ARTISTS Mary-Louise Browne, John Buchanan, Derrick Cherrie, Philip Dadson, Department of Survey and Land Information, Andrew Drummond, Robert Ellis, William Fox, Charles Heaphy, John Hurrell, John Kinder, Tom Kreisler, Ralph Paine, Julius von Haast, Ruth Watson, Wiremu Wi Hongi CURATOR Wystan Curnow ORGANISER Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth OTHER VENUES Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, April – May 1989; Waikato Museum of Art and History, Hamilton, 2 August–17 September 1989; Manawatu Art Gallery, Palmerston North, 5 October–3 December 1989; Suter Art Gallery, Nelson, 6 April–29 April 1990; Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch, 10 May–24 June 1990; Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 5 July–19 August 1990; Auckland Art Gallery, 6 September–21 October 1990 SPONSORS New Zealand Art Gallery Directors Council, QEII Arts Council PUBLICATION essay Wystan Curnow

Mapping land is a step in taking possession of it; it’s political. Coinciding with New Zealand's 1990 celebrations—marking 150 years since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi—Putting the Land on the Map explores the cultural connotations of maps and mapmaking in New Zealand art since first European contact. In the catalogue, curator Wystan Curnow explains, 'Putting the Land on the Map is an exhibition of maps and works of art which resemble, incorporate, or play the part of maps.' He then turns the title on its head: 'Or, if you like, have it the other way: putting the map on the land. The exhibition explores the nature and ramifications of that act.' The show is organised and toured by the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, whose Director Cheryll Sotheran tells the Daily News, 'I cannot think of a similar exhibition ever being held in New Zealand. It is one of the most challenging shows to ever be mounted in this country.'

We are used to looking at landscape images as if we are looking through a window onto reality. Maps, on the other hand, seem explicitly coded—opaque with words and numbers, scales and grids, signs and symbols. In focusing on their conventionality, Curnow offers an alternative 'landscape' show, one that exemplifies the postmodern turn with its interest in signs and language. Putting the Land on the Map is one of a series of ‘theme shows’ that distinguish the late 1980s, early 1990s.

The show is organised into three sections. 'Nineteenth-Century Artists and the Map' features colonial-period works from the Hocken Library and Alexander Turnbull Library collections. 'Mapping Pouerua' covers Māori concepts of territoriality and route making, contrasting Māori approaches with those of early Pakeha artists and cartographers. The 'Contemporary Artists and the Map' section features mid-career and young artists, from Robert Ellis to Ruth Watson.

Nineteenth-century colonial painters were often employed by colonising enterprises, such as the New Zealand Company. The work was not primarily seen as art, but as topographical record. Charles Heaphy, Julius von Haast, and William Fox were respectively surveyor, geologist, and explorer. Their brief was to survey land for development or exploitation, and a proprietorial bias was built into their views. Curnow writes in his catalogue essay, 'The New Zealand Company stamp smack in the sky of Fox's Bird's Eye View, Waitohi needs no explaining away, rather it's to be regarded as a supplementary signature, one which seeks and finds its coordinates in works and maps among which it now hangs.'

Focusing on the Northland area, ‘Mapping Pouerua’ uses maps and artworks to explore the ways Māori and Europeans made their marks and claims on the land. It includesan oral map of Northland, a wānanga by Wiremu Wi Hongi that relates legends establishing the foundation of Nga Puhi as a tribe. This section also includes a map of Whanganui River map made by John T. Stewart in 1903 for European tourists. It’s unusual in including the Māori names for every detail of the river's course; at this time map makers had no qualms in replacing Māori placenames with European ones. The oral tradition of the Māori was replaced by Pakeha maps, made by surveying teams.

The largest part of the show is works by contemporary New Zealand artists, which explore maps as subject, metaphor, and material.

Derrick Cherrie’s sculpture The Navigator (1987) is a enigmatic centrepiece. A giant, anonymous, heroic figure balances two chairs against its back. The figure seems to be striding forward, but—were it to do so—the chairs would fall. Everything is balanced in precarious equilibrium. The surfaces of the figure and the chairs are papered with world maps.

