.

For the latest instalment in our essay series ‘Art History Is a Mother’—developed in partnership with Verb Wellington—Talia Marshall discusses photographer Ans Westra’s 1967 book Maori.

I guess that technically my copy of Ans Westra’s Maori is stolen. I was on the run then from a life that wouldn’t stop imploding, and, while I shed people, places, and things, the substitutes were whipped into my human tornado. Sucked into a chaos that took me months to register, and in the aftermath’s grey, stinking wreckage, I was ungrateful to still be alive. But I loved my new book.

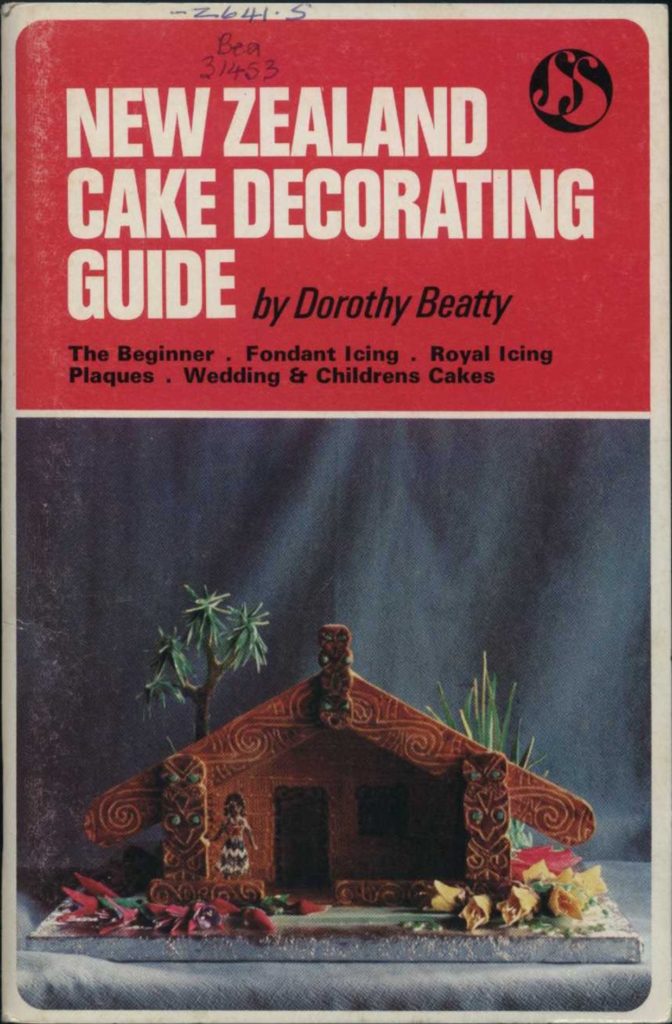

My possession of Maori was part of a larger argument between me and a man who had helped to raise me in the absence of my Māori whānau. He was only seventeen when I met him at two as Mum’s wary pāua, but he quickly won me over. They were at polytech studying early childhood and we ended up living together with Sue off the top of Cuba Street in a rickety cottage. I can remember him putting food colouring in my bath to make it go red, blue, and purple. When I turned five, he made me a gingerbread-house cake with chocolate fingers for the roof and immaculate green coconut grass out the front.

Maybe it’s ironic that we fell out as adults in Riwaka, a place I whakapapa to and he had offered as a refuge to me, his ‘favourite niece’. Maybe it’s ironic that, in the wall-to-wall kitsch of his cavernous whare, this Pākehā had so much Māori stuff—the kind you get from a secondhand shop or sieve through the ‘funky’ ‘kiwiana’ listings of TradeMe for, to call treasure rather than taonga.

The book was in the back of my silver Audi as I drove over touchy Takaka Hill and away from Riwaka in a hurt rage. The new car was my other decent consolation prize in the tornado, but the kurī was already destroying the black leather upholstery with his anxious terrier antics.

