.

For the third instalment of our essay series ‘Art History Is a Mother’, in partnership with Verb Wellington, we hear from architect and artist Elisapeta Heta.

.

How do you draw upon a visual history you cannot always see—that’s hidden on the edge of the city, at the edge of the library, on the edges of someone’s lips? How do you trace your ears over her songs with your mind’s eye? What do you do when your body has only a faint memory of the languages your blood once knew? Where is the straight line between birth and rebirth that affords you access to the things others have—where their faces, buildings, and beliefs are everywhere to be seen, and yours is not? I have more questions than answers. More feelings than footnotes, than textbooks, or professors, or land back.

•

I’ll be honest. I had a trigger response when I rolled my tongue around the brief for this essay and poised my fingers to write. I sat with my discomfort and realised my response would be a lament about how far and how hard I had to go to learn about my own people, to enable me to feel comfortable in the spaces I now have the privilege of occupying. Today I am able to move between art, architecture, and writing, and to find passion and ambition in undoing barriers for the generations to come.

All indigenous wāhine must navigate dissonance. Multiple, conflicting truths are held in our bodies. There are the tender complexities of things lost: intergenerational trauma seeded by disconnection from language, land, knowledge, tradition, and whakapapa. Other truths centre on the hard-earned resilience of our bodies; our healing; our hunger for knowledge, change, and safety; and our birthing new generations, not just of tamariki but of experience. And through this, one of the mechanisms that enables our resilience is our creativity—our arts.

I have heard, time and again, that many indigenous cultures do not have a word that directly translates to the English word ‘art’. The word ‘toi’ in te reo Māori has multiple meanings, which require context to activate. Toi can mean ‘native, indigenous’; it can also mean ‘origin’ or ‘source’. The reason we call carving ‘toi whakaairo’ and weaving ‘toi raranga’ is because they reinforce our connection to our identity. We commune with the world physically and spiritually through these mediums. There is no Māori word for ‘art’, I was told, because our people do not exist without the art forms that describe and embellish their lives; our art is an intrinsic extension of our ability to rearticulate our culture’s view of the world. Art is understood as life. It does not sit on the fringe of a society, but at its centre.

•

.

