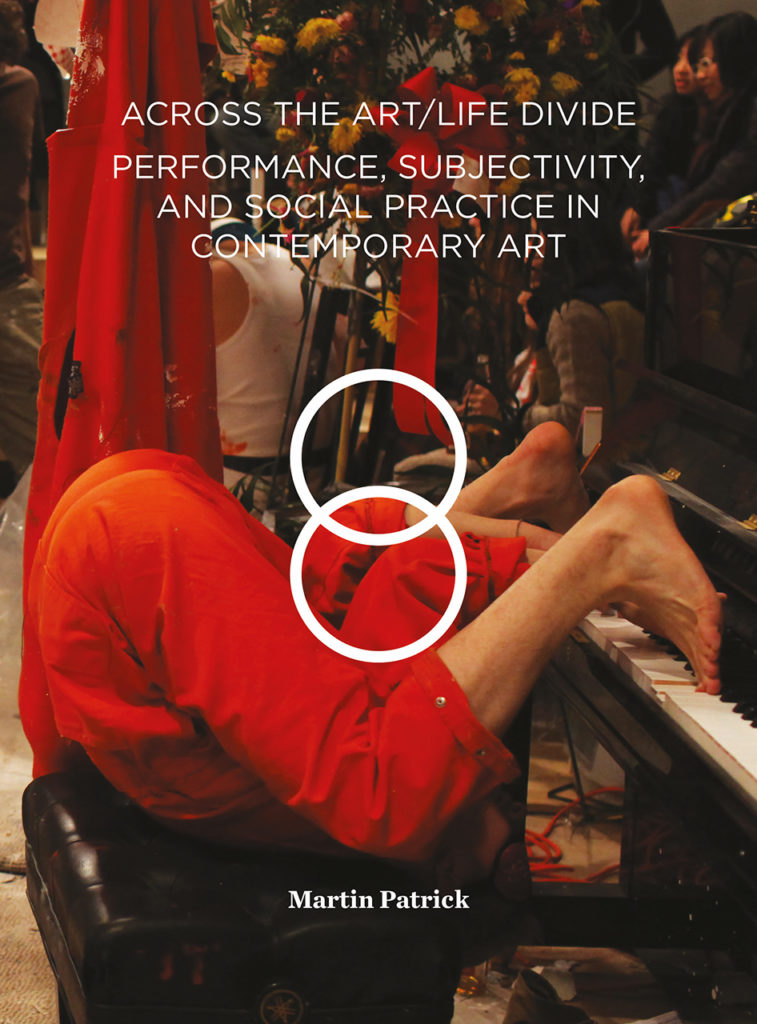

Martin Patrick is an art critic and art historian who lectures in Critical Studies at the art school at Massey University. He is a regular guest speaker at City Gallery, most recently as a keynote for the Cindy Sherman symposium. His first book, Across the Art/Life Divide: Performance, Subjectivity and Social Practice in Contemporary Art, is published by Intellect Books and University of Chicago Press, and was launched earlier this month (December 2017) at Robert Heald Gallery in Wellington. Megan Dunn sits down to ask the author some tough (and not so tough) questions.

Megan Dunn: First things first. What is the art/life divide? And how did you decide on the title?

Martin Patrick: Robert Rauschenberg said, ‘Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)’ I liked the phrase, the ‘gap between’, but the publisher thought it too opaque for a title, so we went with ‘art/life divide’. To work across the art/life divide’, artists might refer to pop culture, they might make performative gestures, they might not fit in a gallery context, or they might work a lot with their everyday lives. I quote the American artist David Hammons saying he didn’t like gallery openings because he saw more interesting stuff on the way to the gallery than when he got to the gallery itself. In the book, I play with these ideas. I address artists performing themselves, artist re-enactments and interventions, and the Fluxus ethos. And I discuss individual artists as case studies.

How long has this book been in the making?

I had the idea when I came to New Zealand to take up the Massey job a decade ago. But, as you know, various life things can get in the way. It became a long-term project.

At your launch, you quoted the artist Julian Dashper who told you when you arrived here that New Zealand artists couldn’t hate one another too vehemently—I am paraphrasing!—because they still had to attend the same BBQs.

