains kids, I suppose.

The Internet is a vast unhinged album. I collect things in categories and things that might somehow be paired with other things. The show is made up of thousands of found photos and other things I’ve bought on eBay. There are photos that look the same from both sides. There are photos featuring the camera strap and the camera case. There are photos of people resisting having their photo taken. There are photos of the same person over many years. There are photos of the moon landing taken from TVs in France, England, and New Zealand. Apparently, the moon landing happened in lots of places at once. There are two photos of Mel Gibson taken off TV sets in different houses bought from two distant parts of the world. In both, he is being shot in the head. It was a special day when I found the second one. I considered retiring.

The show is full of coincidences, but, remember, what is really mystical is that more things don’t connect.

Jules Verne said, ‘Look with all your eyes, look.’ With my work you have to use all your eyes, but very little brain power. My work treats the world as if it were a puzzle. It seems to say, ‘If only we could find all the pieces we might solve the puzzle.’ It’s a folly, of course.

Something to remember about photographs: the camera stops life in its tracks. Sooner or later, every photograph becomes a photograph of and by a dead person. The camera is an idling hearse.

Some photos might seem a little more voyeuristic than others. Say, the collection of people from behind. You have to be careful when you are searching for those on the Internet. But nobody in the thousands of photos upstairs can see you looking at them, so take your time.

People often get a bit nostalgic for the people in the photos, who have parted from these photos and sometimes from the world. But don’t forget the photographers, who are nowhere to be seen, except of course in the collection of photographers’ shadows.

I’d like to thank Elizabeth Caldwell and Robert Leonard for the offer to make this new project for City Gallery and to Aaron Lister for being an exemplary curatorial genie. Thanks to the Te Papa team who’ve been extraordinarily generous in their engagement with this project, especially Athol McCredie and Rebecca Rice, who allowed me to hold a mirror to their collections, to see how things might be found to hold ideas differently and exactly what paired up and what might then unfold. All of you brought so much to the table.

The City Gallery curators are simply fab. I’ve known Robert for 107 years. In fact, when I was at art school in the 1980s, I came to Wellington for my first solo show and Robert turned up at the opening without any shoes on. He then spilled the gallery wine on the pile of my first-ever catalogues. We’ve got along very well ever since. Then there’s Aaron Lister, the curator of this labyrinth, who took each of my interconnected bicursal paths in his stride. I doubt he will ever want to see a found photo ever again, but I will always look forward to seeing him again. The team here have frankly spoiled me. Things have definitely moved on since my first visit over thirty years ago. This time, they’ve spilled wine down my throat, rather than over my catalogues.

I also want to acknowledge Hamish McKay. I was in Hamish’s first exhibition and he has been a great supporter and friend for over thirty years. I want to thank Melanie Roger, my dealer in Auckland, and Simon Hayman, from Station Gallery in Melbourne, who have flown here for this, for which I am most grateful. I also want to say thanks to Jim Barr and Mary Barr who’ve collected my work and tolerated my dad jokes posing as conceptual-art strategies. They have put me up and put up with me for over thirty years. And thanks to all my extended family who have made the trip.

All of these people are lifelong friends. Art is, after all, a way of living. In my case, it’s not a way of making a living.

Finally, thanks to my wife Juliet. My family have to be tolerant. Every day packages of things arrive. Every day, the house gets fuller. At night, we push some down the table to make way for dinner. Often, it doesn’t work, so I have to clear the couch. I’m grateful that I haven’t ended up having to sleep there.

I try and make connections between all these things. But the connections that count most are familial.

—Patrick Pound