Three years later, I found myself almost homeless and living with the kurī in the furry miasma of the car, but instead of the Audi I now had a beat-up red Nissan I’d christened Bobby Jo. I drove her to Roman’s place in Gisborne with the oil light on and my mental-health companion-in-chief panting his ageing, rancid, Jack Russell breath over my shoulder. I was running out of options and this was a sound offer from Roman, my son’s father, to come and stay with him. On the way to the coast, Māori were everywhere I looked. Except for Tirau, which had a Trelise Cooper outlet store in lieu of tangata whenua, and I thought: why is Tirau? The glib answer is horses, dairy farming, and shit taste in clothes.

I saw Māori in Rotorua, Tokoroa, Whakatāne, and Ōpōtiki, and then in smaller, more mysterious places like Nukuhou, with its roadside marae and the kehua I felt at my nape driving through Tāneatua where a puppy trotted loose in the rain. I drank in the mythic promise of the road signs indicating the turn off to Galatea and Murupura before I cut through the brooding valleys of the Waioeka gorge. Roman had warned me about Waioeka, telling me I wouldn’t want to break down there after midnight. I felt my eye snapping shut like a shutter behind a lens on all the Māori I witnessed animating the cakey North Island whenua. And, in my madness, all these Māori everywhere were such a comfort to me. I did not need to open a book to find my own people, even though I still had Maori with me in Bobby Jo, my lucky, unlucky book.

In Gisborne, I kept trying to show Roman the images in Maori but he gave me Nāti side eye and said: no one cares about Ans Westra, Talia, write something positive. It was as dismissive as the comment I found searching her name on Twitter, which remembered Ans as that hippie lady who turned up on the coast scrounging for a feed. My worry was how much that label also fit me.

And then, a few weeks later, because he likes to toy with me, Roman mentioned some aunties on a rohe Facebook group who were sorting out who was who in one of Westra’s unnamed images. It had already occurred to me that this was one of the chief flaws of the book James Ritchie wrote the text for, this lack of names and identifying hapū and marae. And it was the lacuna I wanted to write about. I felt that Ans Westra had gapped it on us and that her career was built on a simplistic, homogenous view of Māori. A view that battled with my initial response to the photos, which was to feel seduced by their vibrating dream. I physically love some of Westra’s images. I feel a pull towards them, and this is a rare feeling for me when it comes to art.

And I was as anonymous as her photographs in Gisborne, lying on the couch in my freshly dead father’s black puffa jacket, which was the bulk of my inheritance. My bulk on the couch sunk one of the squabs lower than the others with the shape of my sorrow. I mean, I rarely moved. Sometimes I would heave myself outside to smoke on the porch and look at the panelbeaters over the road through the straggly winter hibiscus.

Eventually I did leave the house and bought cheap and cheerful leopard-print tights and garish muumuus from a trash emporium called Art! Fun! Wear! on Gladstone Road, so my lying down had a more tropical, festive feel after that. I was exhausted and wounded but I was safe in this dingy haven. I hadn’t felt safe for a long time.

Gisborne is so far from another main centre. The op shopping is excellent, with plenty of whenua-rich farmers and wealthy Pākehā in the greater area who have nowhere else to drop off their dead or unwanted loot. In the Salvation Army, this mixed with cheaper plastic plates ringed with kowhaiwhai patterns and the sign on the women’s clothes rack read ‘Wahine’. At the local auction house, there was a golliwog in the rafters, and I squinted up at it wondering if anyone from Ngāti Kāren, desperate to decolonise her thinking, had demanded that it be removed. I was not that bothered by the crass doll. It seemed like a toy for creepy old ladies rather than kids.

Yes, golliwogs are historically gross and racist, but it was easily remedied, compared to the fact there were almost no rentals available in Gisborne and homeless or precarious Māori were the least likely to be picked as tenants. On their own whenua.

I saw men walking or cycling the streets with everything they owned in a backpack, who slept under bridges or trees by the poisoned river. One day, a Pākehā man turned up at the front door with a raw steak in a plastic bag and asked if I would cook it for him, because he was living in his car. But Roman had said he didn’t want any homeless cunts turning up at his door, apart from me, and I was ashamed and relieved that his voice was in the back of my head when I said ‘no’.