A mutual friend, David Raskin—who had curated a large travelling exhibition of Julian’s work in the States—put us in touch. Julian gave me a colourful introduction to New Zealand art, but from the perspective of a New Zealand artist who had done many international projects and was infatuated with American art. In New Zealand, you’re only two or three people away from someone that you want to meet, but art circles run small even in big countries. The small scale here gave me the deceptive impression I could learn a lot about New Zealand very quickly, but it actually takes a long time to understand Aotearoa’s specificity as a bicultural society and the layers of history here, including what has and hasn’t been historicised.

I arrived in New Zealand as the One Day Sculpture exhibitions began, and I wrote about Maddie Leach’s one, Perigee #11 (2008). She had pinpointed the predicted date of a storm over Cook Strait and people were invited to a converted boatshed in Breaker Bay for twenty-four hours to wait for the storm—which never arrived. It was my first commissioned piece of writing on a New Zealand artist.

Chris Kraus says on the back cover that your book looks beyond the usual suspects. How did you decide which national and international artists to include?

Early on, I was researching the history of performance art, of artists living in galleries or making living sculptures. Fluxus and socially engaged art were also crucial. The curious thing is that, when you open up that art/life divide, you start seeing things you’re interested in in other genres as well. Stand-up comedians are as important to me as artists. My book represents an idiosyncratic selection of artists, but which ones are not-the-usual will be in the eyes of the beholders. For example, Ronnie van Hout, Maddie Leach, and Shannon Te Ao will seem more usual in New Zealand.

Why did you start writing art criticism?

As a grad-school art student, I realised I wasn’t much of a maker. I was more interested in the discussion and context around art works—the whys and hows. One of my tutors, Linda Montano—who is featured in the book—said, ‘You speak so well about your work you should be an art critic.’

Tell me more about the French artist Robert Filliou and Fluxus, and their connection to relational aesthetics.

Filliou wasn’t exactly a household name, although he has had some posthumous recognition. He was a communist and a member of the Resistance (there’s a picture of him holding a machine gun). He emigrated to the US, did labouring jobs, obtained a master’s degree in economics, and then worked as a policy maker. But, at one point, he decided: Enough! He chose to drop out, to be a poet, playwright, and visual artist, even though he didn’t have a lot of manual skill. He had a lot of interesting, idiosyncratic friends in Fluxus—a 1960s art movement that specialised in aesthetic non-events and looking beyond the art object. They held events like The Festival of Misfits, at Gallery One and the ICA in London in 1962. Filliou interviewed figures like the Dalai Lama, John Cage, and Joseph Beuys. In 1971, he held an exhibition titled Research at the Stedelijk, where he sat in the Amsterdam museum and spoke to experts from different fields.

Filliou worked on peace projects—always a losing battle. He asked questions like, why don’t we have departments of peace rather than of war? That sounds very hippie, but, if you look at the recent popularity of Bernie Sanders in the States, or even some of the things that Jacinda Ardern has to say, there’s been a huge shift towards ideas that earlier might have seemed like cloud cuckoo land.

The term ‘relational aesthetics’ was coined by French critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud in 1995. It has links to Fluxus and Filliou, because it shares the idea that one’s own life can be artful. Right now, many people get frustrated that art is so discursive, there’s so much talking and reading, but there’s a long history of discursive, process-orientated art.

What’s the driving question of Across the Art/Life Divide?

Chapters address different questions. Why are we looking at so much durational work now, as opposed to spatial work? Why are we fascinated by re-enactments of older art works? Thematically, the book responds to the plurality we live in, the plurality of selves we occupy. Contrary to a lot of old-school thinking, every single person in the world counts, and we’re all complex and entangled. Art is responding to this more dramatically than ever.

What will your field look like twenty-five years from now?

I don’t even know what my field is! On the back cover, there’s a kind quote from Professor Amelia Jones that says my book addresses the very question of what art today even is.

Your top exhibition of 2017?

I am going to have to defer on that one. [Martin lives to enjoy another summer BBQ.]

Modernism or postmodernism?

They’re pretty entangled.

Marina Abramovic or Jay-Z?

Tough call. Early Marina.

Colin McCahon or Gordon Walters or Ralph Hotere?

I would definitely veer toward Hotere.

Rita Angus or Frances Hodgkins?

Rita Angus.

Simon Denny or Faith Wilson?

You’ve got to redact that question!