John Hurrell transposes famous art images onto New Zealand streetmaps, playing on the difference between centre and periphery. Where outlines in the quoted image cross streets in the maps, he retains the whole street; the rest he paints black. The resulting spiky reiterations recall the outline auras found in Kirlian photos. The show includes works based on paintings by German expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and on a pop painting by Roy Lichtenstein.

Philip Dadson also scrambles here and there. His 1971 film Earthworks collates sounds and images recorded in fifteen locations across the globe during the equinox, when day and night are of equal length.

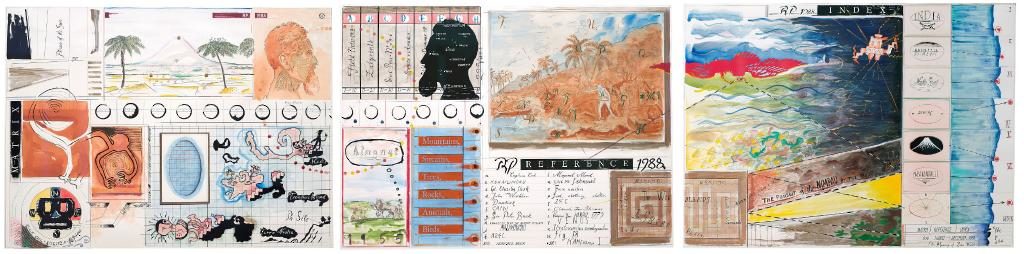

The relationship between maps and colonisation is explicit in Robert Ellis’s paintings of Rakaumangamanga—a mountain of spiritual and mythological significance for local Māori (his wife’s people). These works scramble and clash Māori and Pakeha understandings, as the mountain is overwritten with competing cartographic signs and Māori symbols. Ralph Paine's triptych Matrix, Reference, Index (1988) is dedicated to John Webber, the artist on Cook's third and final voyage. It quotes Webber's depiction of Cook's death in Hawaii, while piling up other references to anthropology, colonisation, and cartography.

There's a vein of romanticism in the show. Ruth Watson is concerned with the projection of inner human psychology onto the external world. Her faux-antique Map of the World (1987) is based on a sixteenth-century map of the southern hemisphere by the German globemaker Johannes Schoner. Watson incorporates references to the body, street maps, and molecular diagrams. Sculptor Andrew Drummond’s Braided Rivers installations juxtapose sculpture and drawing elements. The drawings feature his own silhouette or shadow combined with images of braided rivers of Otago, where he has lived. The sculptures are primitive slate shelters and a boat shape bound-willow form. Drummond says the works had their ‘genesis somewhere between the river and the body’.

At each venue on the tour, Mary-Louse Browne installs a marble plaque bearing the city’s motto and the combined distance of all the city’s streets named after women, pointing out that sexual equality is miles away. Wellington's Milestone reads, 'Supreme by Position, 12 Miles, 1990’.

Some works are less serious. Tom Kreisler's jokey paintings riff on the concept of weather maps. In Mostly Moist on the West Coast (1988), it 'rains cats and dogs'.

In his Dominion Post review, Rob Taylor says, 'The exhibition theme goes beyond local issues of land mapped in the process of territorial possession to cover curatorial favourites who have coincidentally made use of maps.' Artists like Andrew Drummond, Ruth Watson, John Hurrell, and Tom Kreisler have all been seen before in group or solo shows at City Gallery. Taylor concludes, 'The exhibition attempts to remain true to nifty curatorial practice while also seeking to confront a truth for these times. The problem of blending these two concerns extends to the catalogue, a loose assemblage of scholarly fragments with hipster undertones, and poorly reproduced exhibits.'

Putting the Land on the Map features an extensive public programme. A video of Curnow introducing the show is available on request. There are also slide shows on art and mapping in New Zealand and on the history of mapmaking. The children and schools programme includes a kite-making and 'Mapping Games' workshops. A surveyor’s theodolite is installed in the resource area.