Besides, if anyone dared to jump the corrugated-iron fence out the back, Roman’s pit bulls would have ripped them apart like lions, and I kept a watchful eye on my kuri, only letting him piss and shit out the front. Roman was lavish with love towards him. He’d given him as a puppy— with the name Tonka—to our son, when he turned eight. Now, he called him Party Boy in a singsong voice, while he fed him chicken necks and comically large bones on the rug. Stanley, the guard pittie Roman had named after mass murderer Stanley Graham, would watch me through the kitchen window from on top of his kennel under the phoenix palm. If I met his empty gaze, it was like what Nietzsche said about staring into the abyss, except, after a while, the abyss got used to me and thumped his tail. Slightly. Turns out the abyss enjoys a steak.

Sometimes Roman would get us hangi in covered foil trays from the shop around the corner. I doused my steaming tray in mint sauce, a childhood habit I’d picked up from Sunday hogget roasts after church with my grandparents. The vinegar cut through the gassy cabbage, sheep fat, and starched smoky sweetness of the kumara and pumpkin. And who doesn’t love stuffing? Our son was just relieved that his father had given his nearly crazy mother somewhere to live.

Near Art! Fun! Wear! was my favourite secondhand shop for its superlative Maori collection, a wakahuia obscured by the travel cots displayed outside. Inside, there were whiskey bottles shaped like Te Rauparaha and other rangatira, a genuine find. There was a pickaninny ashtray and a weird print homage to Rachel Hunter, Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, and KZ7, beside jigsaw puzzles that once assembled revealed a stern Captain Cook being greeted by happy natives. I guess these finds were pretty offensive, but I coveted them all. I love Māori tat. And Te Rauparaha whiskey was less problematic to me than a golliwog, because his heke murdered so many of our iwi in the unfair game that war became for Māori with the introduction of the musket.

Meanwhile, the local statue of Captain Cook on the port’s waterfront had been branded with the words ‘Pakeha Thief’, in a protest at Tuia 250. It was a dig at those in Tairāwhiti trying to celebrate (under the guise of commemoration) the two-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of Captain James Cook turning up in 1769 and murdering some locals with his crew, with the same poverty of imagination he used to rename their gorgeous bay. It is telling that most people in this country will have heard of Captain Cook and that there is a global scholarship industry obsessed with his voyages, when Te Maro of Ngāti Oneone, who was the first Māori to be killed by Pākehā on his own whenua, is barely known or talked about outside his own people. There were no macrons used over the two ‘a’ in the ‘Kupu Pakeha’ defacing the statue, possibly because the graffiti artist was in a hurry.

Although I fully supported the righteous vandalism, the statue is rude af. My own Kurahaupō iwi had a different story to tell about their encounter with Cook. Ngāti Kuia and Rangitāne o Wairau are far less visible within our own rohe than these mighty Ngāti Porou and Rongowhakaata iwi. Kurahaupō iwi chose to meet the Endeavour-replica flotilla in waka last year, if only to remind people who the whenua and the wai truly belongs to in Te Tau Ihu, and that, despite Te Rauparaha’s tactical decimation of us between the arrival of Cook and the signing of Te Tiriti, we are still very much alive.

Cook was more understanding than a picky, plant-based eater when my ancestors, led by Kahura, ate ten of Furneaux’s men over a grievance at Wharepunga Bay in 1777. He reminded the outraged crew they had probably insulted them. But that insight was only possible because we were equally curious about them and what was onboard their big, buxom ships. We could have killed all those honky devils, but chose not to. Since our arrival in Aotearoa from Hawaiki centuries before, fuck all other people had turned up to visit and these clumsy manuhiri had nails.

I muttered to myself and to Roman from the couch that the real raruraru with Pākehā didn’t start until we signed Te Tiriti and the settlers descended on us as a troubling mass. Cook was just the first to wedge open the gate using his silly naval flag. His impact on the whenua, apart from the immediate human tragedy, was negligible, but the legacy of his voyages to Aotearoa is immense and shattering. Roman replied to my horizontal muttering by reminding me that all my sentences began with the letter ‘I’ and that no one likes a big head, pointedly watching YouTube videos about Emmett Till, as he repeated the words ‘big head’ at me, because he didn’t want any of my trouble in Gisborne.

