.

The Algorithmic Impulse surveys Simon Ingram’s work over decades. The earliest work—a yellow monochrome incorporating a yellow spirit level from 1996—sets the scene, referring inwards, to itself, and outwards, to the world. The show includes Ingram’s Automata Paintings (whose gridded compositions were determined by algorithms, but executed by hand) and his Radio Paintings (created by programmed painting machines, responding to input from radio waves). The show tracks these lines of inquiry into new works: Earth Models (evolving computer models based on contrasting agricultural systems) and Monadic Device (a painting machine where human brainwaves now provide the input). Art historian Su Ballard talks to Ingram and his collaborator John-Paul Pochin.

.

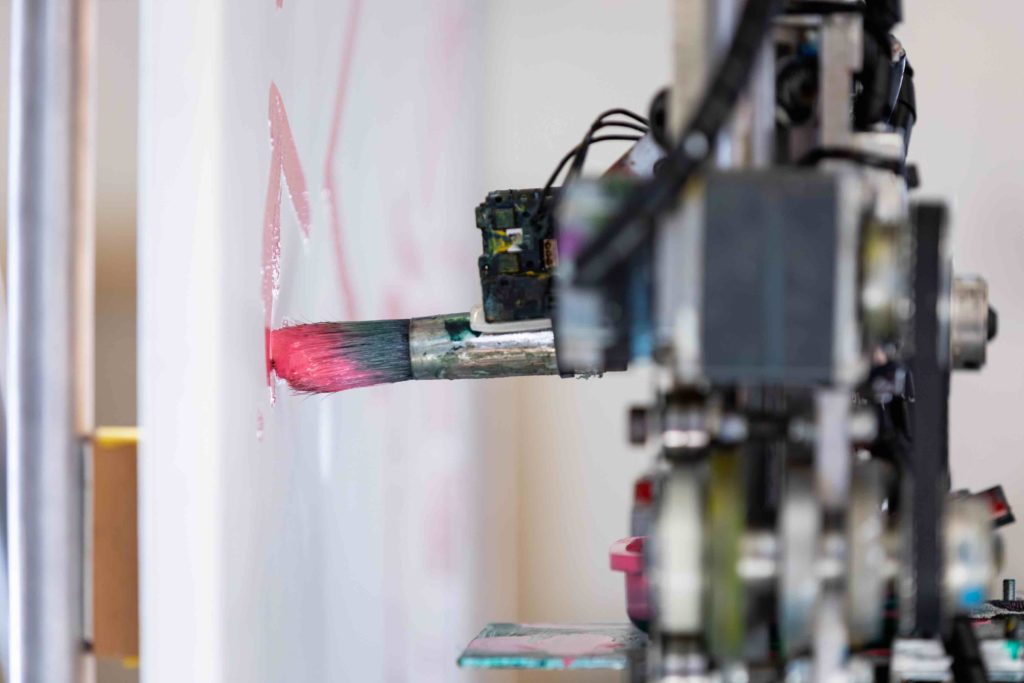

Susan Ballard: Simon, you and I have been talking since about 2011. We started off by talking about your Radio Paintings. Here, at City Gallery, these paintings are shown separated from the painting machines that produced them. They are removed from the process of their making—which is, of course, how we are used to seeing works in a gallery. Back in 2011, I remember I had questions: What’s the works’ relationship with very-low-frequency radio (VLF)? And is there science here? Actually, my first question was: Are you just faking it all? Are you just pretending that you used a machine?

Simon Ingram: It was probably less a matter of faking, than of being an amateur crossing over into disciplines I wasn’t trained in. I got interested in VLF as a way to engage my painting with the world. VLF is around 10 to 25kHz with wavelengths several kilometres long. It’s part of the electromagnetic spectrum that’s used in underwater communication between naval bases and submarines. I developed a coil-type antenna and a custom radio receiver to tune into VLF communications. I was interested in how variations in the Sun’s energy, particularly with solar flares, affect VLF communications on Earth. Later, for shows at the Adam Art Gallery, in Wellington, in 2012, and at ZKM, in Karlsruhe, Germany, in 2017, I adapted the machine to make paintings in response to spectral emissions from atomic hydrogen in the giant dust clouds in interstellar regions. These spectra—known as the 21cm wavelength because of the distance between peaks in the waveform—are observable here on Earth and are a subject of interest for amateur radio astronomers. These waves may have travelled millions of years through space, so, to observe them, is to look back in time.

