ARTISTS Julian Dashper, Luise Fong, Jacqueline Fraser, Fiona Pardington, Michael Parekōwhai, Peter Robinson, Ruth Watson CURATORS Gregory Burke, Peter Weiermair PARTNER Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt OTHER VENUES Frankfurter Kunstverein, 30 March–14 May 1995; Ludwig Forum fur Internationale Kunst, Aachen, 31 May–6 August 1995; Waikato Museum of Art and History, Hamilton, 5 July–1 September 1996; Dunedin Public Art Gallery, April–May 1997 PUBLICATION essays Gregory Burke, Julian Dashper, Luise Fong, Jacqueline Fraser, Fiona Pardington, Michael Parekōwhai, Peter Robinson, Ruth Watson

Cultural Safety is an export show—a New Zealand art show made for Germany. It showcases the work of seven artists: Julian Dashper, Luise Fong, Jacqueline Fraser, Fiona Pardington, Michael Parekōwhai, Peter Robinson, and Ruth Watson. They are young—all in their late twenties and thirties. Their work is internationalist but also self-conscious about its place of origin. In the catalogue, curator Gregory Burke writes, ‘in very different ways the seven artists in the exhibition work through an international language of art to address aspects of their local and personal situation.’ The show’s loaded, obscure, and ironic title—Cultural Safety—is a term borrowed from New Zealand healthcare, where it acknowledges a crucial cultural dimension in the treatment of Māori patients.

Cultural Safety is the culmination of a dialogue between City Gallery Curator Gregory Burke and Frankfurter Kunstverein Director Peter Weiermair. Weiermair became interested in New Zealand art after seeing Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, in 1992. He tells National Business Review, ‘I wanted to put the finger on New Zealand art and say to Germans: “Stop—have a look at this.”’

