ARTISTS Terence Handscomb, Julia Morison, Ralph Paine, Merylyn Tweedie, Christine Webster CURATOR Wystan Curnow ORGANISERS Artspace, Auckland; Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth OTHER VENUES Artspace, 6 October–6 November 1987; Govett-Brewster Art Gallery; Manawatu Art Gallery, Palmerston North, 4 August–2 October 1988; Hawkes Bay Art Gallery and Museum, Napier, 4 November–4 December 1988; Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 3 August–10 September 1989; Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch, 20 September–19 November 1989; Sarjeant Gallery, Whanganui, 5 December 1989–4 February 1990

Sex and Sign is a sign of the times. It introduces a new group of New Zealand artists inspired by poststructuralist theory, particularly Lacanian psychoanalysis. Anyone expecting pornography is disappointed. Instead, the show overflows with words, diagrams, algebra. Curator Wystan Curnow says, 'The problem is gender; its cultural as opposed to its biological construction, and the oppressions which flow from it.'

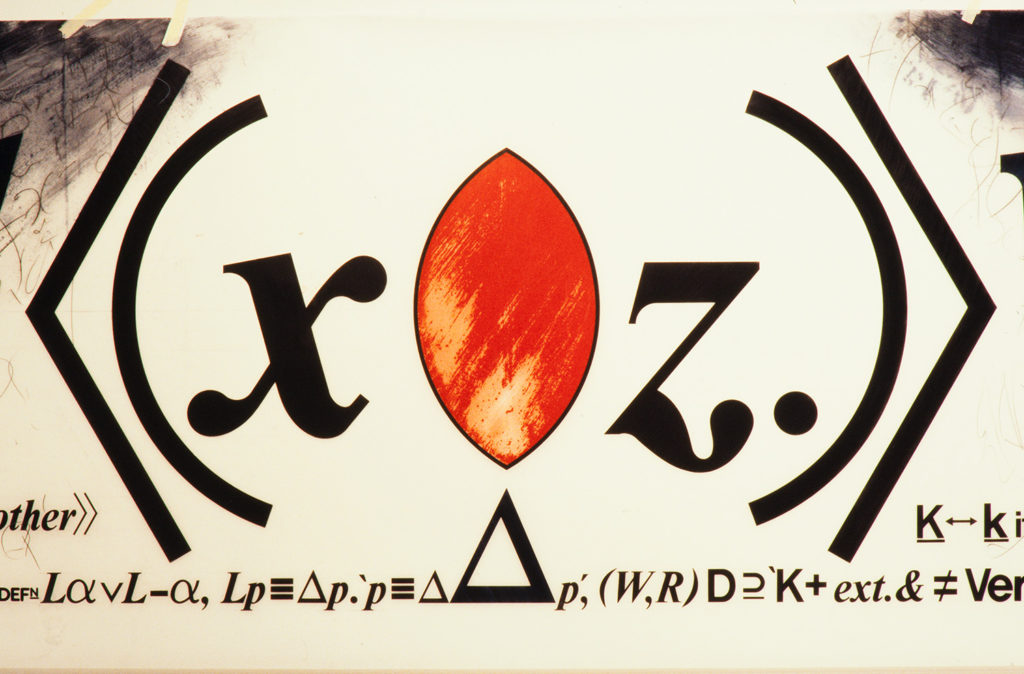

Terence Handscomb's Recursive Phallus (1987) is an eight-metre-long drawing on polyster drafting film featuring obscure Lacanian equations. A central 'rosebud' form represents both a menstruating vagina and an anus. The artist is citing Freud's idea that, as 'a bleeding wound', the vagina represents a castration threat. In the Dominion, Rob Taylor writes, 'Whatever specialisation is required to discern whether Lacan passes Handscomb's test, more generally it can at least be surmised that the red rugby ball at the shape at the very centre is, for Handscomb, an orifice of anxious ambivalence in his consideration of Lacan's rewriting of Freud's Oedipus complex.'

Ralph Paine's diagrammatic paintings cite diverse references, including Leda and the Swan, the Tree of Life, and the Children of Tane. Curnow describes his work as 'a grab-bag of signs whose organisation, signified by various internal framing devices, resembles the syntax of a sentence'.

Merylyn Tweedie's Entering Commercial Distribution (1987) consists of typed pages—with many words erased with correction fluid—glued to larger drops of paper. The text's baffling, fragmented nature resists any close reading.

Recalling advertising images, Christine Webster's large glossy cibachromes are the raciest works in the show. Moon Envy (1987) inverts Freud's notion of penis envy: a male nude hovers in darkness, miraculously supported by a witchy broom. In Self Defence (1987), a woman waves a red flag before a phallic horned beast. Critic Lita Barrie says Webster's images have a fetishistic decadence that recalls 1930s Berlin. It's not a compliment.

Julia Morison's works are based on occult sources: kabbalism, hermeticism, alchemy. They are intended as a critique of patriarchal Christian values, and emphasise 'hermaphroditism'—scrambling rather than ring-fencing male and female. Somniloquist (1987)—the title means 'sleep talker'—combines ten logo forms based on kabbalism's sefiroth, a signature element in Morison's work. Representations of scissors and surgical instruments are also transferred onto the wall—to convey the idea of the artist as explorer and examiner—and framed phrenology diagrams hung upon it. In the Dominion, Rob Taylor says, 'But the spectacle which finally makes this exhibition essential viewing is Somniloquist ... Morison ranges through the arcana of the alchemists, Greek mythology, the Jewish cabala, and the ancient Egyptian teachings of Hermes, in quest of instruments for exploring and examining the intricacy of human belief and behaviour.'

Sex and Sign presents its artists as bookish, as readers 'undaunted by the most difficult texts'. In the catalogue, the artists quote tough texts they've been reading: Jacques Lacan, Ferdinand de Saussure, Julia Kristeva, Kate Linker, Felix Guattari, John Money, etc.

Sex and Sign is slammed by local reviewers. In the Evening Post, Ian Wedde writes, 'Wystan Curnow has never been comfortable with the visual or aesthetic aspects of art, preferring to engage himself at the conceptual edge.' The show closes three weeks early. In National Business Review, Lita Barrie concludes, 'Its premature demise at Wellington was an indictment of that gallery's disorganised exhibition programme and it was oddly symbolic that it did not last the distance.' She dismisses the show as 'a transparent sham of intellectualism' that 'merely reflected the curator's ego'.