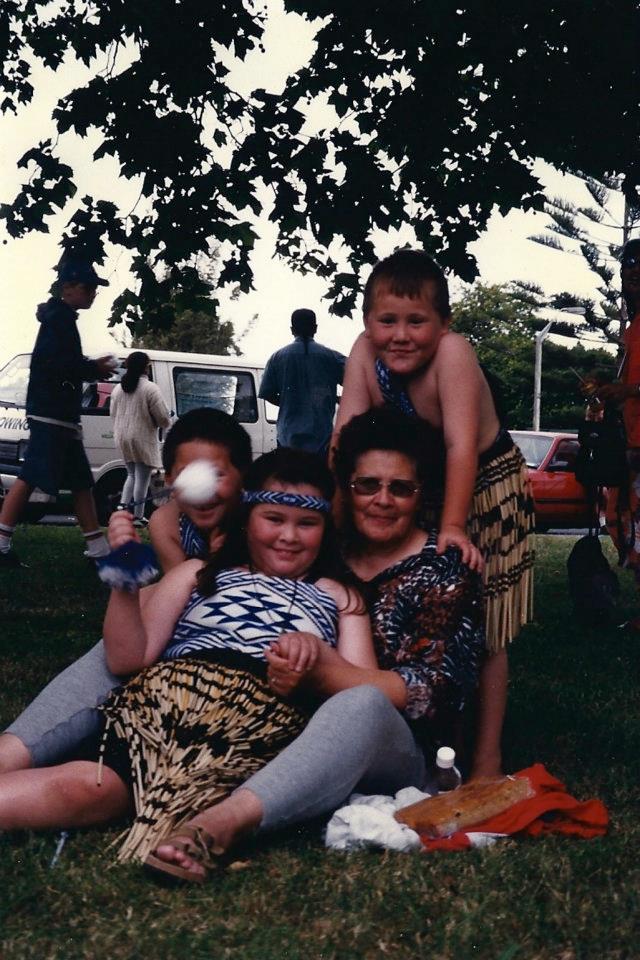

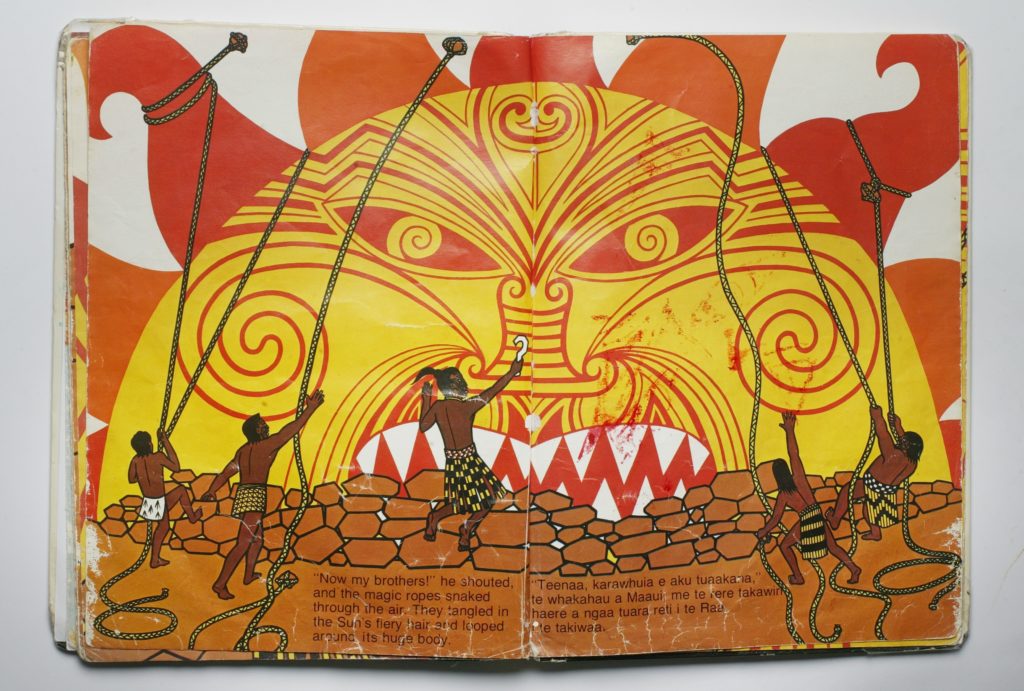

I could talk about the education system that prepared me for the world. Under the warmth of whaea Lena—and several other kui who have come and gone from my life—I had a quiet but steady hum of te reo Māori in my childhood ears. In Rānui in 1992, the colours of cuisenaire rods and the bright orange and yellow of Peter Gossage’s illustrations of Tamanuiterā being slayed by Maui to slow down our days etched themselves into my memory. I swirled koru into notebooks and paintings, and occasionally, at a tangi or on a kapa-haka trip to Koroneihana, I would see them swirling back at me. But the whaea of my little world were only able to open a small crack of light onto art forms that I rarely saw day to day. To see Māori art was more a personal fascination than public celebration.

High school didn’t teach me about art or art history. I didn’t know art was a career path or that fine arts was a degree. Art history was a correspondence-school subject, because so few students wanted to—or knew they could—take it. Plus, I couldn’t take art subjects because they clashed with ‘brainy kids’ classes. By this point, I’d dropped out of te reo Māori classes (avoiding high-school bullying). This meant kapa haka, which I’d done since I was five, was now also out of the picture. Ka kite to weekends spent under a pou, following the haehae through the haze of my tired up-since-karakia-before-dawn eyes.

In 2006, architecture school was a shock to my system. Art and architecturepapers reaffirmed white-centric, status-quo norms of beauty. We pored over Europe’s and America’s progress through its ‘isms—who doesn’t love some modernism?—with a brief stop on ‘regionalism’, where mostly white-male architects pondered what it meant to be at the bottom of the Pacific building verandas on their ‘huts’. My ears pricked up, mostly because Māori architecture and concepts of spatiality were—even if obscurely, through reference to gabled roofs—being brought into the fold of my textbooks.

This isn’t to bum out architecture school specifically. An entire education system had reaffirmed the position institutions held, where Māori history was not valued . How could you be taught about our art and architectural history, when we couldn’t learn about our history as a people?

