For me every time I make a painting I’m dragging the whole history of painting with me. I identify with Quentin Tarantino. His films refer to films, to the whole back catalogue of cinema. A black limo appears and it’s more than just a gangster mobile, it’s every gangster mobile that’s ever been in any film. You have the whole history of the genre there immediately. Tarantino sees clichés as a rich shorthand. It’s like the brushstroke in my work, or the drip, or the splash. They’ve already been played out endlessly. But while they could seem thin, I want to redeem their richness. I want to pick up those things and use them invested with everything they have ever stood for.

—Judy Millar, 2005

Harold Rosenberg famously coined the term ‘action painting’ to distinguish the work of heroic abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock. In his 1952 essay ‘The American Action Painters’, he explained: ‘At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act … what was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.’ Rosenberg’s idea would have a huge influence, especially on artists who would carry the idea into the realm of performance. These days, however, we are critical of the idea of painterly gestures as direct expressions of feeling. We tend to see them as signs of ‘expression’—as pictures.

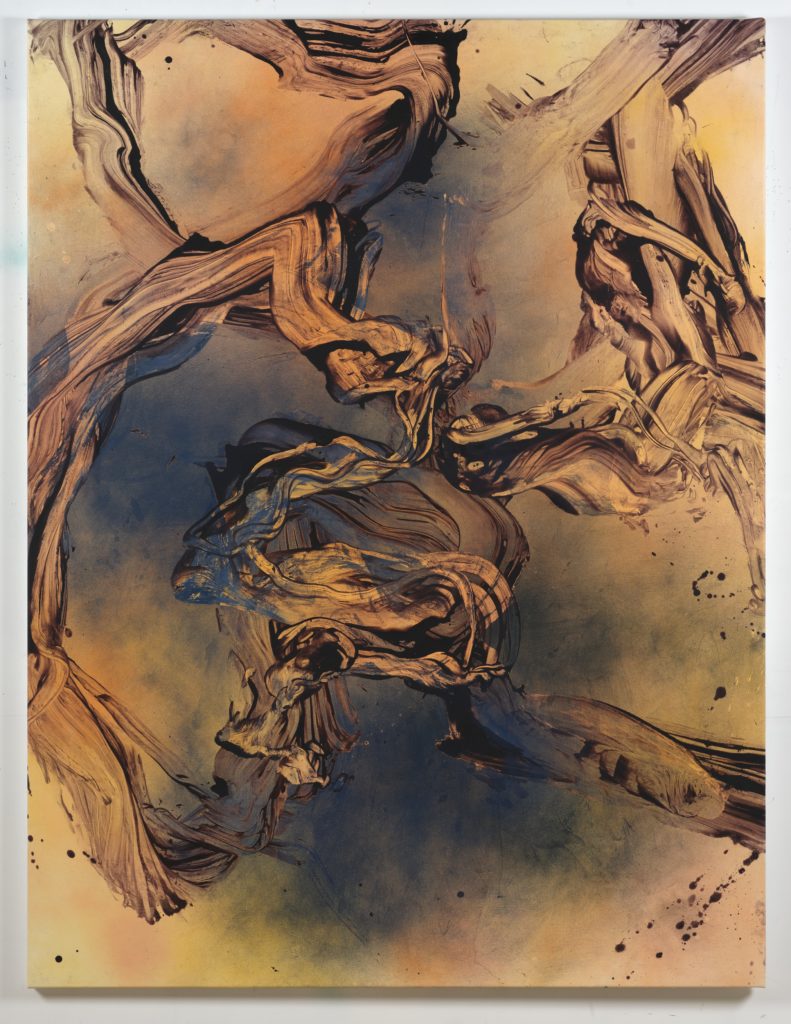

Auckland painter Judy Millar, however, wants to keep the baby and the bath water. Her paintings seem at once intensely physical and vital and highly mediated and mannered. Millar famously ‘paints backwards’, wiping paint off her canvases to create exaggerated, hyperactive brushstrokes that seem to float in illusionistic space. Full of drama, her works breathe life into the discredited idea of action painting—she’s a reanimator. Action Movie showcases two new series of paintings—three mural-size paintings in hot reds and pinks and seven portrait-format paintings in colder hues. The ‘hot’ ones started with the idea of making a sequence of painterly gestures as a framed ‘comic strip’. The ‘cool’ ones are hung in a line suggesting frames in a length of movie film.

Action Movie presents Millar’s paintings in conversation with two ‘direct’ films inspired by abstract expressionism, both made by painting directly onto film stock. Len Lye’s ‘rhapsodic’ All Souls Carnival—a collaboration with composer Henry Brant—was made using felt-tip pens and lacquer. In 1957, the film was projected on a screen behind musicians performing a Brant composition at New York’s Carnegie Recital Hall. Inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy, The Dante Quartet (1987) took American experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage six years to produce by painting images directly onto IMAX and Cinemascope 70mm and 35mm film stocks. In both films, the idea of painterly expressivity is complicated by being scrambled with the mechanics of cinema. Brakhage foregrounds this by slowing down and speeding up his footage, and by freezing frames.

Action Movie also includes films of artists in the wake of Pollock performing painting actions. From 1956 to 1966, Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, a key figure in the Gutai group, paints with his feet, while hanging onto a rope. In 1960, French artist Yves Klein employs women’s bodies as paint brushes in Paris. In 1962, Italian artist Lucio Fontana punctures a canvas for Belgian TV. All three engage with materials only in order to transcend them. However, American performance artist Paul McCarthy’s approach is more abject: he paints a line along the floor using his face in 1972.

Millar’s paintings are placed in conversation with these films to prompt viewers to consider the way her work toggles between painting and performance, presence and absence, material and ideal, the spontaneous and the considered.