CURATOR Jonathan Turner PARTNERS Rosyln Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, with Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras OTHER VENUES Rosyln Oxley9 Gallery, 8 February–4 March 1995; Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 11 March–13 April 1995; Auckland City Art Gallery, 1 July–3 September 1995 PUBLICATION essay Jonathan Turner

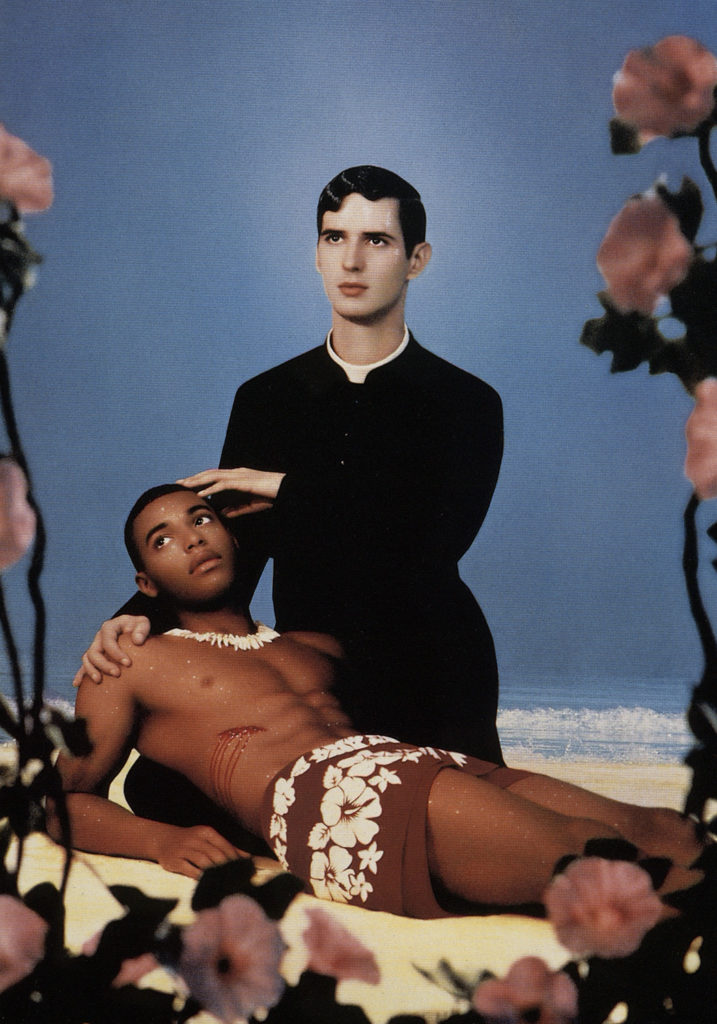

Pierre et Gilles (Pierre Commoy and Gilles Blanchard) are gay icons, famous for their hand-coloured photos of saints and sinners, stars and hunks. Pierre is the photographer, Gilles the painter.

The French couple began working together in 1976, after meeting at the opening of a Kenzo boutique in Paris. They left the party together on a scooter and haven’t been apart since. In the late 1970s, they came to public attention with their portraits of celebrities—including Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger, and Iggy Pop—for Façade magazine; but it wasn’t until 1983 that they had their first solo show.

Pierre et Gilles’s heady cocktail of celebrity, camp, and Catholicism comes to define fashion iconography of the 1980s. ‘There is guilt and there is gilt’, explains curator Jonathan Turner. They photograph everyone: Boy George, Marc Almond, Kylie, Jean Paul Gaultier, Catherine Deneuve, and male supermodel Enzo Junior—one of their favourite subjects. They create magazine covers, music videos, and an Absolut Vodka ad.

Pierre et Gilles’s style predates Photoshop. ‘An image takes a long time to do’, Pierre explains. ‘First, we reflect on the theme and put an idea in place, then complete a rough sketch, choose the model, choose the scene and build the set.’

The show features twenty-two of their original hand-coloured photos and is their first to tour the Southern hemisphere. It arrives in Wellington after its debut in the official programme for the 1995 Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras.

Beneath the glossy surfaces, the work has political cut through. Le Triangle Rose (a study of a gay concentration-camp prisoner) and their portrait of St Louis de Gonzague (the patron saint of those living with AIDS) belie the force behind their aesthetic flippancy.

Director Paul Savage says, ‘Pierre et Gilles photographs give new meaning to the words decorative art, with their high-camp send-up homage to the cheap images of the twentieth-century popular culture. They are sure to delight and intrigue.’ And they do. In a month, 43,000 people flock to see works from the Saints series alongside new photos, like Sur la Plage Abandonee (Rupert Everett drowned, in glittery chains) and Le Jeune Marquis (Salvatore Caputo as a young whip-bearing de Sade).

One photo—Glory Hole—is exhibited in a viewing booth with a warning sign. It portrays an ardent figure, dressed in leather, and holding an erect penis with ejaculate on his face. He looks up to the heavens. Savage tells media, ‘It has been separated out, leaving visitors to make a choice.’ The Gallery faces flak, not for showing the work but for its coy censorship. Visitors-book comments become the subject of media attention. One says, ‘Isn't it a little creepy to put a picture in a solitary booth? It screams of Ulysses in 1968.'

In the Listener, Philip Matthews says, 'Catholic in style, tongue-in-cheek in tone, the photos are painted to exaggerate the artifice and soften the features: skin here has the smooth seamlessness of a mannequin, faces have a deathly calm and all bodies are perfect. Immaculate conceptions, indeed.’ However, Evening Post critic James Mack, himself gay, writes, 'I found myself reacting strongly against this show. I stopped and asked myself it I was losing my sense of humour or titillation for the erotic/exotic. A giggle is OK but gays need to be portrayed in the world, not just as flittering glitterati dressed or undressed and inhabiting an unreal papier-mache film-studio world.’ He concludes, ‘I for one don’t want the world to think this is the only way I live.’

The accompanying catalogue is restricted to those sixteen years and over.