Still, I felt haunted by those men sleeping beside a poisonous-looking river, by the difference between the haves and have nots I tallied at the two supermarkets. I studied a woman in a silver bob, the official senior helmet of the middle class, cramming a basket with all the bougie favourites. I saw a kōtiro, about seven, counting each grocery item too carefully as it moved along the conveyor belt at Pak’nSave. From behind, a man, who I assumed was her father, watched over her with the same stern regard. I caught myself staring and looked away. It’s rude to stare anywhere, but it felt extra rude here on the coast.

One of the reasons Maori is so precious to me is because Ans Westra caught Māori men in the act of being good. And this is doubly poignant because the book was published in 1967. Over the next decade, the state accelerated its uplifts of our tamariki, almost collapsing the structures of Māori whānau by ripping tamariki from the heart of their harakeke and putting rangatahi in punitive homes. Now, gang members on television and half-broken people in print media describe being ‘interfered’ or ‘fiddled’ with as historical wards of the state. These are subtle words, when a tane uses them like this in hindsight. They manage to say so much with so little. But then Māori have this knack for subtext, maybe especially when it elides a horror.

When my Mum was studying early childhood in 1980, Betty Armstrong, her Pākehā tutor, showed her class the Ans Westra image from Maori of a man pushing a wheelbarrow surrounded by kids, including the one riding his shoulders and the other laughing from the wheelbarrow. He is smoking as he pushes the wheelbarrow, but everyone smoked then. There is another image of an older man bending down to the same level of a little girl as they both corkscrew into the twist. And, my own favourite, because it reminds me of Roman, where a younger man in a mesh singlet lets one toddler happily eat beside him, while the other has a tutu with his singlet. It reminds me of those moments when Roman played much easier than me with our son and freed up my fingers to do something useful. This is reversed in my other sentimental favourite from Maori which shows a man under a tree fiddling with what might be a blade of grass as a woman walks past him in gumboots, slinging a toddler out her front.

They are such intimate, natural images, but how did Ans Westra get so close to us? The New Zealand she arrived to in 1957 was socially segregated by geographical and political factors, into white and brown. But this was on the cusp of change, as Māori were moving from papakainga and smaller towns into the city. Ans became enamoured with a Māori family over the fence in Auckland, who were part of the new urban migration to the cities. Her Eurocentric gaze noted how free, natural, and spontaneous they seemed, compared to her own reconstituted family, and her camera started seeking us out. She moved to Wellington and found us at Ngāti Pōneke kapa-haka club meetings and became their official photographer. She would also catch the train out to Waiwhetu, the marae being built in Lower Hutt.

She saved enough money working at Rembrandt Photographic Studio on Cuba Street to buy a secondhand Volkswagen and began driving out of town on weekends to remote Māori areas. The car had just enough room to hunch her long Dutch frame into for a terrible night’s sleep. Later, she would sometimes have her children in tow, tamariki with hair like wheat, heading off with their mother for the browner parts of the map. Tall and stooped, with her camera at waist level, she would have seemed strange to Māori at first. This wasn’t the usual Pākehā behaviour for a woman. And they would invite her in, because anything could happen to her out there. And children are often curious about a camera and would have been her first point of access, I suppose, it’s canny of her really to shoot from the hip.