Su Ballard: What does all this mean for the paintings?

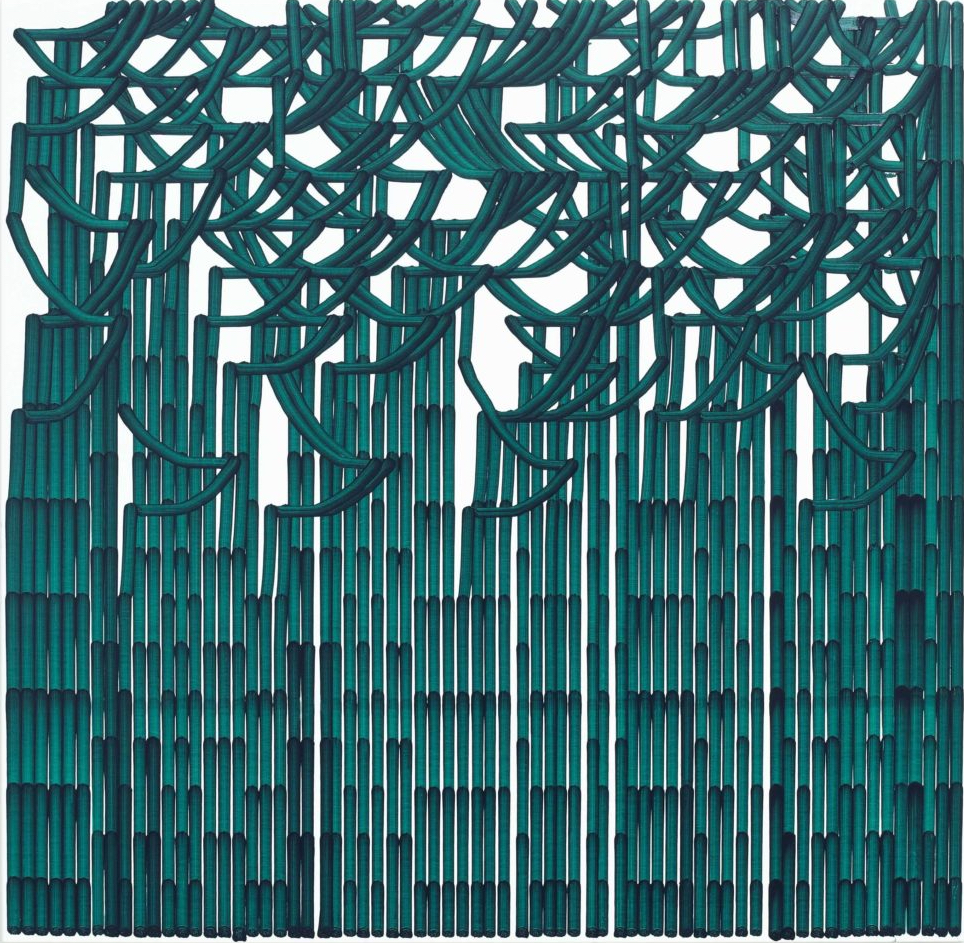

Simon Ingram: They express fluctuations of energy across a spectrum and they do this in different ways. We can see where this happens by looking for where the lines break out of nice neat rows and bounce around, as in the top half of Matotchkinchar (2011). With the ZKM works, lines run concentrically out from the centre of the canvas. There are gaps in the lines where energy has dropped below a certain threshold.

.

Su Ballard: Although your Radio Paintings appear to be discrete, finished artworks, they index the electromagnetic spectrum out there, a world we can’t see. You focus on very low frequencies, which are beyond what we can hear, but the planet hears them.