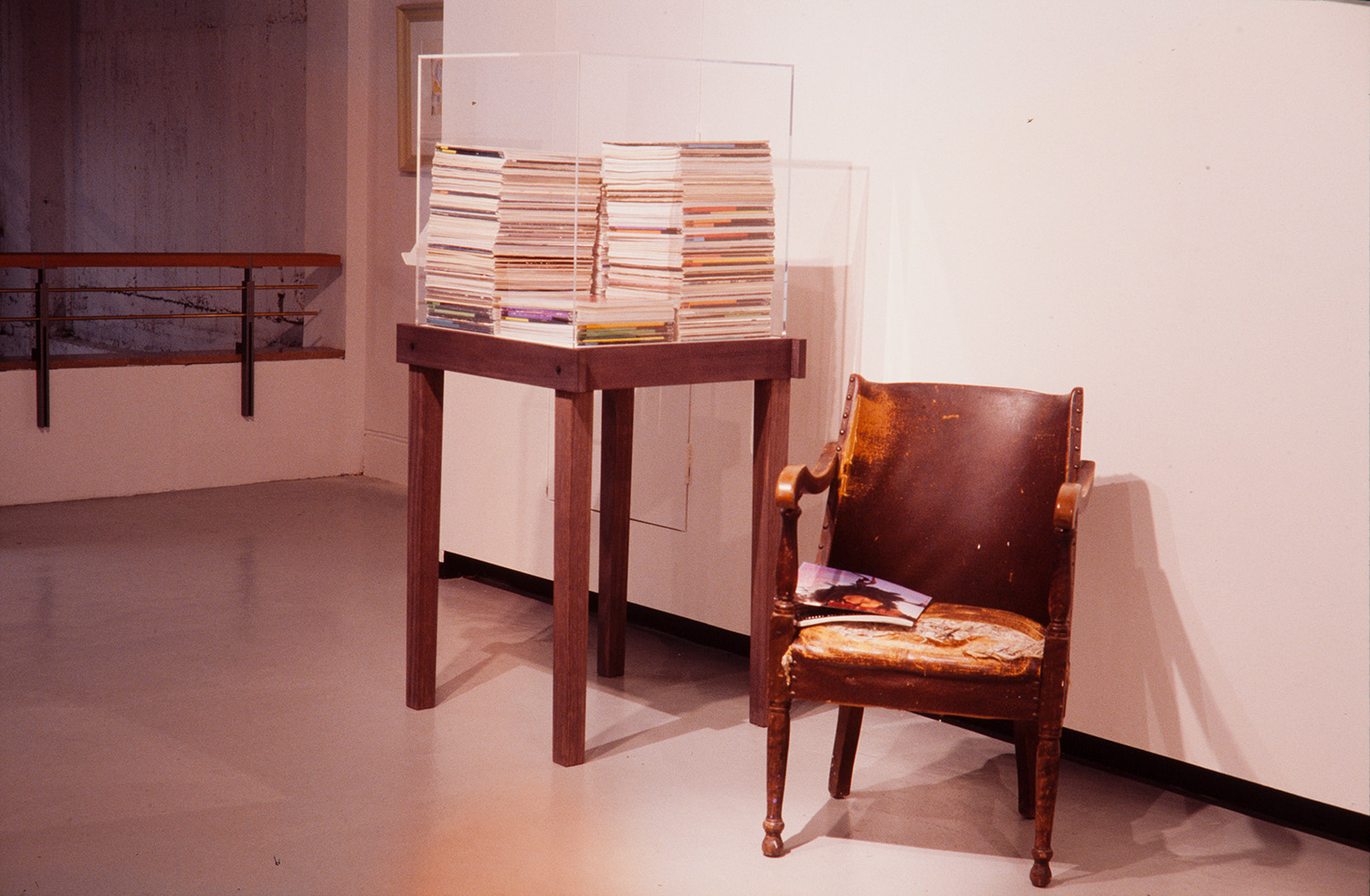

Much of Dashper’s work addresses New Zealand art’s provincial relation to the art world’s centres. He is quoted in the catalogue: ‘Images brought into this country were held up to as examples in slides. Now it seems obvious to me to start sending them back that way.’ Dashper is fascinated by the way provincials fetishise art magazines. One of his works is a project in the New York–based magazine Artforum, reproducing slides of his ‘paintings’. Another is his installation, What I Am Reading at the Moment, consisting of a well-worn leather chair and a stack of Artforum back issues. For the show, Dashper’s work is on point. Commentator Jim Barr quips, ‘You feel that if a Julian Dashper had not existed, the curators would have had to invent him.’

Tourism is a key theme. Watson’s painting Tour of New Zealand reproduces a vintage board game that promotes a white colonial vision of New Zealand. Another Map of the World is a photocopy of a map showing New Zealand as the centre of the world, engulfed by sea. Watson works with cartography, examining how our world is shaped by cultural values. By dislocating familiar things, such as maps, board games, truisms, souvenirs, and scrabble sets, Watson points to how language mediates reality. Her Souvenirs du Monde are small colour photos that mix and match knick-knacks with backgrounds—a ceramic fawn against a kitsch painting of the sea. Her Large Book is presented as a billboard outside City Gallery and features an image of an open book, its ruffled pages turning in waves, like a poster for an island holiday. A femme fatale dominates the left page, her face as unknowable as the sea. (Large Book was originally presented outside the Wellington Railway Station as part of the earlier City Gallery exhibition Now See Hear! Art, Language, and Translation curated by Ian Wedde and Gregory Burke.)

In Frankfurt, Fiona Pardington’s photographs are exhibited in a small chapel accentuating the Catholic references in her works. In this context, Veil takes on connotations of a burial shroud. Sebastian—a male nude, his buttocks and legs decorated with paper cherubs—refers to the early Christian martyr. Pardington’s dramatic black-and-white images often recall nineteenth-century pictorialist photography. She is one of a generation of women artists who emerged in the 1980s, and chose to concentrate on the photographic medium. These artists subverted the prevalent 1970s mode of documentary photography by drawing attention to the fictional and artificial nature of the photographic image. She photographs constructed ‘scenes’, and often utilises ornately decorated frames. The pair of photographs Heloise and Abelard depicts the famous twelfth-century love story between French writer and abbess, Heloise, the young student of the theologian and scholar Abelard. Their story and their passionate love letters transgressed societal and religious norms. The controversial lovers are buried together in the same tomb at Père Lachaise Cemetery. Pardington’s Choker stages another controversial seduction. This black and white photograph displays a woman’s neck wearing a chain of what could be love bites or bruises. Crimes of passion or violence? In Pardington’s photography love makes a martyr of us all.

