Megan Dunn interviews novelist Pip Adam. Adam is guest host of the City Gallery Book Club for 2019 at Tuatara Open Late. She is also speaking at the opening of City Gallery’s new suite of exhibitions—Yona Lee, Cao Fei, and From Scratch.

Pip Adam is an ex-hairdresser and the acclaimed author of three books Everything We Hoped For (2010), I Am Working on a Building (2013) and The New Animals (2017)—a novel set across one day in the Auckland fashion industry. Her fiction has been described as ‘post-postmodern, confrontational, and revelatory’. In May, Adam won the Acorn Foundation Fiction Prize for The New Animals, and in her speech asked the audience to ‘please hug your hairdresser for me’. One of the prize judges, Anna Smaill, wrote in the Listener, ‘The book looks with deep seriousness at the ostensibly trivial worlds of fashion and hairdressing … It is willing to leap into the surreal in order to capture the weird violence and strangeness of being alive in this post-colonial island nation in the twenty-first century.’ The New Animals is also teeming with references to New Zealand art. Megan Dunn talks to Adam about artist Ava Seymour, fashion, and the 1990s.

Megan Dunn: An important scene in The New Animals sees photocopies of early Ava Seymour collages being passed around. Seymour’s first collages often used fetish cutouts to perverse effect. Carla’s bosses, who run a fashion label, want to ‘translate’ the feel of Seymour’s images into a men’s corporate fashion line that says ‘Fuck you’. (That made me laugh.) Which Seymour collages are you talking about in this scene? And do you know Ava personally?

Pip Adam: I was referencing her 1993 series of collages Blood and Guts in Deutschland. It’s a bit stalkerish. I’ve never met Ava. But, in 2001, I was living in Dunedin when she was there on the Hodgkins Fellowship. She gave a talk at Dunedin Public Art Gallery. I was awestruck and she became an artistic touchstone for me from that afternoon. What I respond to in her work is this puncturing of reality. She continues to be one of my favourite artists—and her work keeps making sense to me on visceral, emotional, and intellectual levels. Over the years, when I came across an artistic problem, I will often ask ‘What would Ava do?’ Which is kind of stupid because, as I say, I don’t know her at all.

The fashion-label owners in that scene quote Seymour without understanding the context of her work. What is the relationship between art and fashion?

Oh. Hmm. Good question. The Blood and Guts in Deutschland series contains some sexually explicit imagery. I’m interested in this question, ‘Why do I find photographs that are used for capitalism more upsetting than other images that are often far more explicit?’ That’s why I wanted to place Seymour’s image in that scene because her work makes the usual unusual, and once you see fashion photography as odd, or maybe as exactly what it is—using people’s bodies to sell things—you can’t unsee that. When I was hairdressing, my dad, who was an advertising man, used to say, ‘You’re selling hope, Pip.’ I’m interested in that idea too. Fashion photography is always selling a story, a feeling, an aspiration, and I wonder about art in that way.

Of course, as well as all this, I am really interested in function. In design, the object has to have a use and I love it when fashion messes with this, like those moments when skirts don’t act like skirts and shirts don’t cover anything.

I was intrigued by your reference to Seymour’s 2014 Peter McLeavey Gallery show, Interaction of Colour. It was abstract, consisting of pieces of coloured paper and was a complete about-face from her early narrative collages. In the novel, you say that exhibition ‘battered everyone who saw it’. A great mini-review.

I didn’t see the show. I’ve never been into McLeavey’s. (I’ve always felt a bit scared of going into galleries.) So I looked at images of it online. I loved it. I loved the idea of it. I am really interested in the ways we can break with narrative. I studied art history at university, and abstract painting inspired me. I think possibly I’ve been trying to remove all narrative from my work ever since.

The character Tommy keeps a photo of Seymour wearing a fur coat and aviator sunglasses on file. That classic pic of Ava seems so 1990s to me now, but, at that time, it was just cool. Still is really. What was it like trying to evoke New Zealand’s urban culture of the 1990s versus now?

I wasn’t a big ‘nature’ person as a kid. I wanted to live in a city like London, New York, or Los Angeles, so that was how I constructed my life. I tried to be in those parts of Auckland where you could see more concrete than sea. The 1990s were a hard time and I was a hard person to be around, so, in some ways, the book is an amends for that time and the people I hung around with. It was interesting to draw then and now together. My memory of the 1990s is that it felt like New Zealand was ‘getting on the map’ internationally. Friends’ bands were going to America and exciting people were coming here. However, when I look at us now, I feel like maybe New Zealand is always in the process of trying to get on the map. (I’m using ‘New Zealand’ purposefully, because maybe, hopefully, Aotearoa is a different thing to New Zealand for me.) There are people who are not ‘trying to get on the map’ and they are the ones whose work I often like best.

