ARTISTS Laurence Aberhart, Rhondda Bosworth, Margaret Dawson, Megan Jenkinson, Fiona Pardington, Peter Peryer, Patrick Reynolds, Marie Shannon, Christine Webster CURATOR Gregory Burke OTHER VENUES Waikato Museum of Art and History, Hamilton, 28 July–2 September 1990; Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, 13 October–2 December 1990; Auckland Art Gallery, 31 January–17 March 1991; Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 17 April–19 May 1991; Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch, 30 May–7 July 1991 PUBLICATION editor Geri Thomas, texts Jim and Mary Barr, Christina Barton, Miro Bilbrough, Gregory Burke, Lawrence McDonald, Priscilla Pitts, Shona Smith

Subtitled Beyond the Documentary in Recent New Zealand Photography, Imposing Narratives argues a turn away from ‘the documentary’ in New Zealand photography. It includes 100 photographs by nine artists: Laurence Aberhart, Rhondda Bosworth, Margaret Dawson, Megan Jenkinson, Fiona Pardington, Peter Peryer, Patrick Reynolds, Marie Shannon, and Christine Webster.

Staged in the summer 1989–90 slot, the timing is auspicious—1989 being the sesquicentennial of the invention of photography, 1990 that of the Treaty of Waitangi. The show is cast as part of a lineage of contemporary New Zealand photography survey shows, including PhotoForum and Manawatu Art Gallery’s The Active Eye in 1975 and the National Art Gallery's Views/Exposures in 1982.

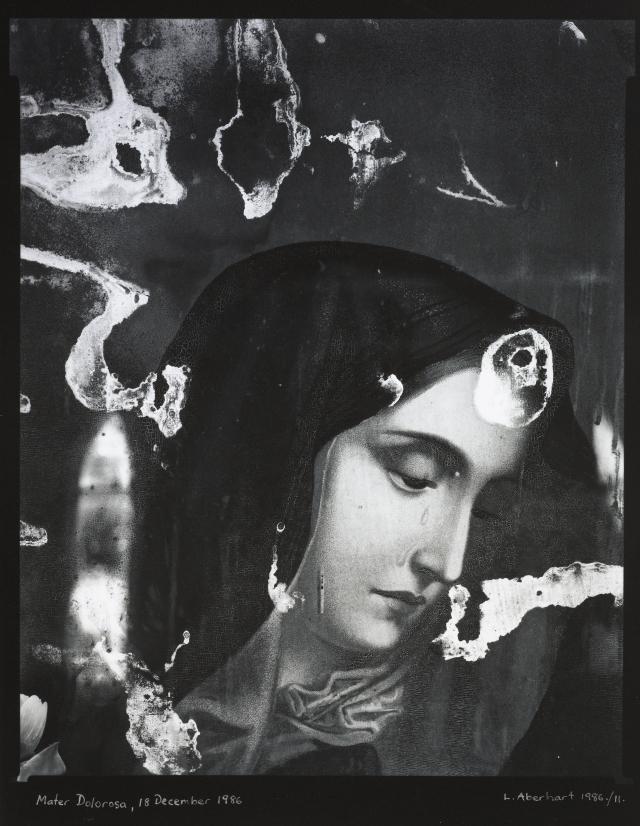

The artists’ approaches vary widely, as do the extents to which they move away from documentary conventions. Aberhart’s images of small-town New Zealand, its landscapes and memorials, retain a close relationship with the idea of the photograph as an objective record of reality. However, his anachronistic images recall early New Zealand photographers, acknowledging the historicising power of photography and nodding to colonial narratives. Peryer’s The Alexandra Clock (1988) is similarly a remake—his double-take on a found image, an old tourist postcard. Déjà vu!

The Imposing Narratives artists are linked by an awareness that images not only reflect but also shape cultural values. In the catalogue, curator Gregory Burke writes, ‘During the 1980s, in the age of the revitalisation of the marketplace, multi-nationalism, information processing, digital imaging, global television and sky networks, artists have shifted attention from the object to representation itself.’

Women artists are at the forefront of this shift. Six of the artists in the show are women. Several appear as subjects in their own photographs. Simulation and staging are popular strategies. Webster’s large glossy cibachromes feature a cast of shadowy figures absorbed in fetishistic role play and masquerade. In Moon Envy (1987), a naked man leaps in the air, with his hands fastened around a broomstick handle, ridiculing Freud’s penis-envy theory.

Riffing on the representations of women in mainstream media, Dawson revels in female stereotypes: frumpy housewife, Māori maiden, smiling Cherry Blossom Queen. In Women outside the House with Flowers (1987), she wears a man’s jacket and tie, with arms defiantly or self-protectively crossed. But beneath the jacket is a feminine floral skirt. Rhondda Bosworth’s fragmentary photographs of personal family snapshots also suggest split identities.

With the introduction of photography departments into art schools in the 1970s, photography was drawn into the art world. Jenkinson, Pardington, and Shannon are all graduates of the Photography Department at Auckland's Elam School of Fine Arts. Jenkinson and Pardington both prefer their photography ‘bent’. Jenkinson’s colour photomontages create a conspicuously artificial, fictional, allegorical world. Pardington’s photographs are also scrupulously art directed, and she favours heavily decorated, bespoke frames. Reversing the gaze, Pardington often places men centre stage. In Sebastian (1987), her subject’s beautiful bare buttocks are adorned with tiny cut-out paper cupids.

Shannon also photographs constructed scenarios. In her self-portrait, The Rat in the Lounge (1985), she sits on a chair, with her face concealed behind a cardboard rat-head mask. A cardboard tail pokes out below her skirt, and curls down to the floor, next to her black high heels. This photograph is autobiographical, re-enacting her waiting to leave for a costume party.

Many forms of ‘framing’ are key to Imposing Narratives. The catalogue includes six short thematic essays by writers, which are also presented as wall panels within the show. Jim and Mary Barr's text, ‘The Frame’, explains: ‘To inspect the frame we must move from the centre, first crossing the photograph’s grained landscape, to the image edge where exclusions are advertised and inclusions confirmed. It is at this point we can safely say that everything is either in or out of the picture.’

Critics take issue with the show. In NBR Weekend Review, Lita Barrie calls Imposing Narratives ‘a curator’s trademark show’, lamenting its pretentious reliance on overseas theory. ‘What is meant by narrative in the context of still photography remains unclear. Presumably, the title is a rather confusing restatement of the old cliché, “every picture tells a story”’, she complains. In the Evening Post, Ian Wedde observes that Burke’s ‘nifty curatorist title’ locates the show within his own curatorial genealogy, which also includes such shows as Drawing Analogies and Shifting Ground.

Wedde, however, concedes, ‘What is being documented here is, in fact, a moment of refusal led significantly by women. They have too often been on the receiving end of the camera’s roving eye, entrapped in ways predicated to the male gaze (or leer), caught unawares by the camera’s ability to take, shoot, capture or frame. They here declare their refusal to trust the documentary “moment of truth” canonised by Cartier-Bresson.’