CURATORS Mary Kisler, Justin Paton ORGANISERS Auckland Art Gallery, Dunedin Public Art Gallery OTHER VENUES Dunedin Public Art Gallery, [dates]; Auckland Art Gallery, 5 July–14 September 2003 PUBLICATION essays Mary Kissler, Justin Paton

This is the first substantial New Zealand show of British painter Stanley Spencer (1891–1959). Comical, humane, and visionary, his work is driven by his religious convictions and turbulent personal life.

He spends most of his life in his home town, the village of Cookham. As a child, he believed biblical events took place there, witnessed by the locals. ‘When I was young about the village as a child, I was aware of a wonderful something which was everywhere to be felt, it was bang all around me, it was heaven as clear as the Cookham day’, he says. In his work, contemporary Cookham plays host to biblical events. His Resurrection (1926) is set in the local churchyard, with the River Thames standing in for the River Styx and holidaymakers on it for spirits departing to the underworld.

Spencer is not universally praised. Some see him as the ‘divine fool of British art’, others consider him the greatest figurative and religious painter in twentieth-century British art. He is knighted in 1958, the same year as his cancer diagnosis, and dies a year later. A critic writes, ‘it is fair to say that Spencer’s work was divided into two distinct categories—comical versions of events and intense realism.’ He becomes a member of the Royal Academy in 1950.

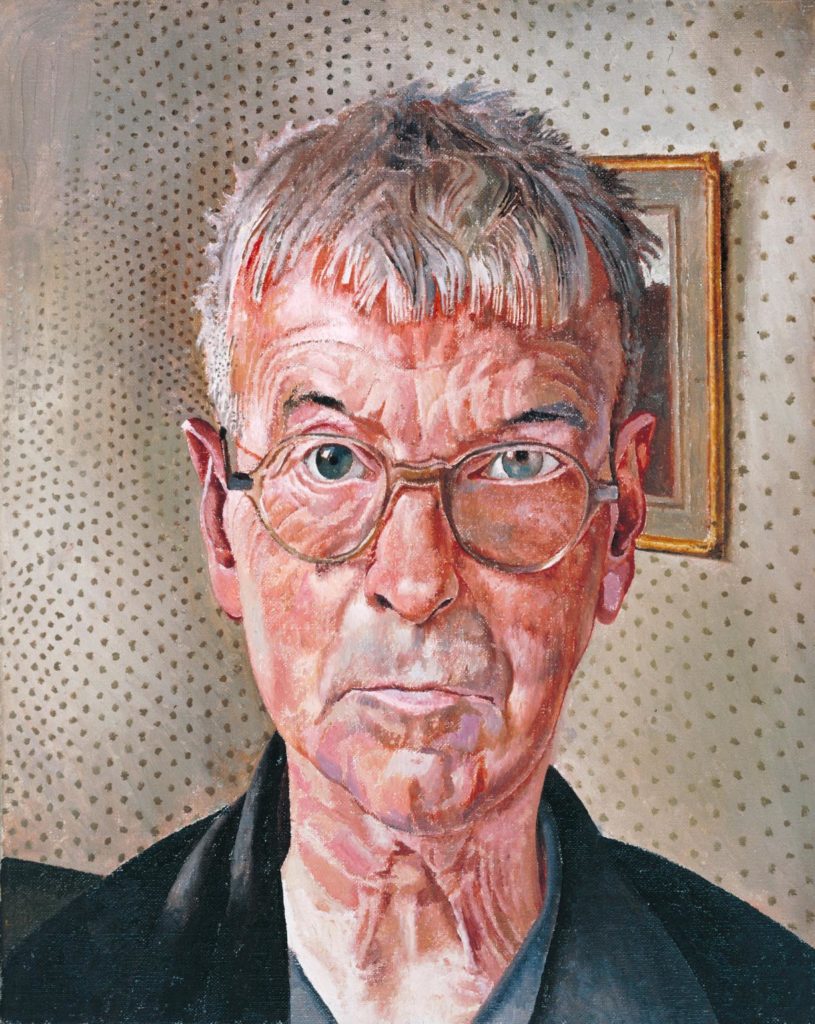

Located at the entrance of the show, Self Portrait (1959) is his last self portrait. The extreme close up conveys physical and psychological intensity. Many of the thirty-two works in the show are sourced from Australasian collections, with some coming from English public collections, including the Tate. The show includes four of the eight completed canvases—and one unfinished canvas—from Spencer's series on Christ in the wilderness, painted in London in 1938.

On the night of his death, Spencer believes he is visited by angels. He takes up a pen and writes, ‘I am never weary, never bored. Why should you think I am? Sadness and sorrow is not me.’