Fong’s layered watery abstractions reference the body and mutability with titles like Pathology and Smoke. These paintings investigate abstraction from a feminine perspective. Critic Stephen Zepke described her work as characterised by ‘fascinating ambiguity’. In the early 1990s, Fong moved from figurative depictions of the female body to more metaphorical representations. Her abstract compositions recall cellular structures or microbes viewed through a microscope. At this time she began to drill holes in the surface of her paintings—a reference to wounding and autopsy. In Fong’s allusive, sombre paintings the traces and stains of the human body appear as a kind of ‘forensic evidence’.

The show includes three artists who explore their Māori heritage in their work: Parekōwhai, Robinson, and Fraser.

Parekōwhai eschews explicit Māori imagery. But, while his work uses an international art language, it insistently addresses cultural difference. Atarangi, a sculpture built from oversized Cuisenaire rods, refers to a new method of teaching Māori language. Suggesting both a primitivist figure and a minimalist sculpture, it mashes the Māori and the modern. The Indefinite Article puts a Māori spin on McCahon, creating a monumental sculptural version of McCahon’s 1954 cubist-text painting I Am, where McCahon quoted the name of God. By adding the word ‘he’, making it ‘I am he’, Parekōwhai creates a bilingual pun. ‘He’ may be the male pronoun in English, but it’s the indefinite article in Māori. Parekōwhai doesn’t stop with local heroes. His sculpture Mimi reimagines Duchamp’s canonical readymade, Fountain, as a kitset model.

Robinson questions his authenticity. His Percentage paintings advertise the watering-down of his Māori blood over the generations—to a mere 3.125%. Māori art may have a noble, spiritual tradition, but he decides to convert a car shipping crate into a makeshift hut and covers it in crude advertising slogans. Inside, the empty crate, a plaque declares: ‘Sold Out’. He also shows an airplane sculpture, clad in a patchwork of blankets—black, white, and red (Nazi colours as much as Māori.) The work nods to German art (to Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer) as well as to New Zealand colonial history (blankets, an important early trade item, are believed to have contributed to Māori deaths, by harbouring disease.)

Robinson’s plane, an ambivalent emblem of exchange, is chosen as the show’s hero image—a nod to its principal sponsors, Air New Zealand and the Tourism Board. It features on the cover of the catalogue. Air New Zealand's Thomas Barscht, says, ‘We know from surveys our clients are different from many other travellers from Germany—they are more interested in art and culture. We want to ensure that this intellectual and inspirational part of New Zealand is understood in Germany. It can only be good for our business.’ (The show will later earn Robinson a residency in Aachen.)

Fraser is the only artist whose work references Māori imagery overtly. She makes decorative installations—often site-specific—using electrical wire, ribbons, and braid. The work often conflates Māori imagery with courtly historical European imagery. She is also the only artist included to have previously exhibited in Europe, having shown at the international exhibition, Prospect, in 1993—also at Frankfurter Kunstverein. She creates her installation, Te Puhi (The Princess) on site in Frankfurt.

In Art New Zealand, Jonathan Mané-Wheoki observes that Māori art and artists have only recently began to be incorporated into contemporary exhibitions. He writes, ‘While ethnicity was not a criteria for the selection of artists in Cultural Safety, it happens that of the seven contemporary New Zealand artists represented, four are of Māori descent and their iwi affiliations are specified in the exhibition catalogue.’ Mané-Wheoki wonders why the catalogue is so specific with regard to the ethnic origins of the artists of Māori descent. He argues that the biographies promote the idea of Māori art, suggesting this is still the unique selling point of New Zealand art.

Cultural Safety is originally presented alongside Second Nature, a Peter Peryer survey show, and tours with it. City Gallery Director Paula Savage says these shows, ‘present a cultural and intellectual view of New Zealand to a foreign audience who are more used to seeing this nation represented by its landscape, sporting heroes, and agricultural produce.’ However, Peter Peryer’s photograph of a dead steer on a rural roadside causes controversy, after the Meat Board becomes concerned it invites an association with mad cow disease. Off-brand.