Simon Ingram: Electromagnetic energy is a theme that runs through the exhibition. Monadic Device (2018) uses an extremely low-frequency radio receiver called an electroencephalogram (EEG), an off-the-shelf headset that allows us to observe electrical energy from a subject’s brain. Hyperspectral Camera (2020) observes electromagnetic energy as both visible light and as invisible infrared.

Su Ballard: I remember visiting your studio in 2011. Your machine started painting, but you said the result was ugly and stopped it. When did you feel that you and the machine were in sync, working with the radio spectrum, collaborating?

Simon Ingram: Probably around that time. Through a mix of painting knowledge and the constraints of the device, a language began to develop. By ‘painting knowledge’, I mean, for instance, that the width of the brush is given by the need for it to hold enough paint to travel a certain distance across the canvas before the next dip in the paint pot. That the strokes are full and hold themselves, rather than dripping down the canvas, relates to the viscosity of the paint as well as to programming the brush to wipe off excess paint on the edge of the pot.

Su Ballard: The exhibition blurb says you’re seeking to ‘displace’ the artist.

Simon Ingram: That’s a provocation. It’s more a case of extending and complicating the space between the painter and the canvas, and allowing a range of different forces, methods, contents, and cultural practices to author the paintings with me. I’m stepping back to let other things come in. I’m expanding the orchestra, rather than replacing the artist.

Su Ballard: Monadic Device is a centrepiece in the show. You and I have different reference points for that word, ‘monadic’. I assumed you were engaging with the monad as defined by the seventeenth-century English philosopher Lady Anne Conway, and later popularised by the German humanist philosopher Gottfried Liebnitz. Instead of mind and body being separate as Descartes proposed, she thought we are mind, body, and soul together, a single entity that relates to the world out there.

Simon Ingram: Mind-body.

Su Ballard: So, when I heard of this idea of the monad in your work, I thought: I’m looking at a single entity: a mind and a body modelled together. But, then you introduced me to a totally different idea of the monad.

Simon Ingram: My use of the word monad comes from the German philosopher Theodor Adorno. He argued that authentic art is a social monad, where art works’ internal formal relationships echo operations in the broader cultural-political sphere in which they’re produced, and particularly technological ones. Here, I’m also influenced by writers like Thierry De Duve and Caroline Jones. I like the idea that theblank stare and flesh tones of Manet’s Olympia are informed by the magnesium-flash of early photography, and that the telephone enabled a remote factory to produce paintings for Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Jackson Pollock’s gestures have been compared to those of a production-line worker and Frank Stella said he wanted to get the paint looking as good on the canvas as it did in the can. In such moments, painting enacts, demonstrates, or works through industrial methods. In my Monadic Device, an EEG headset—an off-the-shelf device used in meditation—allows electromagnetic energy in a human subject’s brain to be streamed to the painting machine. Reflecting aspects of technology in the culture is the monad here.

Su Ballard: Tell us more about Monadic Device and what might happen with it during the show.

Simon Ingram: This was the first project John-Paul Pochin and I collaborated on. It was first shown in Sydney Contemporary in 2018. I was given an area in the middle of a large open space, so I situated the Device in a scaffolding-cube enclosure. That’s important because it feels like a zone which people enter, sit, and interact with the machine. Over the course of the show people have been invited to engage in an activity of their own choosing while wearing an EEG headset. Electrical impulses from their brain will be streamed as an input for a system that actuates the brush to wander around a support. For The Algorithmic Impulse, I’ve invited other people to participate by putting on the headset. They will engage activities: one might crochet, one might read, one might program a computer, one might paint while the machine paints, etcetera. The resulting paintings will be displayed and the people who’ve made them can claim them at the end. Also, Moniker—a subset of the Wellington band the Phoenix Foundation—will perform as a painting is being made, with me wearing the headset, listening to them. My brainwaves will be streamed not just to the painting machine but through a MIDI application that allows the data to be sonified, becoming a layer in the music. It’s some kind of duet.

Su Ballard: We’ve been talking about the electromagnetic spectrum—waves travelling around the planet and through the universe. With Monadic Device, we’re still talking about electromagnetic frequencies and waves, but inside our bodies. Are you correlating external and internal worlds?