By my fourth year (of five), I had found the work of Rewi Thompson and John Scott and was being taught by Deidre Brown and Derek Kawiti. I tapped into a vein and quickly overdosed. I began a lifelong quest to understand the intertwined relationship between ā iwi and ā hapu knowledge of te ao—the pūrakau handed down through generations as a result of this understanding—and the way it affects our language, our tikanga, our visual and material culture, and my place within this as a wāhine Māori. Realising this was the ecosystem within which my practice, my desire, and my world view was positioned birthed a sense of purpose. I found something meaty to bite into, and I haven’t let go.

•

As an adult, I liberated my unknowing from the closed, low-lit room it once lived in. I have found many ‘art-mothers’—wāhine Māori, wāhine Pasifika—for whom I have great adoration, admiration, respect, and aroha. I would like to mention some of them.

To look backwards can be painful, but it’s vital in moving forward. But there is nothing about this list of magnificent women that is of a painful, static past. They kaikaranga to us all, sending out golden ropes, vines, and beams of light from their art, drawing us into another day.

•

..

Robyn Kahukiwa

The day I stood in Ukaipō o Mahinārangi, at Tapu Te Ranga marae, with Raukura Turei, will always be a precious taonga. We were there to photograph the wharenui, as we knew she was adorned with contemporary whakairo by whaea Robyn Kahukiwa and whaea Diane Prince. To be inside—light streaming in from the tāhuhu adorned by important Māori women, with the art telling stories about wāhine atua, with the kaupapa of the whare specifically for wāhine—felt like a unique moment. The warm, soft interior held me gently, with constant song of tuī and pīwaiwaka flitting around outside. The design of the building resonated with the mahi toi to create serenity. Though we grieve for the loss of Tapu Te Ranga to fire in June 2019, whaea Robyn’s mahi remains a symbol of strength, protest, and motherhood. Whaea Robyn snuck into my childhood in unsuspecting ways. Her painting Hinetitama (1980) was everywhere, in protests, in posters, and on the cover of her book Wahine Toa, with its text by Patricia Grace. She was always sitting on a library shelf waiting for me.

•

Raukura Turei, Ngahuia Harrison, Cora-Allan Wickliffe: Sisters

.

Raukura Turei—through love and loss, grief and birth, and motherhood and friendship—has moulded a palette of earth and texture from her brush and fingertips. Through her work, Papatūānuku is a sensual being again, a woman in her skin. Raukura’s work ignites the spark of femininity that brings us all back into ourselves, our desires, our beauty.

.

Ngahuia Harrison’s lens empowers the sea to come alive. She sees our people, our whanau, and our stories in intimate detail. She is doing the hard mahi, sitting in hui after hui, living through the difficulty of how iwi were and are treated. As hard as it all is, she continues to reposition our potential—who we are and where we are going.

.

