CURATOR Gwynneth Porter ORGANISER Dunedin Public Art Gallery OTHER VENUES Auckland Art Gallery,–

Everybody's heard about the bird. Lyttelton painter W.D. (Bill) Hammond is famous for his paintings of humanoid birds. But that’s not where things begin for this artist. Offering an overview of Hammond’s work, Twenty-Three Big Pictures links his bird-people paintings to what went before.

Hammond studies at the University of Canterbury's School of Fine Arts between 1966 and 1968. After, he works as a jewellery designer and makes wooden toys, before returning to painting in 1981.

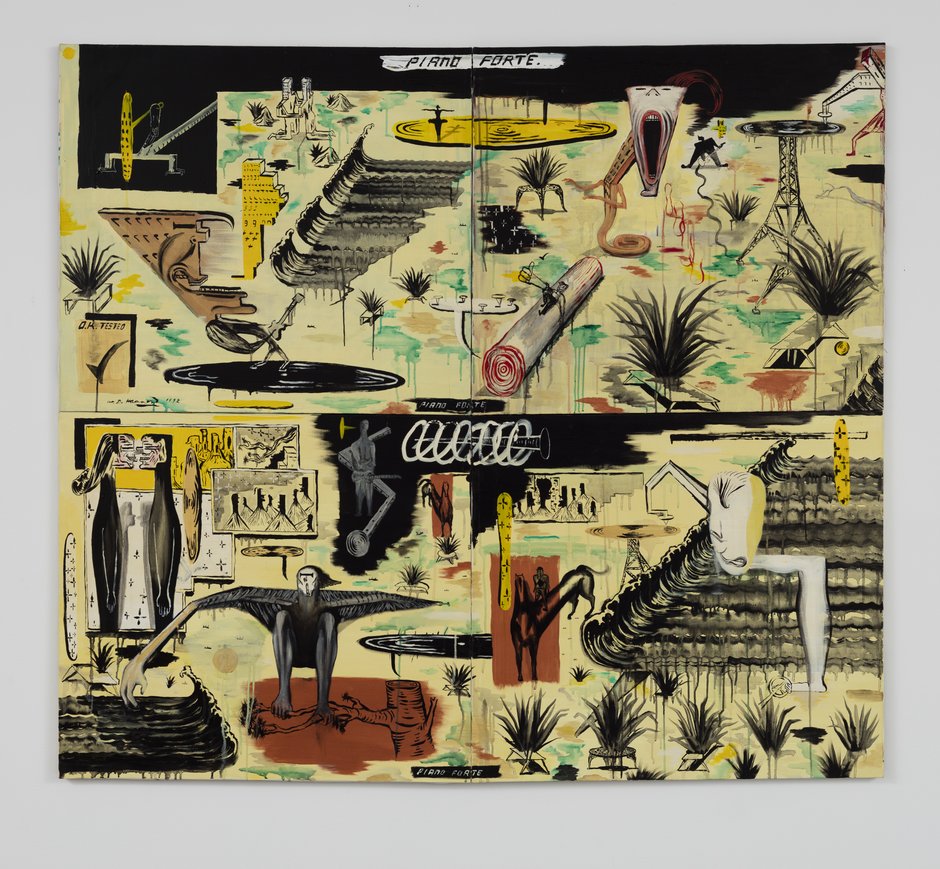

The 1980s is the era of yuppies, MTV, and Max Headroom, and Hammond channels it all in his paintings of grotesque, distorted, cartoonish figures, with their extreme, speed-freak perspectives and inexplicable, unregulated scenarios. Everything is hybrid; everything morphs into something else. Some paintings are titled after rock songs: One for the Money, Two for the Show (Elvis Presley) or The Young Designers (The Fall). Televisions and sound systems are recurring motifs.

Like his freakish, mutant, amoral cast, Hammond seems at once overwhelmed and energised by modern life, finding poetry and pleasure in alienation. Restless, voracious, he often accumulates imagery without any overarching rationale. Lara Strongman calls him a ‘pencil-case artist’, recalling the way naughty schoolboys deface their pencil cases with random doodles.

In 1989, there’s a sea change. Hammond visits the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands, where people are absent and birds still rule the roost. He says, 'The Auckland Islands are like New Zealand before people got here. It’s birdland.’ The trip inspires him to start painting the humanoid birds that become his trademark from the 1990s on.

Hammond also draws inspiration from Sir Walter Buller, the prominent colonial-period lawyer and ornithologist, known for his picture book A History of the Birds of New Zealand, first published in the early 1870s. Despite providing this beautiful record of native birds, Buller collected specimens rapaciously, in a 'avian Armageddon'. He famously believed that New Zealand’s native people, birds, and plants would be rendered extinct by European colonists, anyway.

Hammond’s paintings present his bird-people in a range of surreal scenarios. Some paintings are set in primordial nature; others find his bird-people in the pub, drinking, smoking, and playing pool. They may be ‘waiting for Buller’, but they have already adopted Pākehā pursuits.

Hammond's bird-people are wildly ambiguous. They seem to refer simultaneously to the birds that were here first, the Māori that arrived later, and the Pākehā that followed. While Hammond buys into the bicultural and postcolonial concerns of the 1990s, the precise upshot remains unclear—obscure. Perhaps that's why curator Justin Paton calls him 'the Hieronymus Bosch of Lyttelton’.