Simon Ingram: Monadic Device uses two different frequencies, alpha and beta waves (though we could use theta and gamma ones too). Alpha and beta waves are interesting because they measure contrasting kinds of cognitive activity. The frequency of the Earth—also known as the Schumann Resonance (7.83Hz)—is just below the alpha frequency. So, yes, there is that sense of internal and external mapping here.

Su Ballard: There are different levels of collaboration in your works. In making Monadic Device, you collaborated with John-Paul. Now, there are also going to be collaborators inside the work, as part of it—other bodies will occupy the cube. Are they substitute Simon Ingrams or just cogs in your machine—because, I suspect, they will all produce Simon Ingram paintings?

Simon Ingram: Interesting question. Clearly, a degree of alienation in painting is important to me, so we are all cogs in the machine. I’d like to think that, like me, my collaborators will become tormented painting subjects, at least for the durations of their performances (laughs). Regardless of who wears the headset, my choice of materials and the software parameters always generate a certain kind of painting. On this occasion, it’s a wandering-line composition. That look was influenced by works by the French surrealist painter André Masson from the 1920s.

.

Su Ballard: Cybernetics is a reference point for your work too. After World War II, Norbert Wiener resisted the military application of his work, but his ideas were picked up by systems theorists, who used it in their development of a contemporary concept of ecology. That’s where we get the idea that dandelions and soil are connected. For me, because of that history, the Earth Models (2020) are the logical next step in your practice. They engage with a long history of cybernetic thought, systems thought, ecological thought. They connect to our world at a moment when we are trying to engage with and understand the health of the planet. With these works, you are no longer the sole artist. They are credited to a group, Terrestrial Assemblages.

.

Simon Ingram: Earth Models consists of three open-box computers in plexiglass cases. They run computer models of plants interacting with soil and atmosphere. John-Paul and I came at the idea of creating model worlds based in rule-based systems via John Conway, a computer scientist. In 1970, he developed The Game of Life, which models a dynamic set of relationships between big creatures and a virtual computational space.

John-Paul Pochin: Two of the models show agricultural methods where fertilisers are used, and one shows where they aren’t, where it’s regenerative agriculture. You can compare the results. With the regenerative example, there isn’t as much organic matter in the ground; there are less bacteria and fungi. Here, the interaction, the symbiosis, is key. It shows that, if we just leave nature alone, things will go brilliantly. But we don’t, we end up hooked into adding fertiliser endlessly.

Simon Ingram: Regenerative agriculture is a worldwide movement. It’s being taken up in Aotearoa, where it resonates with Maori farming methods. You don’t use supplements—nitrogen, pesticides, or herbicides. You ensure the soil is not bare and has a diversity of crops. What regenerative agriculture shows is that, if nature is left to take its own course, symbiosis between root and fungi systems flourishes, allowing plants to be more efficient at carbon sequestration and for soil health to increase. It means less run-off, so farmers don’t require soil to be trucked in, and sediment and supplements don’t end up in our rivers. In Aotearoa now, many farmers want to make a transition from chemical to regenerative farming, but, as our soil has been so degraded, there’s a belief that the only way we can continue to work is by using supplements. To stop that cycle and develop regenerative approaches is scary, but the sector has to break out of dependent relationships with big agrochemical companies and banks.

John-Paul Pochin: Earth Models represent interactions in soil. Soil is so complex. To get these models doing something that is remotely similar to behaviour in real soil has been hard. In the model, there is one bacterium, but, in real soil, there are hundreds. In the Models, every cube only knows about the cubes adjacent to it, but they’re constantly interacting. The result is mesmerising.

.

Su Ballard: Simon, you hung some of your earlier Automata Paintings facing Earth Models.

