PUBLICATION essay Heather Galbraith

Practical Metaphysics seems like an oxymoron. The show picks up where Tony Lane’s 1989 City Gallery solo show left off. The former Wellington-based painter riffs on art history, from thirteenth-century Italian painters such as Giotto to seventeenth-century Spanish still-life painters, from high art to folk art, from altarpieces to vernacular shrines. Rendered in fresco on panel, in gilded frames, his works recall icons. Featuring religious motifs (wounds, tears, hearts, stigmata) and everyday objects (a table with wine bottles, a chair, a linen cloth, a necklace, a coil of rope), they hint at a range of cultural and personal meanings. In the Dominion Post, Mark Amery writes: ‘without the slightest tinge of irony or debasement, [Lane] plays with the theatrical staging of the devotion, as if letting us in on the secrets behind the magic whilst still setting off fireworks for the mind’.

The title of the exhibition, Practical Metaphysics, seems like an oxymoron; our contemporary understanding of ‘metaphysics’ as ‘immaterial’ is dismissed. This rather embraces a more ancient definition—namely that metaphysics seeks to understand the nature of all reality, be it visible or invisible, material or immaterial. Tony Lane’s paintings merge the symbolic and experiential, creating uncanny realms that bend meaning and association. This survey gives a comprehensive view of his work, featuring his richly crafted paintings and a selection of ceramics. It picks up where Lane’s previous solo project at City Gallery left off in 1989, reaching to the present day.

Lane depicts objects that are part of our daily lives; a table with wine bottles, a chair, a linen cloth, a necklace, a coil of rope; common forms which suggest a myriad of cultural, religious and personal meanings. His enigmatic visual language is deeply connected to painting’s history, from thirteenth century Italian painters such as Giotto to the Spanish still-life painters of the seventeenth century. His interests extend outside of high-art to folk and outsider art, collapsing their hierarchy by revealing intriguing crossovers.

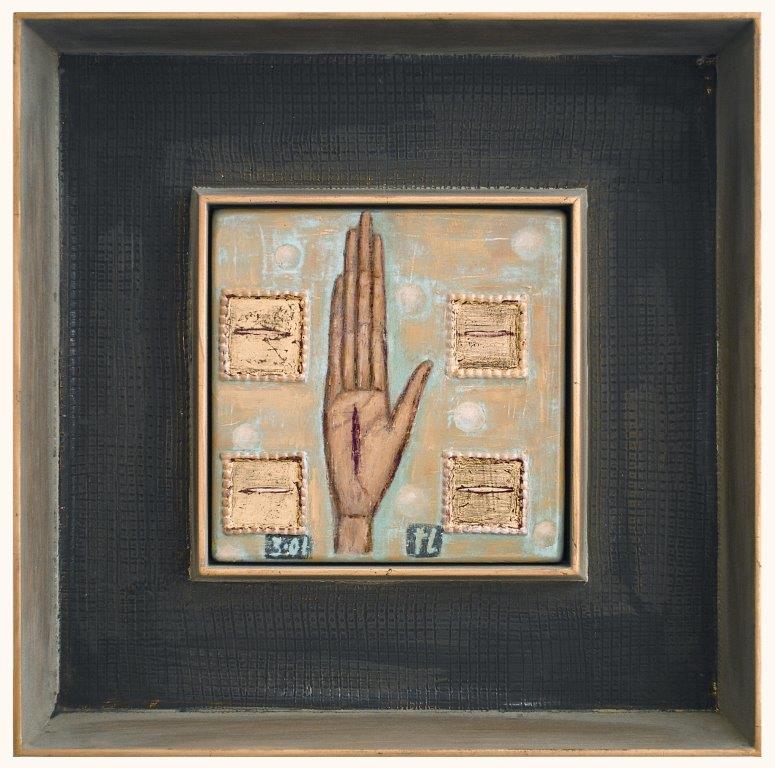

A series of trips to Britain, the USA and Europe in the late 1980's brought Lane face-to-face with historical and contemporary works that were only available in reproduction within New Zealand. It also revealed the countless social frameworks within which art could be embedded, playing a role in routine and ritual. Occupying anything from the museum to the street-side shrine, the multiplicity of meanings that could arise captured Lane’s imagination. The 1989 exhibition at City Gallery showcased his initial responses to these trips. His practice revolved around producing unconventional frescoes, where figurative forms were dispersed across panels rather than applied straight to a wall or ceiling. The works included in this exhibition are instead akin to religious icons, encased in gilded frames and utilizing bronze, silver and gold leaf. Wound (2001), contains a hand with stigmata removed from the religious manifestations that have come to define it, yet its symbolism still imparts a mysterious spirituality. He often reduces the religious subject to a single symbol—wounds, tears, hearts, stigmata—repurposing its essence to conjure more abstract implications.

Much of his work involves the careful processes of creating still-life, Lane delicately selecting the objects he places within his compositions. Two Hanks (1990), Table Wounds (1996) and Table with Wine Bottles (2001) can be considered in this vein, but throughout Lane introduces a surrealism that destabilizes any hope of confident analysis. As Mark Amery writes in a review for The Dominion Post: ‘without the slightest tinge of irony or debasement, [Lane] plays with the theatrical staging of the devotion, as if letting us in on the secrets behind the magic whilst still setting off fireworks for the mind’.

While Lane borrows fragments of images or formal pictorial devices from art history he does so selectively and knowingly; he is not a copyist, rather he re-constitutes aspects of visual language with the awareness that our understanding of the past is always partial and subjective. This engagement with historical visual culture is combined with his desire to radically reinstate the capacity of images to convey meaning in a contemporary context.