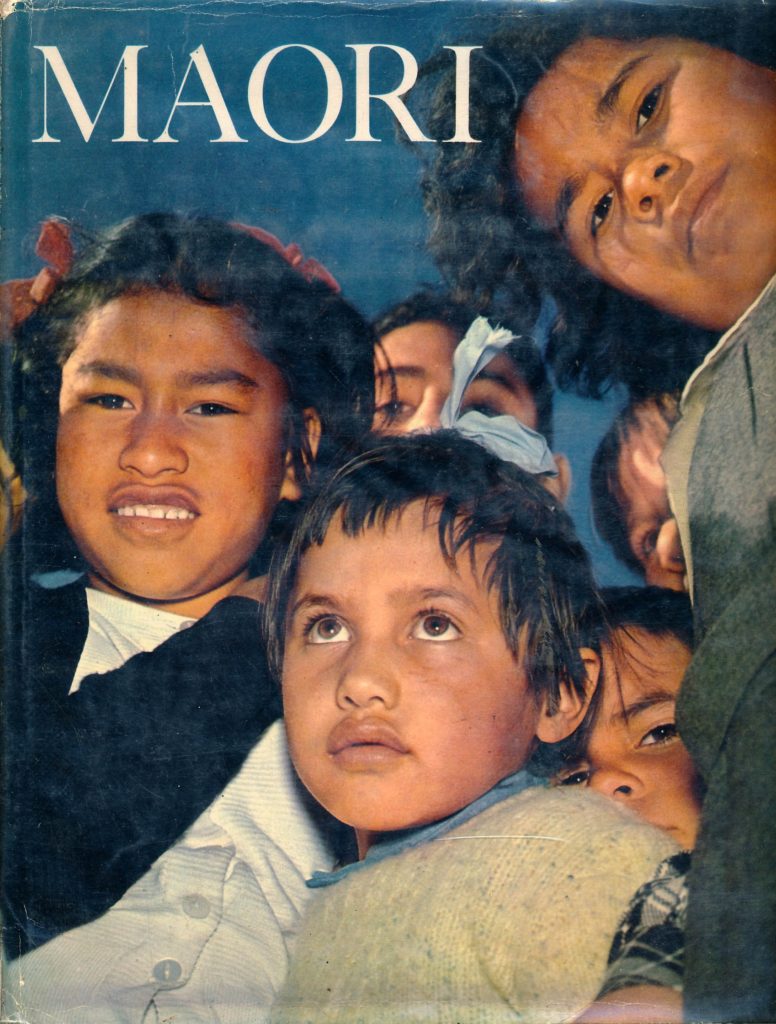

The colour dust jacket of Maori shows tamariki looking down into her lens. They are from Ruatoria, a specificity she had previously disguised in Washday at the Pa, three years before, giving them another surname, Wereta, and pretending they were from Taihape, to protect their identity, and, in doing so, added her milk to their strong, dark tea.

The Māori Women’s Welfare League met in Dunedin the year Washday was published then withheld because of their outcry against it. They scalded Ans Westra with their tea. But it wasn’t the anonymity of the whānau which disturbed them. They were more concerned that the publication of these images by the Department of Education would make Pākehā look down on us. Some more. One image showed children lighting each other’s cigarettes, but they were only copying the adults around them. The League’s agenda was aspirational. They were going to show Pākehā how to be better ladies; they were going to beat them at their own domestic game. Most of the 38,000 copies of the booklet were guillotined in the furore. This is a pretty ghastly fate for images of happy children, to chop off their heads.

Ans Westra revisited Washday in a later series of images. One of the main subjects, called Mutu in the original text, told Ans she didn’t need wallpaper or carpet in her adult whare because it reminded her of the safe, happy home she grew up in back on the coast. Her mother’s consent for them all to be photographed by Westra also seems a bit lost in the historical fuss.

To me, as a contemporary observer, it is more anthropologically frustrating that Westra changed their names and location than to present smoking children or Mutu breaking tapu by warming her feet on a stove. Tikanga tends to be a bit more flexible in private, but that image incensed the League. Yet the mother in these images is so freely intimate with her children, and this Pākehā woman was allowed to record it. The story of Westra’s perseverance with us hits me as a mother. Her pluckiness is admirable, I think, especially when she describes herself as a bit shy. I am shy too. And, like her, I am far more interested in what is happening in the neglected corners than on the main stage.

It is also why I am suspicious of her career built on images of Māori, because we have proven to be such a cheap date and Westra used her vulnerability—whether she was conscious of it or not—to engage with us, as much as any mandate for mahi from the Department of Education. And her gaze is not the same as ours, with its secret toughness underwriting the consent. Māori transcend her gaze. We are bigger than her, so it is a painful irony that Ans Westra’s images are a collective taonga we rarely possess. We animate Maori unnamed by place, person, marae, hapū, or iwi, the social circuits which form the motherboard of our being. Although I have managed to recognise some of the marae in Maori by the women doing kopikopi in the Waikato or the mana wahine energy of the ancestral pou at Hiruharama near Ruatoria. The nunnish habits at Rātana competing with the honking of the brass bands took less detective work because it was a large well-known event. Our real stories should be this noisy, they should be spilling out the sides of her frame.