You have such empathy for hairdressers. I love all the detail about how to cut hair. For instance, Carla doesn’t know how to cut a ‘Rachel’, Jennifer Aniston’s ‘disconnected’ bob from the 1990s sitcom Friends. I wonder if your affinity for Seymour’s collages is linked to being a hairdresser. Snip, snip.

Oh. I like that! I have this memory of being a kid and giving the people in magazines ‘new haircuts’. I’d cut out the person and cut around their hair to make it look different. I loved hairdressing because of all that hand-eye sculpting, cutting, and reshaping. I still love cutting things out.

You’ve collaborated with photographers like Ann Shelton and written about Fiona Pardington. Is photography a first love?

I’m a bit obsessed with the uncanny and that’s what I love about photography. Yvonne Todd is another massive artistic inspiration. Bellvue (2002), her series on cosmetics-counter saleswomen, was one of the first photographic exhibitions I saw and I was floored. I’m obsessed with the way she uses commercial-photography techniques. That mash-up of the exceptional and mass production is my crack cocaine.

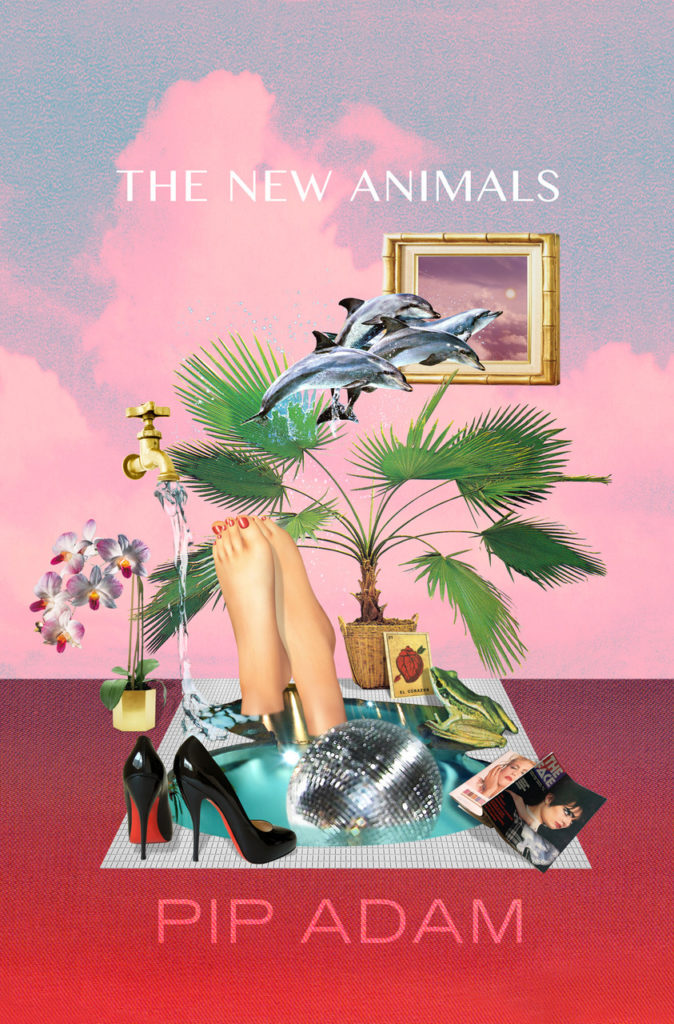

How did the Kerry Ann Lee cover for The New Animals evolve?

I first worked with Kerry Ann Lee on the Porirua People’s Library, a collaborative storytelling and skill-sharing project. That collaboration was politically and artistically inspiring. I’m an anarchist at heart. I’m committed to the idea that there is a way to live without government and without hierarchies of power, and, every time I hang out with people like Kerry Ann Lee, I am reinvigorated that this idea can come to fruition. (I get scared talking about Kerry Ann Lee like this because I think her superpower is not being the main person and I think when I talk about her I make her sound like the main person.) Kerry Ann Lee is a really talented book designer as well as an artist. She created the cover image after she read the book. It was amazing. I feel so grateful for that cover and I feel like it is a massive part of why the book was received the way it was.

The New Animals has been divisive. I loved the end and the sentences which give the novel its name: ‘… clothes weren’t right for her. They didn’t belong to the animal she thought she was. The animal she was becoming’. Elodie’s endurance swim reminded me of performance art.

Elodie is based on an artist who uses herself as subject, so maybe subconsciously that was on my mind. What happens if we interrupt something that is a convention? When we swim, we’re supposed to come back. I’m interested in art which involves the artist’s body directly. The New Animals is about the body—the limits of it and what lies beyond them. Bodies are so strange to me, my own especially.

Megan Dunn is writing a book on professional mermaids.