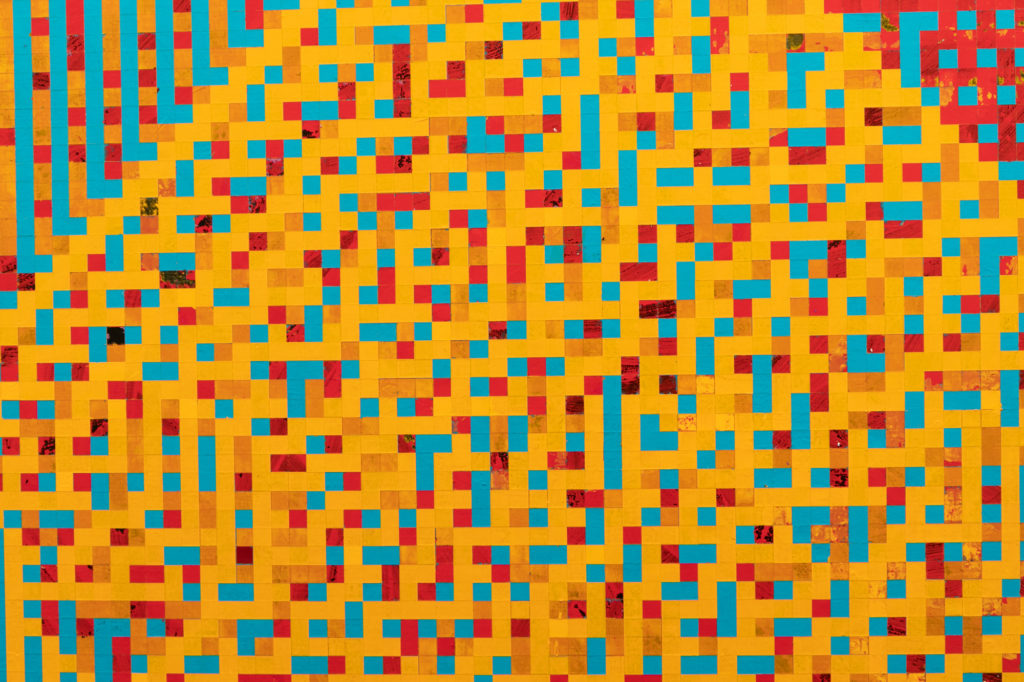

Simon Ingram: Like Earth Models, the Automata Paintings are based on game-like rules, in a framework similar to Conway’s, operating in a stepwise manner: if this square is coloured do that, if not do this. The Paintings were composed using an algorithmic system but produced manually. The Earth Models are computer generated and evolve in real time, and are much more complex in terms of their rules because they’re attempting to integrate this rule-based way of working with biological principles.

Su Ballard: John-Paul, how did you work with Simon?

John-Paul Pochin: Simon and I have similar backgrounds. Our interests in science, technology, and art mesh. We’ve both read a lot about regenerative agriculture. Simon comes at the project from painting and wanting to connect painting to technology. I come at it from physics and computer science. Simon initiated the project. He came up with the initial idea of making a series of algorithmic plants. Together, we developed this idea and the way things would look. Then I wrote the code, while he built the computers and designed their Perspex cases. Of course, along the way, ideas emerged from writing the code, from understanding what’s possible and what’s not. We also talked with others, including Shane Ward, who works in regenerative agriculture.

Su Ballard: Why produce these works as art?

John-Paul Pochin: I don’t think there’s much point in doing anything unless it’s got a message. Earlier this week, I was protesting at Ravensdown, the synthetic-fertiliser factory in Nelson. We’ve been trying to shut the place down. It’s the kind of protest where you stand under a banner or chain yourself to a fence. The flip side is this work, where we’re explaining why. That’s what the Earth Models do.

_

Su Ballard is an Associate Professor in Art History at Victoria University of Wellington. She has written for October, Artlink, Art and Australia, Art New Zealand, Eyeline, The Anthropocene Review, and Environmental Humanities. Her books include Alliances in the Anthropocene: Fire, Plants, and People (with geographer Christine Eriksen), 100 Atmospheres: Studies in Scale and Wonder (with the MECO Network), and A Transitional Imaginary: Space, Network, and Memory in Christchurch. Art and Nature in the Anthropocene: Planetary Aesthetics will be published in March 2021.