Ans Westra was poor and aspirational when she ventured off in her Volkswagen in search of our arcadia. When Māori became more radicalised in the 1970s, some were critical of her shy presence in our world. She argued she earned about the same then as a cleaner for her art. It is too humble a claim, when Ans Westra is a living legend and reciprocity quietly demands she polish more than her own lens.

The man in the mesh singlet appears again in Maori. He stands at the sink so you can only recognise him from the back. Two women and some kids sit at the stuffed table in the close kitchen. The children are working happy bones. They appear in other images of Maori and I recognise one by matching the cuffs of his pyjama sleeves. He is why Ans Westra got so close to us. But it is his turned back at the sink which suggests something to me too. I wonder if they are a whānau from the coast from the angle of the sun hitting the door and the open face of the boy, but this answer is held mostly in the archives.

I can’t reproduce Ans Westra’s images here without asking for her permission and I am reluctant to ask because of this history of her ‘taking’ our photos. It has left me in something of a bind, but maybe I prefer an unsolved puzzle? Roman wouldn’t let me near the closed Coastie Facebook groups, where they were clucking over who was who in some of her images. He is guarded because my nosiness is embarrassing to him. There is also the danger I would discover that he was making up this story of invested online aunties to distract me from my sorrow, which was stinking up his house.

What I remember most about being in labour with our son is this sudden involuntary turn into a wild animal, and having to surrender to being subject to my body’s will. There is no getting out of it now, I thought, as Roman fussed at me to hang up my towel and I marvelled at the hospital’s endless supply of gushing hot water filling the bath. The water was my only relief from the pain because the gas made me throw up the Big Mac and McChicken I’d had for lunch before my induction, and there was no way I was staying still for a needle going into my spine.

When my son was a baby, I used to sing him ‘Summertime’, ‘The Girl from Ipanema’, and this song from primary school in Foxton Beach, ‘When the Red, Red Robin Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin’ Along’. The lyrics of the latter advise the listener to ‘Wake up! Wake up! You sleepyhead!’ It was a contradictory song to sing as a lullaby, but he seemed to like it. Its forced cheeriness was reassuring to me as a young, new mother feeling the walls of the house close in on my isolation.

Funny, I guess, that two of my son’s favourite songs have the phrase ‘wake up, wake up’ in them. Aaradhna’s song ‘Wake Up’ reminds me of when we used to live in Aramoana. He thrashed it from the sleepout beside my annuals in the sweet courtyard garden. If I didn’t water my flowers, they would sizzle off in the sandy soil like the mist that hung as a white woolly beard over the cliff in the mornings. At last, a memory with a bearable echo.

The other song is Mad Season’s slower, droning ‘Wake Up’. Roman played this grunge dirge when my son was fifteen and he brought it to my house with its view of the harbour and the monkey-puzzle trees. ‘Wake Up’ was the song on repeat in the weeks before the tornado and my new silver car, but I have fewer regrets now about not setting the house I left on fire. Still, I can’t hear it without feeling for a warning which pulls much deeper than a siren.

