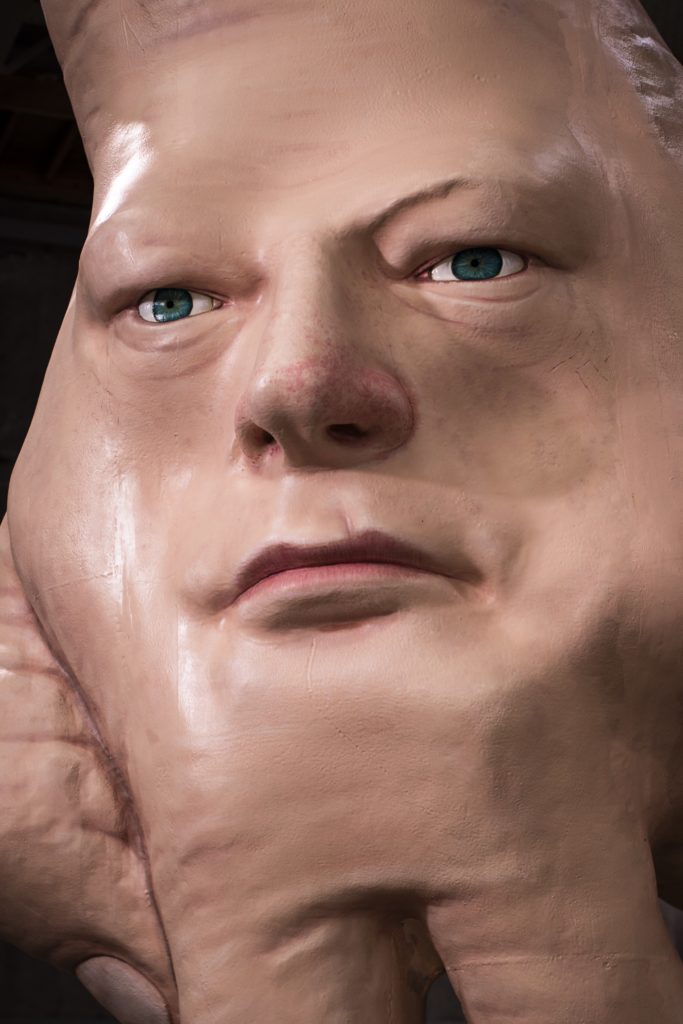

Megan Dunn talks to Ronnie Van Hout about Quasi.

‘Quasi is in the wrong place’, wrote art critic Warren Feeney, in the Christchurch Press, arguing it should be removed from the roof of Christchurch Art Gallery. Quasi is named after another roof-dweller, Quasimodo, the orphan and ‘monster’ from Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. Now Quasi has touched down on the roof of City Gallery Wellington, the last occupied building in a newly evacuated Civic Square. Quasi seems wedded to disaster. Is it in the right place?

Megan Dunn: In Hugo’s novel, Quasimodo is deaf from his constant bell ringing in Notre-Dame, so he uses sign language. Your Quasi is a giant hand bearing your face—what is it signing?

Ronnie van Hout: Quasi represents the history of the outsider, the freak, the artist. Like Quasimodo, he is not a real monster, but a misunderstood abject self who is denied a name, who bears only a description—as misshapen.

Quasimodo was abject, yet ultimately a hero. But in your art, the body never seems heroic, rather something shameful to be overcome.

Quasimodo said, ‘I’m not a man, I’m ugly, don’t look at me.’ Ugliness is a form of otherness. Today, we have to confront so many images of ourselves, to see ourselves as others do, which is all very problematic. We are both the persecuted freak and the outraged torch-wielding masses.

Should we love Quasi?

How much could we love a detached hand that has taken on a life of its own?

Do you have a favourite Quasimodo from film?

It’s hard to go past Charles Laughton going the full Eisenstein in the 1939 version.

Why did Quasi irk some people in Christchurch?

It’s not difficult to see why. Apart from the usual ‘taxpayer’s money’, ‘rip off’, ‘the artist is having us on’ brigade, it’s those with firm beliefs about what art is that get annoyed. Quasi got put on a top-ten-most-embarrassing-artworks-in-the-world list and art critic Warren Feeney wrote his article, ‘Ten Reasons to Scrap Quasi’.

People find Quasi lewd.

Some people (men mostly) made some suggestions about the hand’s pose that I found misogynist and offensive. It makes me sad that some still think that sort of thing is funny.

Quasi is based on your own face. You use your own likeness as a kind of mask. What do masks reveal and conceal?

In my work, I try to be different things. The masks change from moment to moment. At the moment, I’m in artist-being-interviewed mode. Actually, ‘the interview’ is one of my recurring themes. My new video, Learning How to Sculpt (2019), is based on YouTube how-to videos, where someone talks to an imagined audience. I play a version of myself, meandering from topic to topic, from confident to self conscious. I play a persona that’s a failure, but is so unaware that he just keeps plugging away.

You’ve become an unlikely go-to public sculptor. You’re good at the challenges public art presents. Do you approach public artworks differently?

Public art bothers me, because it’s not really art. I see public art more as signs. New Zealanders make good signs—Colin McCahon was a great signwriter.Quasi makes a pretty good sign. He takes the heat and gets the Instagram hits. He never gets to go inside to hang with the real art. He’s like a working-class schmuck at a private-school event, who feels terribly out of place.

Comin’ Down (2013), another Van Hout doppelganger, had an impossibly long arm pointing skyward. Before Quasi, it also occupied a Christchurch rooftop looking out over a fallen city. It was more positively received than Quasi.

Comin’ Down was about gesture in its simplest form—pointing. When you point at something you’re asking someone to see something you’ve seen. You’re asking: ‘Can you see that?’ Pointing is a basic form of communication. Even though the pointing arm is absurdly stretched, it’s a fairly straightforward work, whereas Quasi is ‘weird’—but also about ‘weirdness’. I spent most of my childhood being called weird. A few years back, I realised people were still describing me that way despite how ‘normal’ I tried to act. Of course, adults kicking balls over painted lines between vertical poles is not odd.

What was your earliest public work? How has your approach changed?

My first public work was Shift for Scape in 2006. I installed a shed from my family home in front of Christchurch Art Gallery. Like all public art, it suffered from compromise. I wanted people to think about things being moved from one place to another, but mostly they thought about sheds as objects and other dumb stuff. I tried again, at Te Papa, by reproducing a family shed twice (A Loss, Again 2008). I wanted to create a dialogue about the collected memory of the museum and what is forgotten, but the work was interpreted as being about personal nostalgia, my childhood. It was discussed like I was some sort of everychild, seen through a saturated Kodachrome gaze. But even sentiment couldn’t save my sheds. Te Papa destroyed them, claiming they couldn’t afford to take them off the roof. My plea for the container of national treasure to take in my own little containers was rejected.

What’s your latest public work?

Public art takes a long time to come together. My Boy Walking recently went up in Auckland. It’s a realistic, five-metre-high sculpture of a walking boy. My intention was to make a positive, hopeful image, without my usual abandonment issues. The image—based on a photo in my 1995 series Mephitis featuring model figures—is about perpetually becoming. The past is memory, without trauma, and the future is an open door, which you walk through. You were outside, now you are inside.