ARTISTS Derrick Cherrie, Andrew Drummond, Jacqueline Fraser, Terence Handscomb, Paul Hartigan, John Hurrell, Robert McLeod, Maria Olsen, John Reynolds, Pauline Rhodes, Peter Roche, Victoria Sheppard, Erica Sowman, Merlyn Tweedie, Ruth Watson, Ivan Zagni CURATOR Gregory Burke SPONSORS Athfield Architects, Craig Moller Architects, Stephenson and Turner New Zealand, Warren and Mahoney Architects PUBLICATION essays Gregory Burke, Tony Green, Christina Barton

Drawing Analogies—Gregory Burke's first major show as the Gallery's first curator—showcases artists who explore and extend notions of drawing. Burke rejects the idea that drawing is simply preparatory for—or subsidiary to—painting and sculpture. ‘New Zealand art educators have taught students to think of drawing as preliminary to resolving ideas in other media’, he complains to the Dominion Post. Works in the show are, use, or reference drawing in different ways. The show features established artists, including Andrew Drummond, Rob McLeod, and Maria Olsen, alongside younger, emerging ones. Ruth Watson, for instance, had only had her first solo show seven months earlier.

On the opening night, Auckland composer Ivan Zagni plays amplified acoustic guitar on the Library lawn using a weather map as a score. Drawing and mapping are linked in two other artists’ works. Ruth Watson’s World Map looks antique, but contains modern imagery and is made using modern processes—collaged photocopies. For her, maps are not objective representations of the world, but psychological and political ‘projections’, riddled with metaphors and analogies. John Hurrell projects the outlines of figures from hip European transavantgarde paintings over maps of Christchurch, then paints out in black everything other than the roads touched by the outlines. Paradoxically, his spiky expressive-looking images are produced by the least expressive process. Translating the mythic though the mundane, he sees them as a critique of national identity.

Derrick Cherrie’s installation Primary Structures combines drawing, painting, and sculpture in a play of translations and iterations. He made a small scribbly ‘expressive’ drawing suggesting something small (building-blocks) or large (a classical ruin). He enlarged it on a photocopier, then via an overhead projector, traced the enlarged, degraded lines in paint. The resulting painting carries qualities of the original sketch, the degradations of the photocopy process, and its transcription using the paintbrush. Cherrie’s accompanying sculptures combine the same building-block forms in arrangements, one more abstract, one more figurative. He covers them in embossed satin wallpaper.

Andrew Drummond and Peter Roche also place pictorial and sculptural elements in conversation. Drummond is a primitivist. His big pencil drawings picture a basic boat on a river and feature handprints, recalling cave paintings. His woven willow sculpture suggests both an upturned canoe and a hut. Roche’s works—conveniently titled Kinetic Drawings—celebrate machine energy.

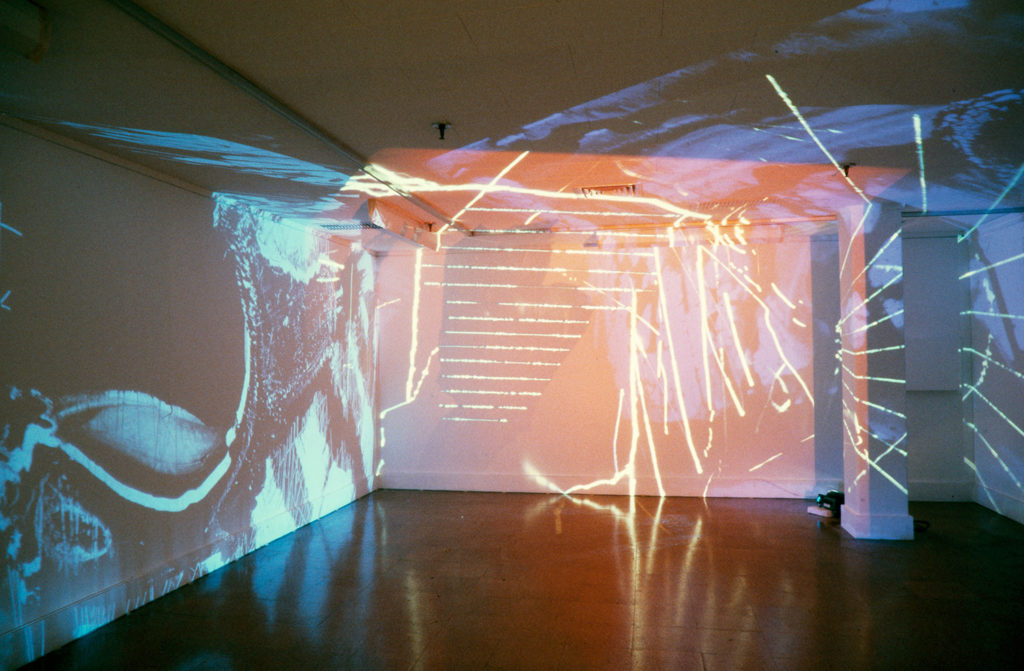

Pauline Rhodes, Jacqueline Fraser, and Victoria Sheppard make ‘drawings in space’. Rhodes presents a freestanding 'extensum' of concertinaed plywood sheets, amended with cut-out apertures; Fraser ties-and-suspends and cuts-and-scatters raffia; Sheppard projects slides of scratchy coloured lines across the gallery walls, ‘drawing’ with the projector.

Feminism and gender are key reference points. Drawn and painted on polyester film, Terrence Handscomb's charts combine diverse marks and inscriptions, including references to the algebra of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. While his inscriptions may be philosophically obscure, their titles—Discursive Phallus and Pastoral Anus—are enticingly obscene. In the show, these heavy-hitter theory works sit opposite Erica Sowman's more old-fashioned feminist ones, including Opening Flower series, with its floral vagina forms rendered on tissue paper. She explains: ‘The flower opening, Opening Flower, the Fire Flower, unfolding layer after layer her petals, revealing her centre, and creating her definitive shape and identity as the flower.’ Handscomb’s work has more in common with Merylyn Tweedie's grungy video, A Narrative that Provided the Measure of Desire, showing words scribbled over a fragmented bedroom scene with a soundtrack of garbled female voices and childish babbling. It’s an attempt to represent that which can't be represented—woman.

The show also features large abstract works that put a new spin on expressive mark making. John Reynolds makes his marks on marbled paper, McLeod on large folded building-paper forms, and Paul Hartigan in neon.

Drawing Analogies is complemented by a series of seminars and workshops, along with an education programme designed by new Education curator, Jill McIntosh. One of the forums, Gender, Sign, and Drawing, includes Handscomb, Sowman, and Julia Morison. A publication documenting the show is published.

Critics draw their own analogies, most favourable. Evening Post critic Ian Wedde calls it the best show of 1987. 'Despite the modest presence of the curatorial hand, this is likely to be a benchmark exhibition.’ Lita Barrie reviews it twice. In National Business Review she says, 'The significance of Drawing Analogies has been to demonstrate how drawing has entered the “expanded field”. It has drawn the Wellington City Art Gallery into the field of more thoughtful curatorship.’ In her Art New Zealand essay, she concludes, ‘Drawing Analogies has been the most visually pleasurable and sensitively curated exhibition of New Zealand art I have attended.’ But it can’t be unanimous. In the Listener, Lindsey Bridget Shaw says, ‘What then is the new idea of drawing that we should take away from this show? That is the problem: we are never told. Questioning old concepts is easy. Suggesting alternatives takes a lot of careful thought.’

1987"

alt="">

1987"

alt="">

1987" alt="">

1987" alt="">