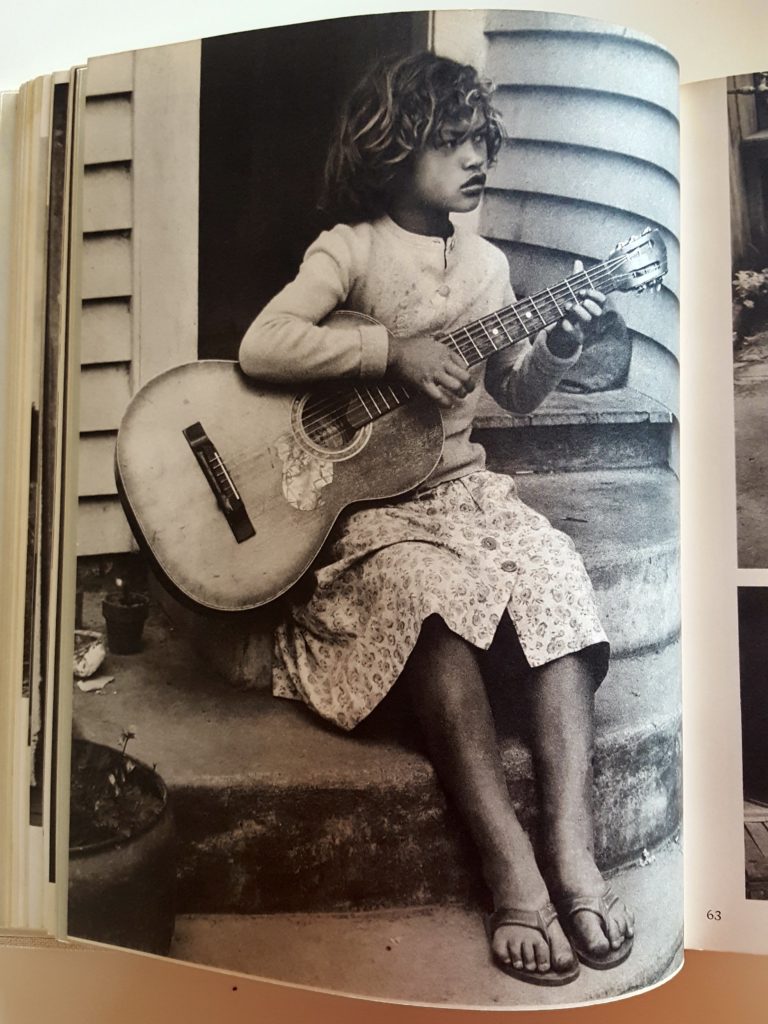

But this sound is the thing I want to write into the images in Maori, as much as solving the mystery of who the man in the mesh singlet is. Roman is not the right name for him; he would hate it. If I go further, and follow the music around the path down the side of the house there is a Māori girl on the back steps by the door. She is sitting there with a guitar, wearing jandals under the polite skirt tucked over her knees. She is playing the be-positive chord of D, and the kurī are gentler lions. They are ghosts the camera does not see.

—Talia Marshall

Talia Marshall (Ngāti Kuia/Rangitāne ō Wairau/Ngāti Rārua/Ngāti Takihiku) is a Dunedin-based writer. Her first collection of poetry is forthcoming from Kilmog Press. In 2020, she was the inaugural emerging Māori writer in residence at the International Institute of Modern Letters. Her project was to write about Maori by Ans Westra and James Ritchie, to try to locate some of the people in the book, and to develop her own book-length photo essay as a response. During her first week at the Institute, Covid infections started popping up all over Aotearoa, so she returned to Dunedin without the book, because she could see she was going to get stuck in Wellington with no stable accommodation. By the next week, she was in lockdown, and it was impossible to start taking photos of contemporary Māori or to begin locating subjects of the book without permission from Ans Westra to reproduce the images on social media. These are things she would still like to do, and this essay is a response to having such bad luck—although the book is with her again.

Born in 1936 in the Netherlands, Ans Westra emigrated to New Zealand in 1957. In the early 1960s, she began extensively photographing Māori people. Much of her work was published by the Department of Māori Affairs in its magazine Te Ao Hou/The New World and by the School Publications Branch of the Department of Education. In 1964, her photo-book Washday at the Pa was distributed to primary schools, then withdrawn by the Minister of Education at the request of the Maori Women’s Welfare League. In 1967, Westra’s Maori was published, with a text by James Ritchie. The monograph Handboek: Ans Westra Photographs was published in 2004 and the documentary Ans Westra: Private Journeys/Public Thoughts was released in 2006. Westra became a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit in 1998 and an Arts Foundation of New Zealand Icon in 2007. She lives in Wellington, where she is represented by Suite Gallery.