PUBLICATION essays Judy Annear, Rex Butler, Chris Chapman, Lynne Cooke, Blair French, Elizabeth Knox, Gerald Matt, Tracey Moffatt, Cushla Parekōwhai, Jane Rankin-Reid, Paula Savage, Lara Strongman, Morgan Thomas

Making art is quite therapeutic, like chopping vegetables, it calms me down and keeps me off the streets. If I wasn’t making photographs or films I could be going around slashing car tyres with a butcher’s knife.

—Tracey Moffatt

Tracey Moffatt is arguably Australia’s most internationally successful contemporary artist. Her work is informed by her growing up as an Indigenous Australian in a working-class Brisbane suburb, with a taste for popular culture. The show includes four films and eight photo series, ranging in approach and aesthetic.

Set in a barren landscape, Moffatt's short film Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1989) depicts an old white woman being cared for by her adopted Aboriginal daughter. The girl’s loneliness, frustration, and loss is conveyed in unsettling silence. Also set in back blocks Australia, Moffatt's first feature-length film, Bedevil (1993) presents three supernatural tales as a means to redefine racial stereotypes. The stories were passed down to the artist when she was growing up. In contrast to these highly stylised, art-directed films, Heaven (1997) is a handicam record. Moffatt became the ultimate voyeur as she goaded male surfers publicly dressing and undressing on Sydney's Bondi Beach.

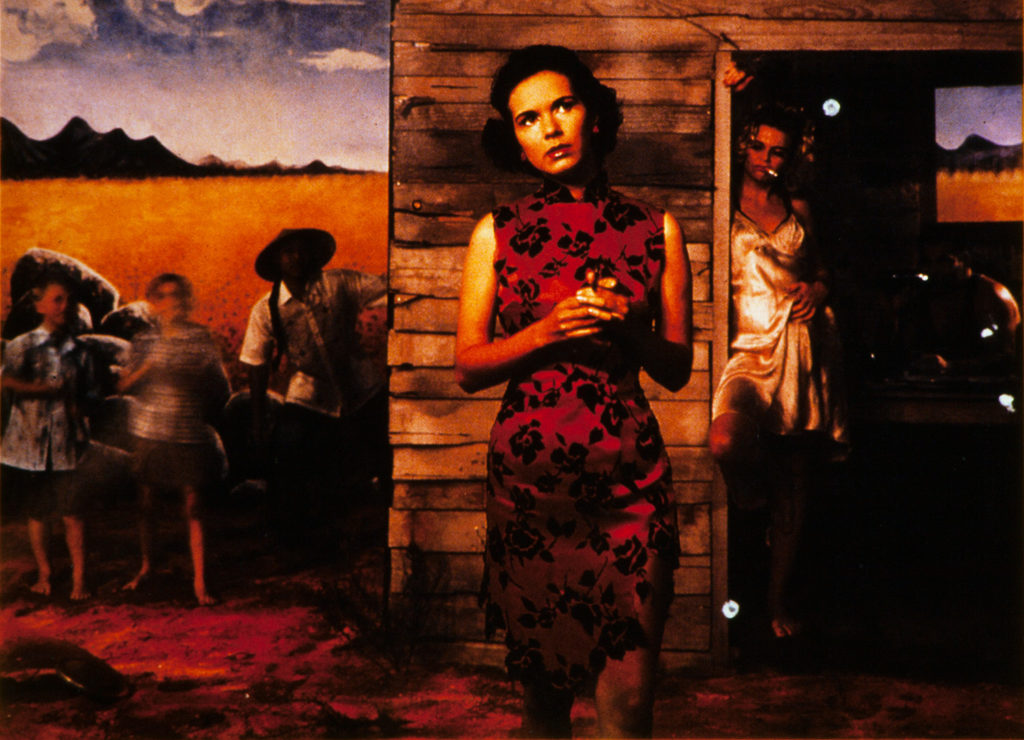

Moffatt’s photo series often have a cinematic logic and cinematic references. The storyboard-like Something More (1989) is her most iconic photo series. It is highly artificial, recalling movies shot on sound stages. It refers to the melodrama genre—overwrought takes of fallen females. It presents a rich fragmented narrative with suggestive images of violence, glamour, and disappointed dreams. In nine shots, it tells the tale of a beautiful young Aborigine girl—played by the artist—seeking escape from her rough, bleak rural existence. The first shot is optimistic, but the final shot finds her lying dead on road to Brisbane. In Pet Thang (1991), dreamy images of a nude woman and a sheep float in the dark. Scarred for Life I and II (1994 and 1999) are based on true stories of childhood trauma told to the artist, restaged in the format of faded Life magazine pages. GUAPA (Goodlooking) (1995) conjures up the frenetic world of roller-derby girls.

Up in the Sky (1998) is another storyboard narrative addressing Australia's ‘stolen generation’—the Indigenous children taken from their families and forcibly relocated under Government policy. It was shot on location in a remote town in outback Queensland, ‘a place of ruin’ populated by misfits. Laudanum (1998), a series of nineteen photogravures shot in a colonial mansion, conjures a hallucinatory gothic narrative of sexual violence between a white mistress and her Asian maid, filtered through what seems to be a drug-fuelled haze. In the nineteenth century, laudanum was a popular opiate drug used to calm colicky babies and ‘hysterical’ women. Invocations (2000) offers scenes of fantastical forests, swirling dessert wastelands, killer crows, and possessed bodies. In Fourth (2001), pictures sportspeople from the 2000 Sydney Olympics who ranked an anticlimactic fourth-place in their events.

The Moffatt show runs in conjunction with two other exhibitions with an Australian focus, Sydney Nolan: Ned Kelly Series and Mikala Dwyer: An Australian Artist’s Project. As a Dominion Post review explains: ‘Her work seems to pick away at some imaginary scab in Australian society, revealing a raw, weeping wound of troubled childhood, racial conflict and sexual perversion.’ It concludes, ‘Before they arrived, the Ned Kelly paintings were described as iconic, as a way for the viewer to delve into the Australian psyche. But after seeing the Tracey Moffatt survey … I felt much more enlightened about what it is to be an “Aussie."'