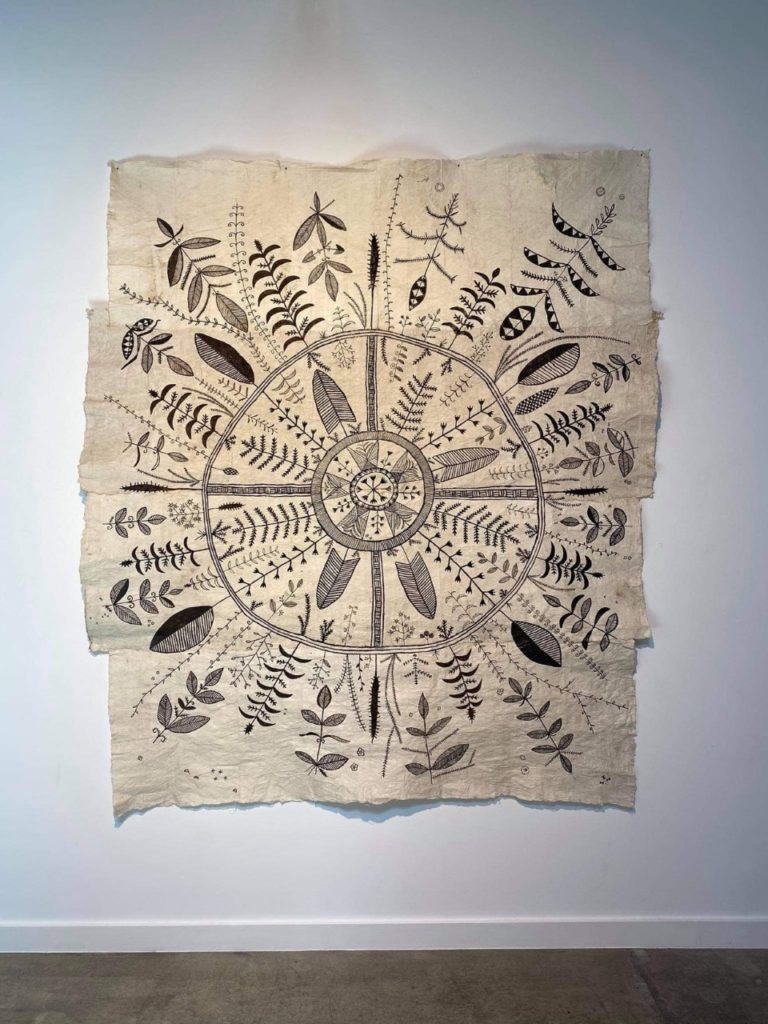

Cora-Allan Wickliffe, children on her hip and focussed, is single-handedly reviving a community and the practice of making hiapo. Every pandanas seed dipped in black ink comes away from the page having marked a story for all to soak up. We’ve come a long way from road trips to kapa-haka practice, but the goals have always been the same—an unrelenting dedication to our people.

•

.

Tessa Harris

A soothing presence, Tessa Harris is more like the water than the stone that breaks the toki (adze). A weaver and kohatu (stone) carver, she works at city scale, integrating her art into buildings, bridges, and pavements stretching for city blocks. A Ngā Tai Ki Tāmaki wāhine, mother, and grandmother, her work will live for generations to come. As mana whenua remould the city fabric to embody the bicultural future it should have had 180 years ago, Tessa is making these changes, stone by stone, pane by pane.

•

.

Lisa Reihana

I cried watching In Pursuit of Venus. Didn’t everyone? Like, full sob. I sat in the dark at Auckland Art Gallery wondering if Lisa had somehow introduced a new colour to the rainbow. You are Hine Moana, ebbing at new shores, feeling out the grit of new sands, and showing us the way. Your work stitched together the many peoples of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa and flipped the historic ramble of diseased ship captains for an account we know to be truer. And, in the way our community does when we are overseas and out and about, with your fabulous self, you are the aunty I didn’t know I needed. Big laughs, sassy advice, and dancing. ‘Cause you’re still from Ngāpuhi, which means we’re basically related, anyway.

•

.

You cannot talk about wāhinetanga without talking about Papatūānuku. You cannot disconnect the making of art from the making of life. So, I marked my own skin to reclaim my stories and my relationship to Papatūānuku. The tā moko by Graham Tipene on my forearms talks about the ocean, my whānau, and my mahi as a maker and carer. My tuālima (hand tatau), traditionally tapped with the ‘au by Tyla Vaeau, extend the mark making and the connection to place with symbols of navigation, fanau, and femininity out to the ocean, back to Samoa. And one day soon, I will mark my chin—a moko kauae not one woman in my family has worn in 150 years—to begin again our connection to who we have always been. Resilient bodies.

—

Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta (Ngātiwai, Waikato Tainui) is a kaihoahoa whare (architectural designer). At Jasmax, Auckland, she is a Kaihautū Whaihanga (Māori design leader) and a founding member of Waka Māia, a team specialising in engaging mana whenua and applying Te Aranga Māori design principles. She also works on exhibitions and publications through her personal practice as an artist. Heta has been a member of Architecture + Women since 2013, and was secretary in 2016–7 and co-chair in 2017–8. She was co-opted to the Board of the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA) in 2016 as a representative of Ngā Aho, Aotearoa’s national network of Māori design professionals, where she helped implement Te Kawenata o Rata, a covenant between Ngā Aho and the NZIA, recognising Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

.