CURATOR Justin Paton ORGANISER Dunedin Public Art Gallery OTHER VENUES Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 20 January–1 April 2001; Auckland Art Gallery, 10 November 2001–27 January 2002 PUBLICATION publisher Dunedin Public Art Gallery; essays Justin Paton, Emily Perkins

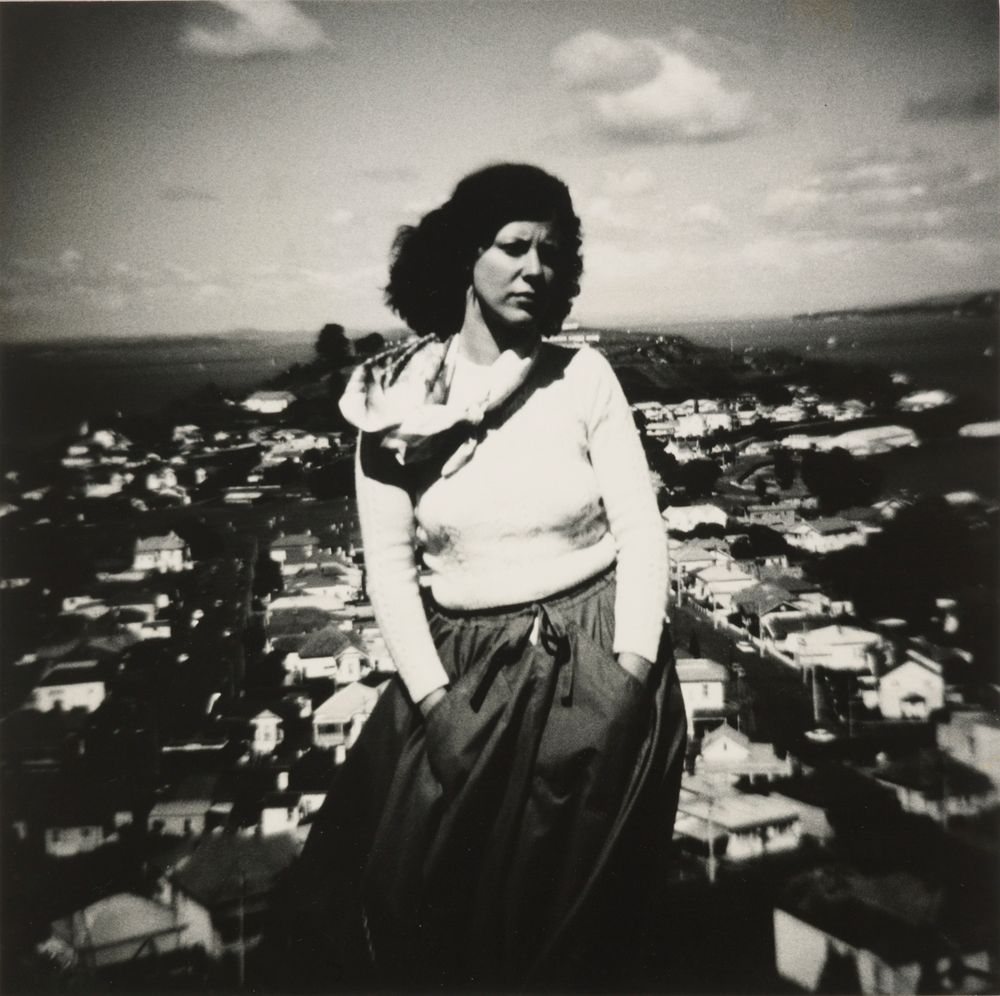

Peter Peryer is a major figure in New Zealand photography. Made in the late 1970s and early 1980s, at the beginning of his career, his broody portraits of his wife Erika Parkinson are among his most celebrated works and epitomise the subjective-expressive photography of the day. Erika: A Portrait by Peter Peryer gathers these images for the first time.

There is a tradition of photographers photographing their wives. Curator Justin Paton notes, ‘The images belong in an international tradition that reaches from Alfred Stieglitz’s cumulative portrait of Georgia O’Keefe (Stieglitz is a vivid ghost, quoted directly in several of these images) to Nicholas Nixon’s supremely tender portraits of Bebe Nixon.’ He could have also mentioned other prominent American photographers, Harry Callaghan (with Eleanor) and Emmet Gowin (with Edith).

Peryer compared his Erikas to film stills ‘torn from some larger story’, but later dismissed them as ‘the moody blues’. On the one hand, they typify the male gaze—the photographer constructing images of his muse for his own purposes. On the other hand, in the wake of Cindy Sherman, and especially gathered together here, they can be seen as feminist masquerade, with Parkinson as empowered agent and collaborator.

Alexa Johnson argues, ‘Peryer’s portraits have been described as all being portraits of himself and his own state of mind, regardless of the subject of the photograph. Yet the reality is more complex … Erika Peryer changes with time, and Peter Peryer’s photographs record the changes. There is a complex relationship between his intuitive planning of photographs and the effect of her personality on his vision.’ Parkinson selected costumes and roles for the images, from flapper panache to bohemian dishabille. Paton notes, ‘These photos evoke the fleeting pleasures of dressing up, but they also get at something larger—namely, the summoning power of photography, the strange, nearly alchemical ways in which the medium remakes everyday life … Erika’s and Peter’s role-plays and fictions become more “real” than real life.’

Parkinson calls the photos ‘portraits of strength’. She says, ‘As I recall it, I would have had an outfit and Peter might have said I'd like to take a picture of you in that. I absolutely loved it, I love dressing up and changing my looks and cutting my hair. When our daughter first saw the catalogue, she flicked through it and said: "Woman in search of a hairstyle."'

In the Listener, David Eggleton notes, ‘Erika is as much as the observer as the observed. You sense the model and artist interrogating one another: she is friend, stranger, muse, colleague, antagonist, lover.’ This echoes Emily Perkins’s sentiments on the ‘returned gaze’ in her catalogue essay: ‘Other people have written that you can chart the progression of Erika’s personal growth through the series, and that her confidence develops as feminist ideas take hold. But this series defies simple feminist interpretation.’ She quotes Parkinson: ‘I always doubted that stuff about the male gaze, I was quite happy to have anyone gazing at me.’

While planning the show, the Peryers separate, amicably. Peryer says, ‘The show is a homage to the times we were together, totally so. Erika has gladly spoken at the shows, she's given the floor talks, not me. I choose to see it as a celebration of the relationship, and not even in the past tense.’ An interview with the couple is published in the Herald.

At City Gallery, Erika: A Portrait by Peter Peryer is presented as part of a suite of exhibitions, Four Faces of New Zealand Art: Rita Angus, Michael Illingworth, Gavin Hipkins, Peter Peryer.

Peter Peryer dies in 2018, survived by Erika.