ARTISTS Michael Stevenson, Ronnie van Hout ORGANISER Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney OTHER VENUES Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, Adelaide, June 1997; Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 11 July–17 August 1997; Darren Knight Gallery, 27 September–25 October 1997; Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 31 January–19 April 1998; McDougall Art Annex, Christchurch, 27 April–31 May 1998; Auckland Art Gallery, 27 February–16 May 1999 PUBLICATION essays Rex Butler, Giovanni Intra

It's the end of the world as we know it. Ronnie van Hout and Michael Stevenson prey on the anxieties of a paranoid, future-obsessed society hurtling towards Y2K—the new millennium. Their show, PreMillennial: Signs of the Coming Storm, offers humorous insight into a brave new world where aliens and sinister government forces lurk behind everything. But is the show serious or a hoax?

Van Hout and Stevenson cast the art world itself as a kind of conspiracy. Their exhibition proposal explains: 'Through a series of systematic delusions the federal government, surveillance networks, military and alien technology, the 2000 Olympics and occultish influences, will conspire in a heinous plan of New World Order Proportions. Art's and artists' complicit role in all these events will not be underestimated. This exhibition will expose the truth behind our date with the next century.'

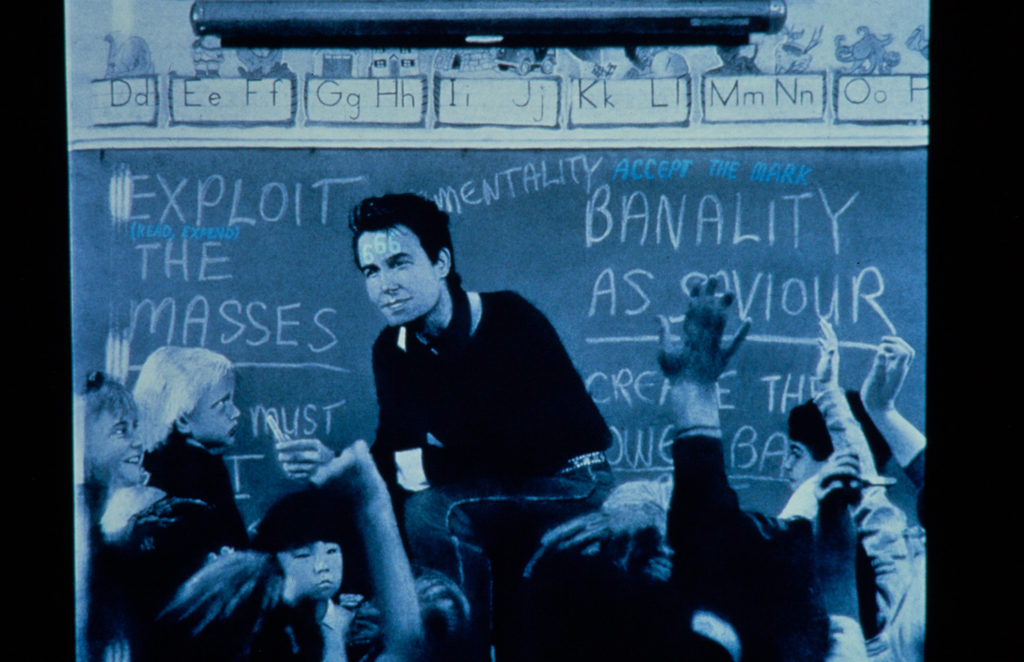

Stevenson’s drawings reproduce art images from magazines. When lit by ultraviolet light, they reveal concealed messages. An image of Jeff Koons in front of a classroom of kids, from Artforum, reveals the mark of the beast, ‘666’, writ across his forehead. A Cindy Sherman photo, from Time, bears an ominous iteration to obey. An aerial view of From Scratch, from Art New Zealand, is overlaid with Illuminati imagery. Curator Robert Leonard writes, 'Rewiring his source images with paranoid links, masquerading as “what really happened”, Stevenson links contemporary art to other forms of extremism, exposing the heart of darkness behind art’s humanistic press release.'

Ronnie van Hout's installation finds parallels between a series of ghostly UFO photos and his (un)employment documentation from the New Zealand Labour Department. As an unemployed artist, Van Hout suggests his own status in the system is akin to a UFO sighting. On his Labour Department forms, he’s listed as 'an artist seeking work', highlighting the common perception that art is not a real job. And, maybe it isn't? Van Hout's misuse of these official documents taps into our distrust and fear of authority. Van Hout also exhibits twelve small model dioramas with the common theme of destruction: a ruined house, a dead solider, a grimacing gorilla, a checkpoint, oil drums, a well. The immaculately finished scenes conjure up an image of the artist as a lonely hobbyist working in a garage, an outsider, maybe even a little unhinged.

The catalogue is dedicated to 'all those who seek the truth’. In it, Australian art historian Rex Butler compares van Hout and Stevenson to Mulder and Scully from The X-Files. Stevenson is Mulder, the 'true believer’, and van Hout Scully, 'the sceptic’. Butler then asks us to consider Mulder and Scully as a pair of squabbling art critics. 'Think of Kant's Critique of Aesthetic Judgement as The X-Files of the eighteenth century.’ Giovanni Intra's essay ‘For Paranoid Critics’ begins with Intra imagining the word conceptualism as a piece of chewing gum spat out on the pavement. It is post-modernism, now viewed in hindsight.